By Connor O'Keeffe, Mises Wire | February 10, 2026

Last Thursday, the New START Treaty—the last remaining nuclear treaty between the United States and Russian governments—officially expired. Now, for the first time in 54 years, there are no formally agreed-upon limits on each side’s nuclear arsenals.

The Russians offered to agree to a one-year extension of the treaty as both sides worked out a new agreement, but the Americans turned it down.

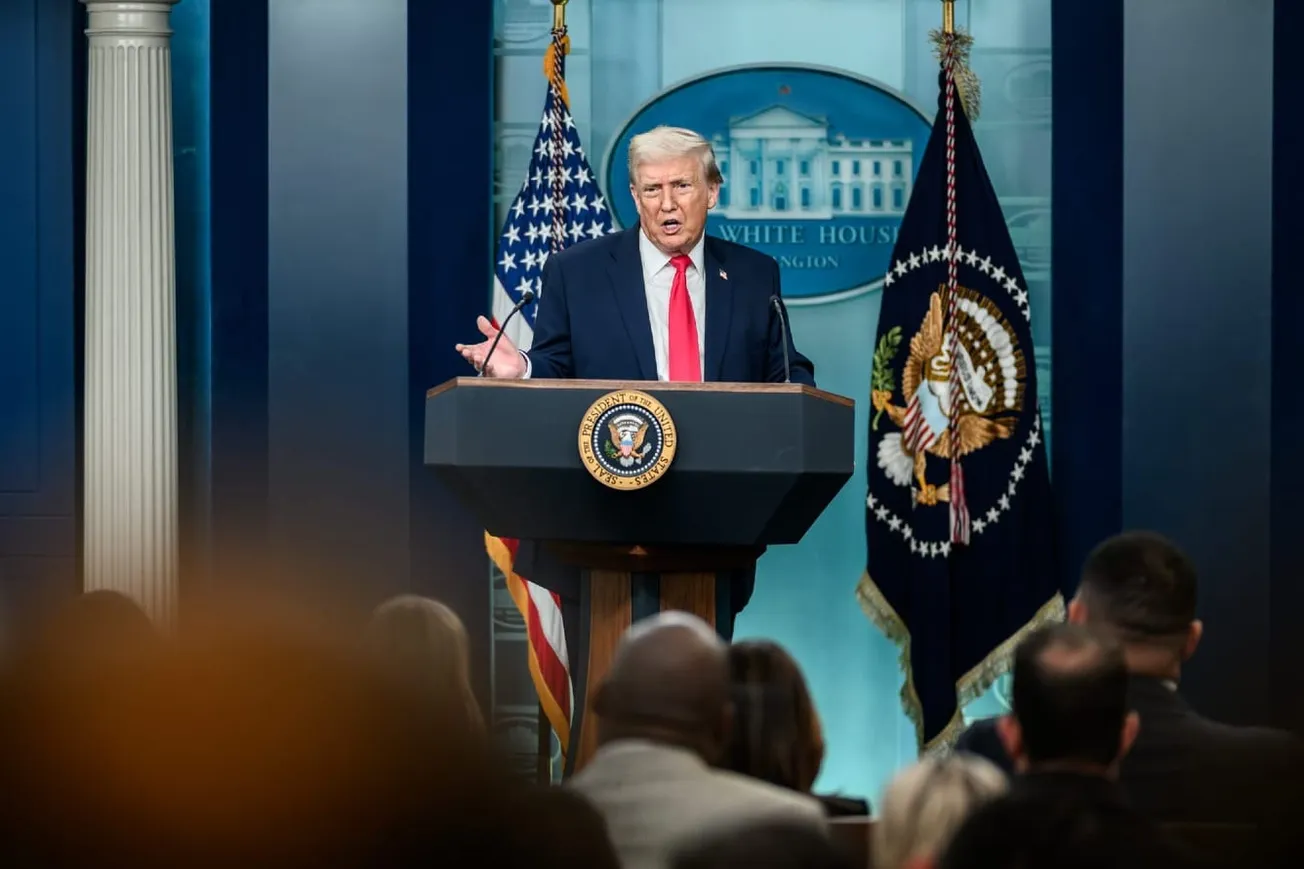

The Trump administration claims it has wanted to walk away from New START because the treaty does not include China. Although, since China’s nuclear arsenal is far smaller than both the US’s and Russia’s, it’s been difficult to make progress towards an agreement that all three governments would accept that does not also effectively give Beijing a greenlight to build its arsenal up to American or Russian levels.

There’s also no reason why Washington’s arms control agreements with Russia and with China had to be one, single, three-party treaty. Trump could have kept the formal limits with Russia in place while pursuing a new agreement with China.

That said, US and Russian officials have reportedly made an informal agreement to continue abiding by the limits laid out in the treaty—a cap of 1,550 deployed nuclear warheads and 800 strategic launchers. That is mildly encouraging, though, as I’ll get to later, the real value of these treaties lies in their verification programs, and it’s not at all clear whether those will continue.

But overall, the administration has been very dismissive of any concerns about the expiration of New START. Not that they’ve had to push that talking point hard; the American public was remarkably apathetic about the story last week. It got its obligatory mentions in the legacy press, but was almost entirely absent from the daily political fights that tend to dominate the more grassroots and independent parts of the media and internet. That isn’t good.

Because, although the administration is probably right when they say the world is not suddenly in an exceptionally more dangerous situation than it was early last week, the end of New START is just the latest step in a much longer tragedy that the American public—and really civilians everywhere—should be far more upset and worried about.

Plenty has been written about the perilous and completely avoidable return to cold war conditions between the US and Russia, as well as the unnecessary risk of a hot war with China over Taiwan. Washington’s decades-old obsession with being the dominant power on Russia’s borders and in the South China Sea put us on a collision course with both regional powers which, at the very least, puts a heavy economic burden on an already-struggling population.

But when we zoom in and look closer at the nuclear component, it becomes clear that the risk on both fronts is far higher than the prospect of another endless war.

Towards the end of the Cold War, and in the years following the USSR’s collapse, significant progress was made to walk the world back from the brink of a nuclear catastrophe. Since the US and Russia controlled the vast majority of the world’s nuclear weapons—a combined total of over 60,000 at the peak—the bulk of that walk back came from treaties and agreements between Washington and Moscow.

Through a series of treaties like the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) in 1972, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) in 1988, the Open Skies Treaty in 2002, and most recently New START in 2010, both sides agreed to limit and, over time, reduce their nuclear stockpiles, bringing us to the current levels of around four or five thousand each.

Denuclearization was, and remains, a great objective. While the complete abolishment of nuclear weapons is not possible, it is possible to bring global levels down below the threshold that would end human civilization if unleashed in its totality—all while preserving or even expanding nuclear deterrence.

But, as I mentioned above, the real value of these treaties and agreements was the verification programs built into them.

To ensure that both sides abided by the agreed-upon limits, all these treaties required the US and Russian governments to be much more transparent about their nuclear forces. Both agreed to grant access to international inspectors, notify each other before any tests, drills, or operations with nuclear-capable weapon systems, and bring deployed nuclear weapons out into the open where they could be easily seen and monitored by the other side’s treaty-sanctioned surveillance flights and satellites.

These measures were obviously helpful for ensuring the treaties weren’t violated. But, most importantly, they greatly diminished the risk of an accidental nuclear exchange between the world’s most heavily-armed superpowers.

There have been very few moments since the Cold War began where the US and Russia stood right on the edge of a deliberate nuclear exchange. But there have been a disturbingly high number of incidents where false alarms risked inciting an actual nuclear attack.

For example, in the 1950s, a US early-warning radar interpreted a flock of birds to be a fleet of Russian planes heading towards the US over the North Pole. In 1960, computers at what was then Thule Airbase in Northern Greenland determined that the moon rising on the horizon was a swarm of hundreds of nuclear-capable ballistic missiles flying from Russia. In 1979, a simulated exercise tape was accidentally loaded into a NORAD computer, which convinced analysts that the US was under nuclear attack.

Famously, in 1983, the Soviet early warning system reported that the US had launched ICBMs at the USSR, prompting Soviet forces to begin the process of retaliating—only for an officer to likely save the world by disobeying his orders to move that process forward on a hunch that the attack wasn’t real. And then, in 1995, the launch of a US-Norwegian research rocket put Russian nuclear forces on full alert and even led the Russian president to activate his “nuclear football” and retrieve launch codes before it was determined to likely be a false alarm.

The transparency and access each side granted the other in the various arms control treaties didn’t eliminate the risk of these sorts of false alarms resulting in a real nuclear launch—largely because the entire command-and-control system of both countries has operated on a hair-trigger, “launch on warning” protocol for their respective land-based Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). It did, however, greatly reduce the risk that the false alarms would be taken seriously in the frantic few minutes this delicate nuclear setup gives decision-makers to choose whether and how to retaliate.

But, one by one, those safeguards went away with each treaty that was either abandoned or allowed to expire. That started with the ABM Treaty in 2002, the INF Treaty in 2018, Open Skies in 2020, and New START last week.

As the verification arrangement has unraveled, the situation has grown even more dangerous. After the Bush administration used its war propaganda about a nuclear-armed Iraq as an excuse to abandon the ABM treaty—a move that was likely actually motivated by an interest in developing banned missile defenses—Russia used the opportunity to develop its Poseidon nuclear-armed torpedo and a slate of more advanced hypersonic ICBMs that cannot be stopped by American missile defenses.

Then, when Trump pulled out of the INF Treaty in 2018, the Russians went on to develop the Oreshnik missile, which has already been used to deliver non-nuclear warheads at speeds as high as Mach 10 in strikes on Ukraine.

Yet as Russia’s offensive capabilities have grown more advanced, its early warning system has remained alarmingly ineffective. According to MIT’s Ted Postol, instead of looking down at the Earth like US satellites do to detect rocket plumes, Russian satellites have to “look sideways” to detect missiles launching into the atmosphere—which can make it hard for their system to distinguish sunlight and high-altitude clouds from actual incoming missiles.

So, as tensions have risen, a proxy war has broken out, nuclear weapons have gotten even more powerful while nuclear defenses have remained just as ineffective, hypersonic missiles have cut down on the time decision-makers have to consider and respond to perceived attacks, and treaty-brokered transparency has broken down while Russia’s early warning system continues to struggle, there is now, once again, an unacceptably high risk of an accidental nuclear exchange between the US and Russia.

Yet, again, the American public has so far been pretty apathetic about all this. To be fair, proponents of the US providing military support to Ukrainian forces did spend a lot of time and energy dismissing any concerns about the nuclear risks of the US getting highly involved in the war with Russia. And, overall, there’s a sense that nuclear war is an antiquated concern. But in the absence of public pressure, the situation has grown even more dangerous.

This is because the most dominant groups influencing US nuclear policy are now the weapons companies and members of Congress working to expand America’s ICBM program—groups William Hartung calls the ICBM lobby. Specifically, in 2020, the “defense” contractor Northrop Grumman was awarded a massive contract to develop a new missile to eventually replace the current Minuteman III ICBMs. The project—which is named Sentinel—has since gone wildly over-budget, but has continued despite warnings from insiders that ICBMs are an antiquated and extremely risky component of the nuclear triad—simply because it’ll bring revenue to the contractor and jobs to several northern states.

So, again, while the specific danger brought about by last week’s formal expiration of New START could be minimal in a vacuum, the broader context in which it’s taking place is incredibly disturbing. It highlights the completely unnecessary march that we are being forced to bankroll and endure, back to the most perilous days of nuclear brinksmanship. We must not go silently.

Connor O’Keeffe writes a weekly column for the Mises Wire, hosts Guns & Butter a weekly podcast on current trends, and produces media and content at the Mises Institute. He has a master’s in economics and a bachelor’s in geology.

Original article link