In recent years, the U.S. has suffered recurring banking crises almost like clockwork. Indeed, about every 10 years or so we seem to go through another financial panic, only to be followed by a spate of bad regulations passed to ensure “it won’t happen again.” But it always does. So how do we end this cycle?

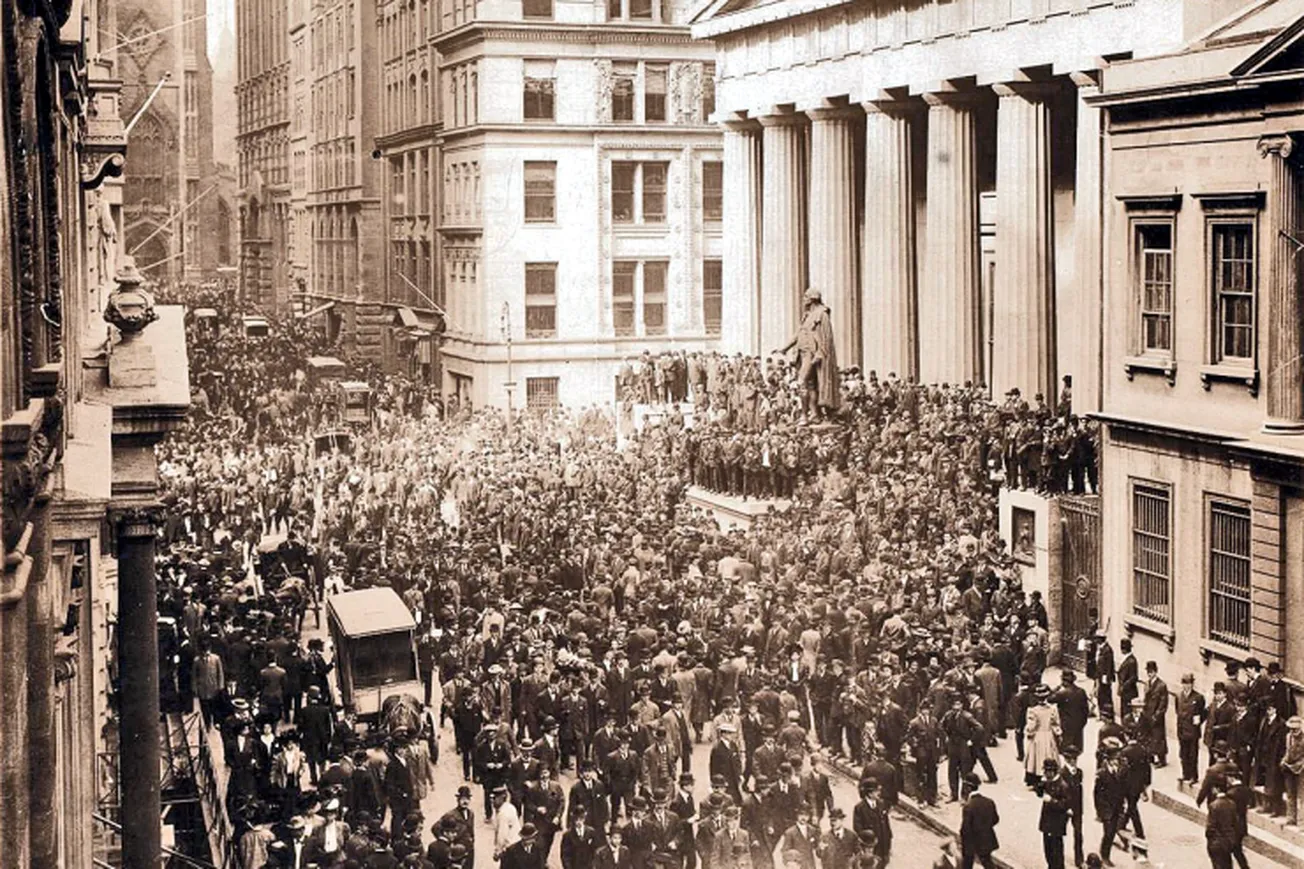

U.S. banking disasters plagued the late 20th century and early 21st century. But of course they go back long before even that, to 1907 and 1929, as two examples.

More recently, there was the 1980s and ’90s savings and loan crisis, the 1998 collapse of Long-Term Capital Management and global crisis, the 2007 financial crisis (which also became a global bank crisis), and, now, the Silicon Valley Bank collapse, which has already hit both smaller U.S. banks and foreign banks hard, and still remains a threat to the stability of the global financial system.

But the big questions are: Why do these financial crises keep happening? And what can be done to stop them?

The first answer is easy: They keep happening because of the Fed. Not only has the Fed done a poor job of overseeing the banks that make up its national system, but every one of the financial crises of the last 30 years or so (and even further back) was preceded by major interest rate hikes by the Fed.

In the 1980s, it was Paul Volcker’s rate hikes made to kill off the 1970s inflation bomb that did the trick. In the 1990s, it was Fed chief Alan Greenspan’s concern about “irrational exuberance” in the booming dot-com stock market that sent rates higher.

As Investopedia put it: “The easy money policies of the American central bank were meant to generate full employment by the early 1970s. Unfortunately, they also resulted in high inflation.” It took Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts, two rounds of huge Fed interest rate hikes, followed by two deep recessions, to conquer the ’70s inflation.

In the 2000s, easy money fueled a record housing boom that lasted from roughly 2000 to 2005. It was aided by banks making loans to questionable borrowers while raising huge sums of money with mortgage-backed securities. When inflation began rising rapidly, hitting 4.1% in 2007, the Fed jacked up interest rates from 1% in 2004 to 5.25% in early 2007.

The Fed’s rapid rate hikes responding to inflation almost sank the financial system, as bank and financial investment companies’ balance sheets groaned under huge losses.

Out of this came the notorious Dodd-Frank financial regulations, which imposed literally tens of thousands of pages of new regulations on banks and financial intermediaries both large and small, and created a whole new rank of privileged mega-banks (Systemically Important Financial Institutions, or SIFIs) that were deemed “too big to fail.”

Does all this sound familiar? It should.

Our own easy-money policies of the last few years that were imposed to keep the economy from crashing in 2020 as the COVID pandemic began have set off inflation once again. That includes the Biden administration’s $6 trillion “stimulus,” which did little to help an economy that was already recovering, and instead turned into a grab bag of spending goodies for favored Democratic constituencies.

Meanwhile, the Fed’s return to zero percent interest rates, quantitative easing and uncontrolled money printing added fuel to the already roaring inflationary fire.

Annual inflation peaked at 9.1% in June of last year, a 40-year high, despite the Fed repeatedly suggesting rising inflation was merely “transitory.” In response to the price surge, the Fed raised interest rates from basically zero to 5% — roughly the same rise in rates that set off the 2007 financial crisis.

Which brings us to today. On Wednesday, the Fed raised rates another quarter-point. As a reminder, as CNBC helpfully tells us, “A wide range of consumer finances — from mortgages and credit cards to student loans, auto loans and savings — will be affected by the rate increase.”

But that’s just one part of the equation. What about the banks?

With the Fed hiking rates again and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen saying there will be no “blanket insurance” for all bank deposits, the crisis that began on March 10 with an old-fashioned run on the deposits of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and a handful of others could get worse before it gets better.

We’re already hearing calls for “more regulation.” But as we’ve seen, “more regulation” isn’t the answer. More regulation has led to a steep decline in the banking industry, with the number of FDIC-insured banks shrinking by 48%, from 8,315 in 2000 to 4,236 in 2021. But is it safer?

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and other Dems want the Fed to crack down on “big banks,” which are already regulated to the hilt. Other bills are in the works.

By far the most reasonable idea we’ve heard for ending the scourge of bank crises, and the disastrous policy responses they often trigger, comes from Hoover Institution senior fellow and economist John Cochrane.

SVB, Cochrane notes, did what many banks (foolishly) do: It took short-term deposits from customers, and made long-term investments in “safe” Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, along with some risky tech bets. When interest rates rose, the underlying values of those assets plunged. Its balance sheet bleeding red, the bank had to desperately raise capital. Panicked depositors, many with millions of dollars in uninsured deposits, pulled their money out. SVB collapsed.

Cochrane’s solution? Make banks fund their long-term investments with long-term financial sources, and by issuing more stock. Put short-term deposits into interest-yielding reserves held by the Fed, and in short-term Treasury investments. Problem fixed. It’s pure Occam’s Razor.

As he notes, with such a system, “runs would end forever as there would always be money to satisfy any depositor.” No need for a massive new unworkable, and costly, regulatory regime. Sometimes the simplest solutions are the best.

— Written by the I&I Editorial Board