By Ryan McMaken, Mises Wire | December 16, 2025

The Bureau of Labor Statistics finally released its November report today—after a nearly ten-day delay—and the latest data shows that the employment situation in America continues to slowly worsen.

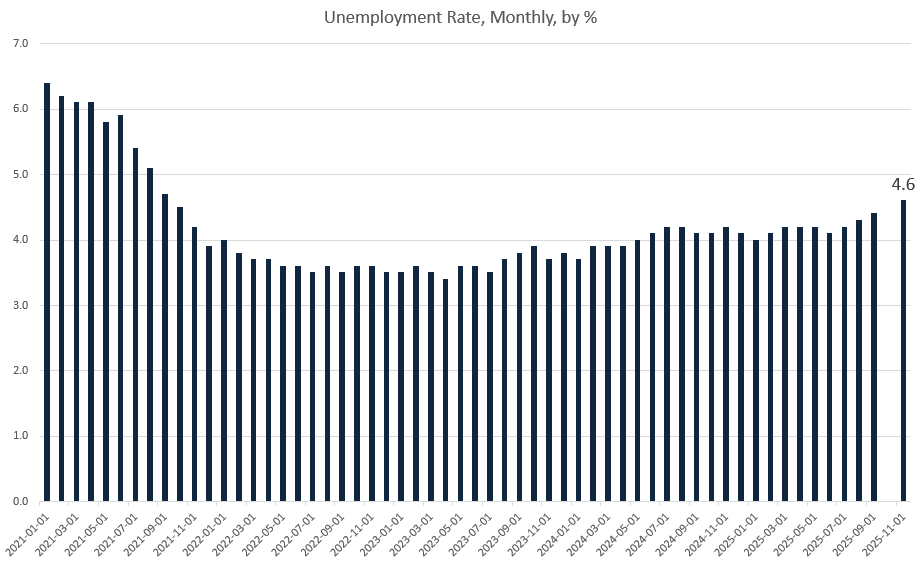

During November, the unemployment rate increased to a fifty-month high of 4.6 percent even though total payrolls rose by 64,000 from October to November. Overall, November’s report showed lackluster payroll growth fueled by rising numbers in part time employment.

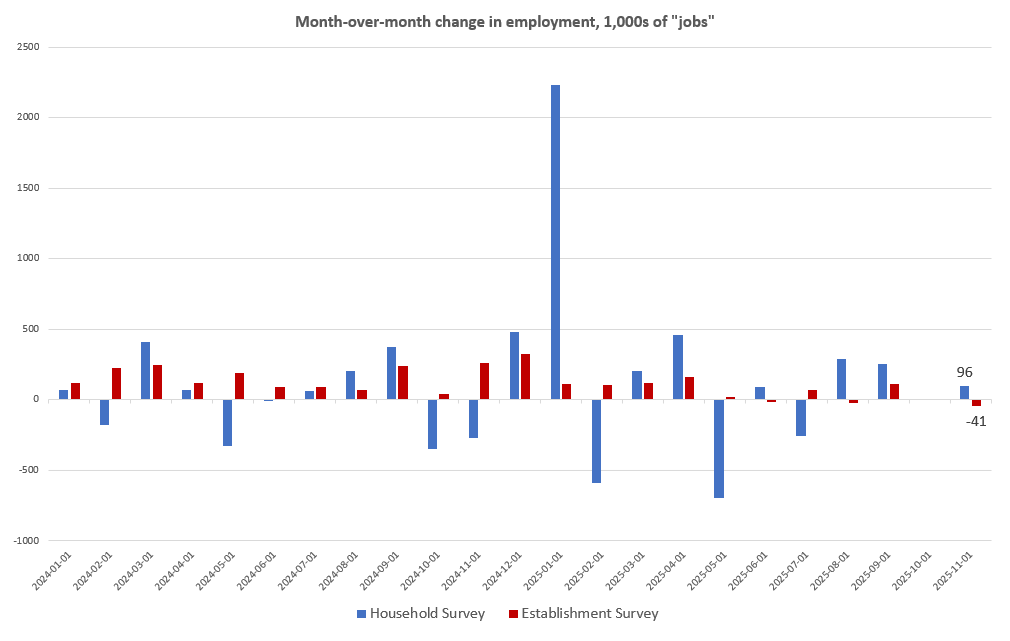

Although the BLS is apparently back on track with its November report, following the partial federal shutdown, some key sections of the October report—especially from the household survey—have not been calculated or published. So, month-to-month comparisons are difficult for the October-November period. Instead, much of what I look at here will be comparisons between September and November, to allow for comparisons between the establishment survey and the payroll survey.

From September to November, establishment-survey employment decreased by 41,000 jobs, although total employed persons, measured via the household survey, rose by 96,000. (November totals below are the two-month change from September to November):

Since April 2029, though, neither household employment nor payrolls have changed much. For example, in April, the BLS reported total household employment at 163.9 million persons. In November, the total was only 163.7 million. Similarly, for total establishment-survey jobs, the total in April was 159.4 million jobs. The total in November had risen to only 159.5 million, rising only 119,000 jobs in seven months.

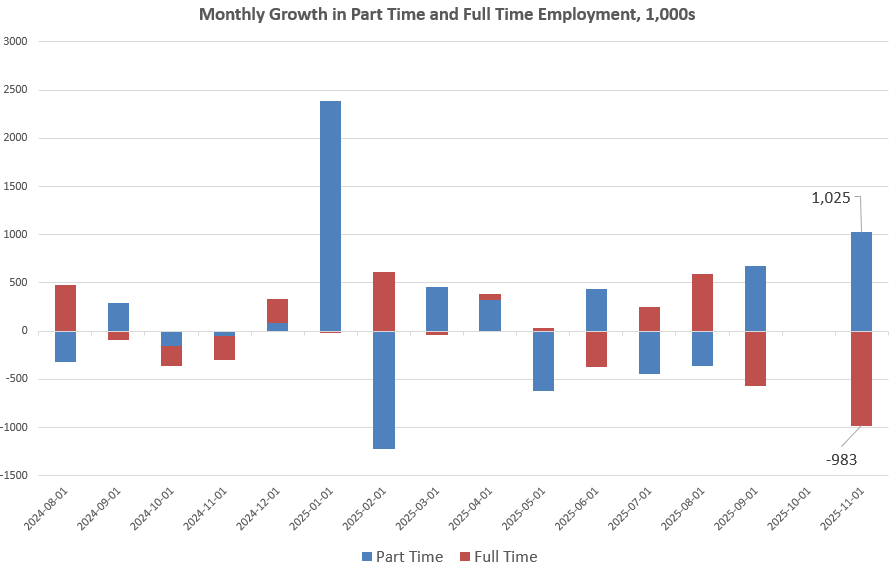

Meanwhile, the household survey in November showed a surge in part-time employment, suggesting that the jobs gains we do see are largely due to part time employment. For example, from September to November, full time employment fell by 983,000. That’s one of the largest drops we’ve ever seen outside a recession. Moreover, the total number of part-time positions surged by 1.03 million, one of the biggest gains recorded. (November totals below are the two-month change from September to November):

The total number of workers taking on part time work for economic reasons rose to the highest level since 2021, surging to 5.5 million workers.

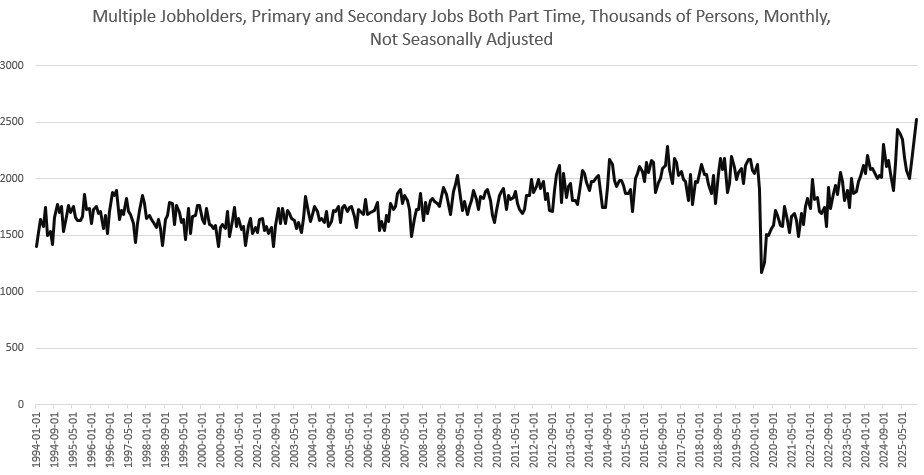

Moreover, the total number of multiple jobholders (with primary and secondary jobs being both part time) rose to the highest level recorded in more than thirty years, rising to 2.5 million workers.

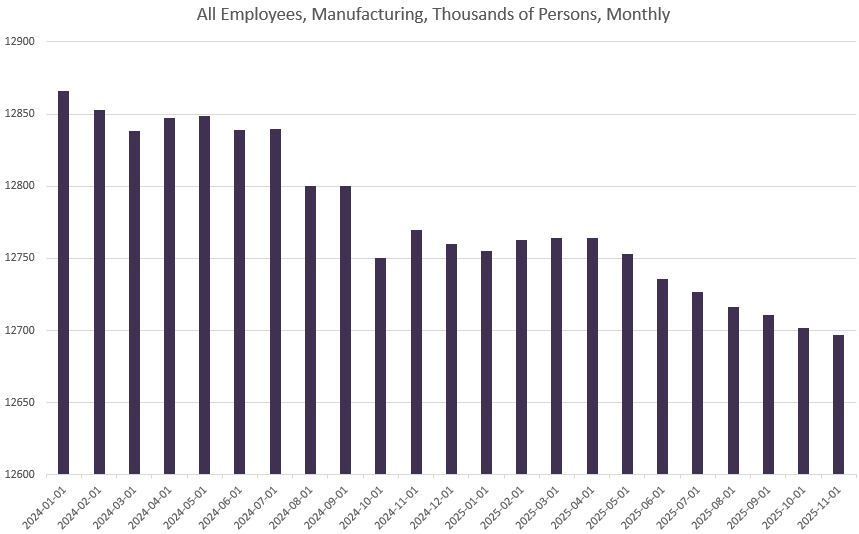

The total number of manufacturing jobs has now fallen for seven months in a row:

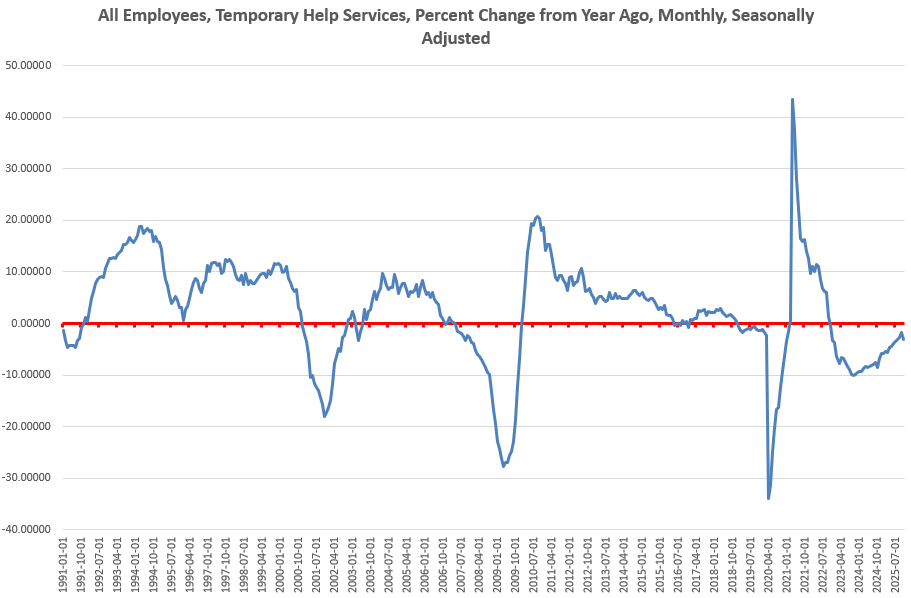

Meanwhile, temporary jobs moved deeper into negative territory (measured year over year.) This measure, when negative for three or more months in a row, has always coincided with a recession over the past 35 years.

One might say that the only real bright spot in this jobs report was the month-to-month increase in payroll employment. Yet, the report of the payroll gain from October to November comes out mere days after Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, at the December FOMC press conference, cautioned the public against putting much stock in the reported payrolls totals. According to Powell, employment is “cooling” even faster than the reported headline data in recent months suggests:

Unemployment is now up 3/10 from June through September. Payroll jobs averaging 40,000 per month since April. We think there’s an overstatement in these numbers by about 60,000. So that would be negative 20,000 per month. And, also, just to point out one other thing, surveys of households and businesses both showed declining supply and demand for workers, so I think you can say that the labor market has continued to cool gradually, maybe just a touch more gradually than we thought.

Naturally, it’s unclear if November’s count will require sizable revisions as have total job counts in other recent months, but as Powell noted, overall initial counts have been overly optimistic for months.

These disappointing jobs numbers are also reflected in private-sector employment statistics which have been the subject of more attention in recent months thanks to the federal shutdown. For example, the November report from ADP showed a 32,000 drop in private sector employment for the month. The situation for small employers was even worse, and the overall drop in the private sector was driven by falling employment in firms with fewer than 50 workers. Small businesses are more immediately sensitive to changes in economic conditions, and this may be a leading indicator of where the job market is heading.

The Rovelio Labs report on total employment, which includes government employment, showed an overall drop of 9,000 jobs in November, which according to the report authors was “predominantly driven by employment losses in the retail trade and manufacturing sectors.”

Although the Fed lacked employment data for October and November during its most recent FOMC policy meeting, the Fed was likely pushing its new policies while assuming more soft employment data. The latest data from the BLS further helps the Fed, politically speaking, in its efforts to justify further cuts to the target policy interest rate even though price inflation measures remain near three percent, and are not—as the Fed has repeatedly insisted—hurrying back to the stated two-percent inflation target.

Rather, it appears now that the Fed is still trying to engineer a “soft landing” with repeated cuts to the target policy rate, and rely on a softening of economic conditions to keep price inflation from spiraling back to 40-year highs like we saw in 2022. This might have already occurred were economic conditions more robust right now.

With such weak employment growth, however, weakening demand from workers puts downward pressure on prices, and gives the appearance that the Fed’s monetary policy is bringing price inflation under control.

Signs of increasingly weak demand are found in several places, although not in retail sales which continue to benefit from high-income spenders and from the continued use of consumer credit, including buy-now-pay-later services. For example, BNPL services have surged in recent years with the rise of apps like Afterpay and Klarna. This has helped prop up retail sales, and a November study from the Harvard Business Review states:

We found that BNPL adoption led to immediate and substantial increases in spending. Consumers who adopted BNPL were more likely to purchase, with purchase likelihood increasing from 17% to 26%. Furthermore, when adopting consumers made purchases, their basket sizes were 10% larger on average than they were before the introduction of BNPL. Remarkably, these increases in spending were not short-lived: They persisted for close to six months, showing that BNPL drives lasting gains rather than short-term spikes in consumer spending.

Who is most affected? Our analysis suggests that the impact of BNPL is greater for “financially constrained shoppers.”

BNPL is a substantial portion of overall spending. Although retailers reported record spending on the Black Friday-Cyber Monday period this year, over nine percent of that spending was financed by BNPL.

Consumers who use BNPL, however, tend to miss payments more often than consumers who use more traditional funds for consumer spending. This reflects an overall worsening in the credit situation which can been seen in rising delinquencies for credit cards and auto loans, especially among lower income consumers.

Other indicators that point to bad news for the job market include bankruptcies at a 15 year high, foreclosures up for the ninth straight month, and initial unemployment claims rising in early December by the largest total since 2021.

Demand will weaken as these trends continue, putting further downward pressure on price inflation. However, those workers who experience falling wages, or who become unemployed, will be unable to take advantage of deflation. Even though workers in a recession badly need deflation to regain some purchasing power for their increasingly scarce income, the central bank will intervene with easy money to keep price inflation positive in the name of “stimulus.” Politically, the Fed will use stagnation-induced deflation as political cover for the Fed to return to aggressive quantitative easing and even lower target interest rates. If employment reports continue to show growing economic stagnation, calls for more monetary inflation and government spending will only grow.

Ryan McMaken is executive editor at the Mises Institute, a former economist for the State of Colorado, and the author of two books: Breaking Away: The Case of Secession, Radical Decentralization, and Smaller Polities and Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Original article link