Ebrahim Raisi, Iran's hardline president, has been laid to rest with full state honors after he died in a helicopter crash last Sunday. The news of the accident sent shockwaves through the world, and all eyes turned to Tehran to see how the establishment would react to his sudden demise.

Iran's eighth president, the late Raisi, leaves behind a 'mixed legacy,' as evidenced by the reactions from within Iran and outside. There have been reports that many Iranians risked punishment to celebrate, distributing sweets and bursting firecrackers. Meanwhile, television channels have been airing visuals of large crowds at public mourning sessions and funeral services. The US and Israel were quick to deny any involvement in the accident, and world leaders stepped up to offer messages of condolence.

Raisi, a former judiciary chief, became a highly divisive figure as he rose through the ranks to become the highest elected official of the repressive Islamic Republic of Iran. He earned the approval of the powerful Ayatollahs, the supreme leaders of the Shiite Muslims, for his role in the torture and extrajudicial murders of thousands of political prisoners ordered by Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, in 1988-89. It is estimated that 30,000 people were executed in the name of 'annihilating the enemies of Islam.' Raisi earned the nickname "Butcher of Tehran" due to his involvement in the mass execution. Like many other autocratic leaders of the past and the zealously religious clerics he served, Raisi claimed during his presidential bid in 2017 that it was his "religious and revolutionary responsibility to run" for office.

Even after coming to power, Raisi continued his radical policies, winning the support of the hardliners and the hatred of the citizens. Steadfast in his approach as President, he ordered the quashing of protests in 2022 that erupted after Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman, died after being detained by the conservative police for allegedly wearing her hijab "improperly." With his ultra-conservative outlook and iron-fisted rule, the relatively young 63-year-old Raisi was tipped to succeed Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei when the time came.

Beyond Iran's borders, too, Raisi flexed his muscle after becoming President. Despite Washington's desperate efforts, he let the Iran nuclear agreement, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), die. Ignoring stringent sanctions and international censure, he moved ahead with the country's nuclear program, claiming that it was for peaceful purposes. Tehran's support of Russia and non-state actors in West Asia, namely Hamas, Hezbollah, and Houthis, had raised tensions in the region and left the country largely isolated on the world stage. Iran's audacious and unprecedented missile attack on Israel, in retaliation for the attack on its Syrian consulate, threatened to bring things to a boil in the Middle East.

But those who follow Middle East politics do not expect anything to change with the unexpected death of Ebrahim Raisi. In a country like Iran, it is hardly the man who steers the country. Yes, Raisi ran Tehran’s foreign policy – with the blessings of the Supreme Leader. Yes, he was adept at negotiating between the executive, judiciary, and legislature while portraying himself as deeply religious. But, despite atrocious suppression, dissent among the people is growing. Religious dogmatism is facing increasing opposition. It is simmering under the surface and spilling onto the streets. The country’s economy is in tatters, and nostalgia for past achievements is not enough to silence the as-yet-muted critics.

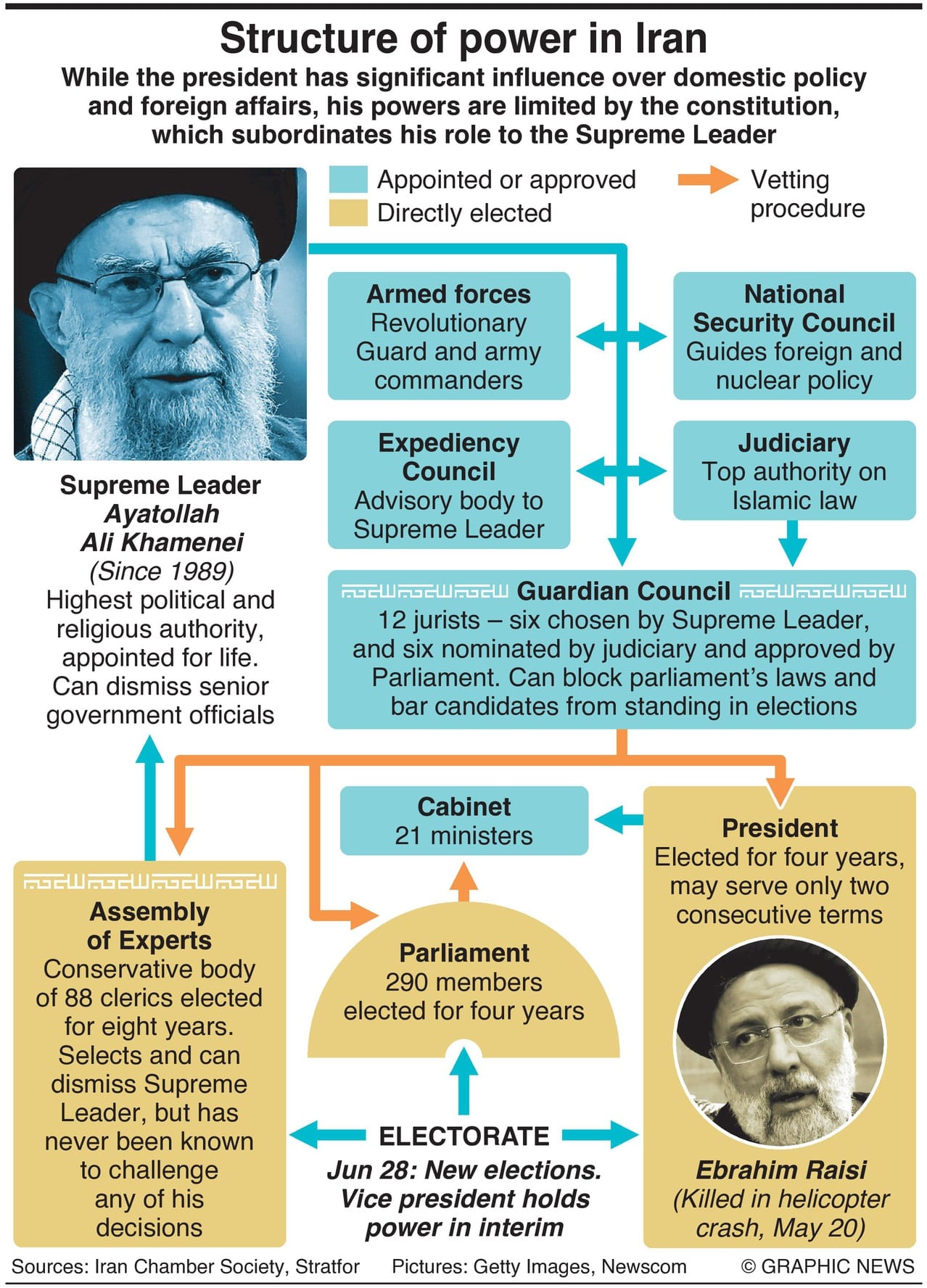

The task before the Iranian clergy is clear – stay the political course in the face of the unexpected event. And they are doing just that. Tehran has already announced that elections will be held on June 28, and the first vice president has been appointed interim president. As the Supreme Leader declared mere hours after the news of the accident broke, “the nation would not be disrupted at all.”

The office of the presidency is largely for domestic politics, but the Supreme Leader controls Iran's engagement with foreign nations, including its nuclear program. There's a risk that Iran could become even more conservative with rumors that the Supreme Leader's son, himself a cleric, is either in the run for the office of the presidency or to become the new Ayotollah.

The death of the “Executioner of Tehran,” therefore, signifies not a turning point but a mere blip in the continuum of a regime rooted in repression. Meaningful change for the people of Iran is not in sight and can only occur through a collective uprising of a population yearning for freedom. Until then, the oppressive state grinds on, undeterred by the fall of one of its own.