By Connor O'Keeffe, Mises Institute | February 14, 2024

The new year started out on a painful note for autoworkers building electric vehicles (EVs). In the last month, thousands of workers have been laid off from General Motors (GM) and Ford plants in Michigan.

Most workers involved were, or were slated to be, working on electric versions of each brand’s signature trucks—the Chevy Silverado EV and Ford F-150 Lightning. The latter has been available for purchase since 2022, with the Silverado EV set to debut this year. Yet both have run into a problem: consumers don’t want them.

More specifically, consumers don’t want as many of these trucks as Ford and GM are currently producing. On its face, this might appear like a classic case of entrepreneurial error. But there’s more to the story because the production level of EVs, in recent years, has been defined more by politics than any actual attempt to anticipate consumer interest. And, as recent weeks have shown, the big losers in this politicized production process are the workers.

When we talk about the economy, it’s always important to remember that we’re talking about a process, not a state of being. Specifically, it’s a process for producing goods and services that satisfy the needs and wants of the end consumers. Every part of every line of production—from the drafting of children’s books to the manufacturing of shipyard cranes—is a means toward that eventual end.

But government often comes in and spurs new production projects without any regard for the wants and needs of end consumers. Such is the case with these electric trucks.

Take the GM plant from above in Michigan’s Orion Township, for example. The plant has been around for decades, but two years ago, Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer used hundreds of millions of tax dollars’ worth of grants and other political favors to goad GM into expanding EV production at the site.

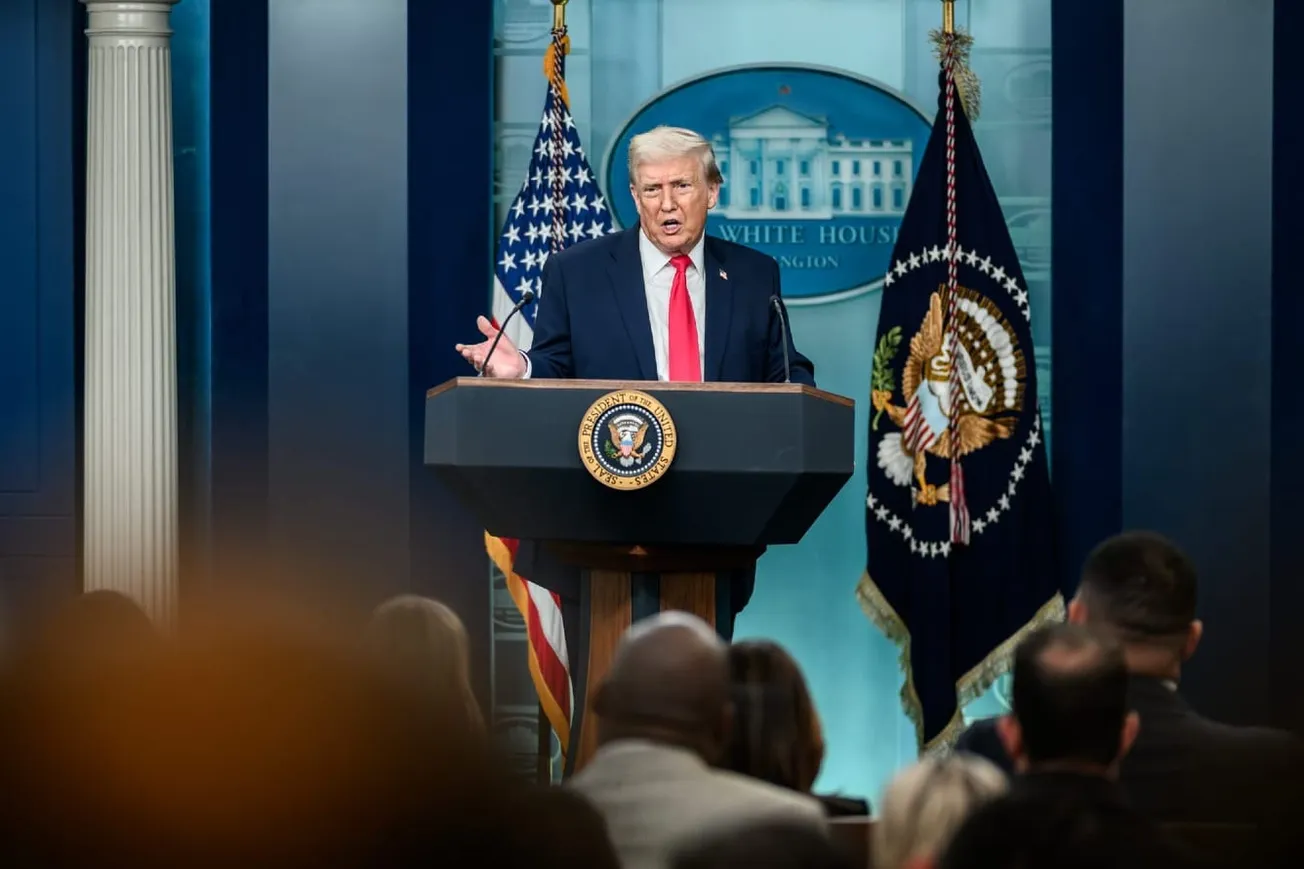

At a triumphant press conference in early 2022, the Democratic governor celebrated the thousands of future jobs she had helped secure while making Michigan a home for the “electric vehicle future.”

The optics of creating jobs while saving the world from climate change probably helped Governor Whitmer as she ran and won her reelection campaign later that year. But eventually, GM could no longer ignore the fact that the governor gulled them into making a bad investment. These new jobs and capital investments were going toward the production of cars that wouldn’t sell.

So, last December, GM laid off nearly a thousand workers from the Orion Assembly plant. In January, Ford followed suit and announced it would start laying off fourteen hundred workers in Dearborn, Michigan, in April. Both companies have also announced delays and scale backs of previously planned EV investments.

While this is one case of government politicizing the production process, there also are many others. What Whitmer did mirrors the policies of many of her fellow governors across the country, and moreover, it resembles President Joe Biden’s economic agenda.

It should go without saying that this is bad for workers. These politicians are leading these workers into jobs where they produce things people don’t even want, thereby dooming them to continually insecure employment and all the instability that brings to their lives. On top of that, these projects also draw workers and capital away from the production of other, more valued goods, making everyone worse off.

Entrepreneurs and company executives must be allowed to produce what consumers actually want and need. The government shouldn’t stand in their way with legislation and regulation and shouldn’t lead them away from doing so with subsidies and political favors.

It’s not the fault of Michigan autoworkers that they were essentially tricked into ill-fated jobs. That blame belongs to their governor.

Connor O’Keeffe produces media and content at the Mises Institute. He has a master's in economics and a bachelor's in geology.

Original article link