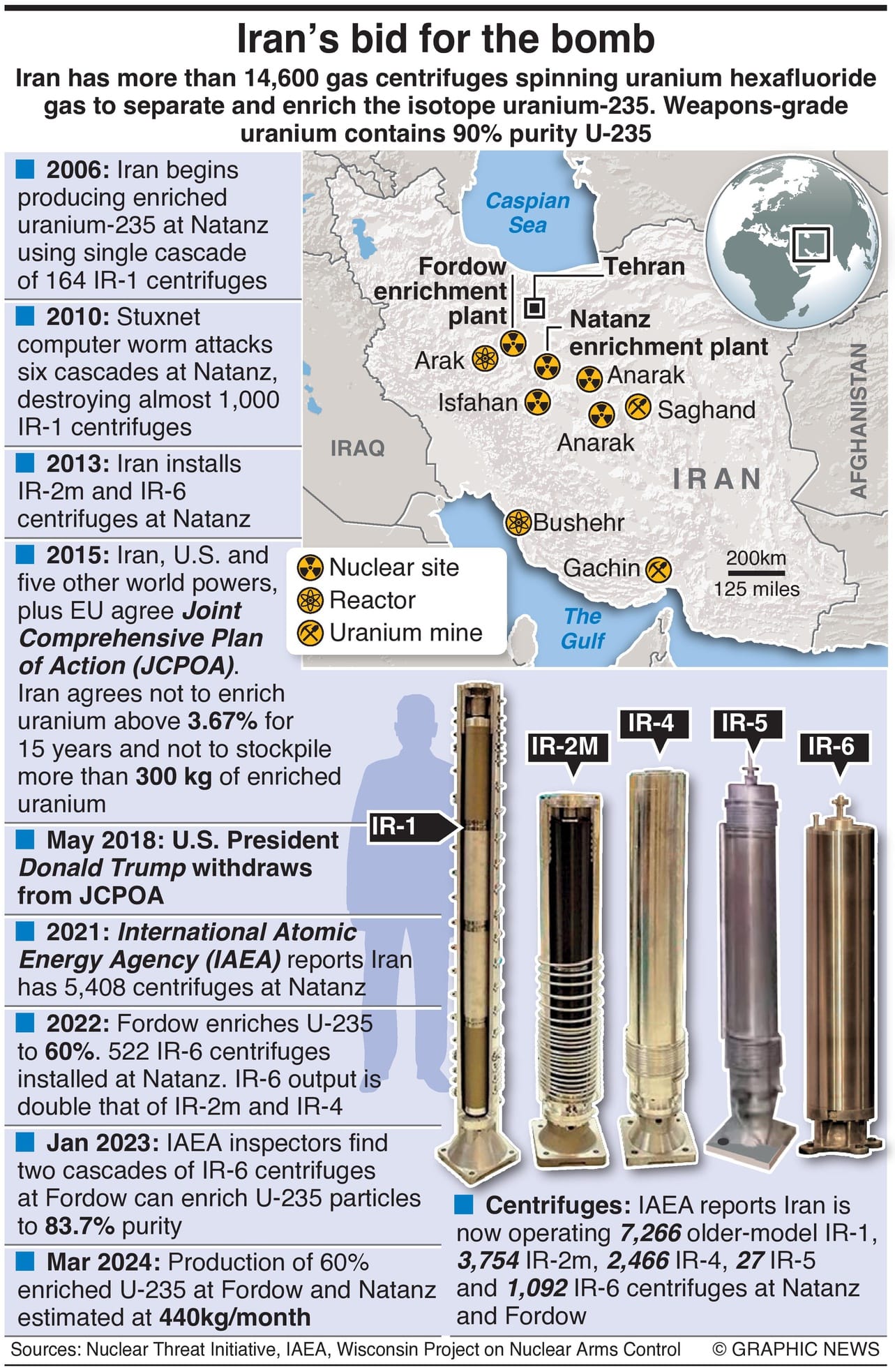

Antony Blinken, the U.S. Secretary of State, recently stated at the Aspen Security Forum, 'Iran, because the nuclear agreement was thrown out, instead of being at least a year away from having the breakout capacity of producing fissile material for a nuclear weapon, is now probably one or two weeks away from doing that.'

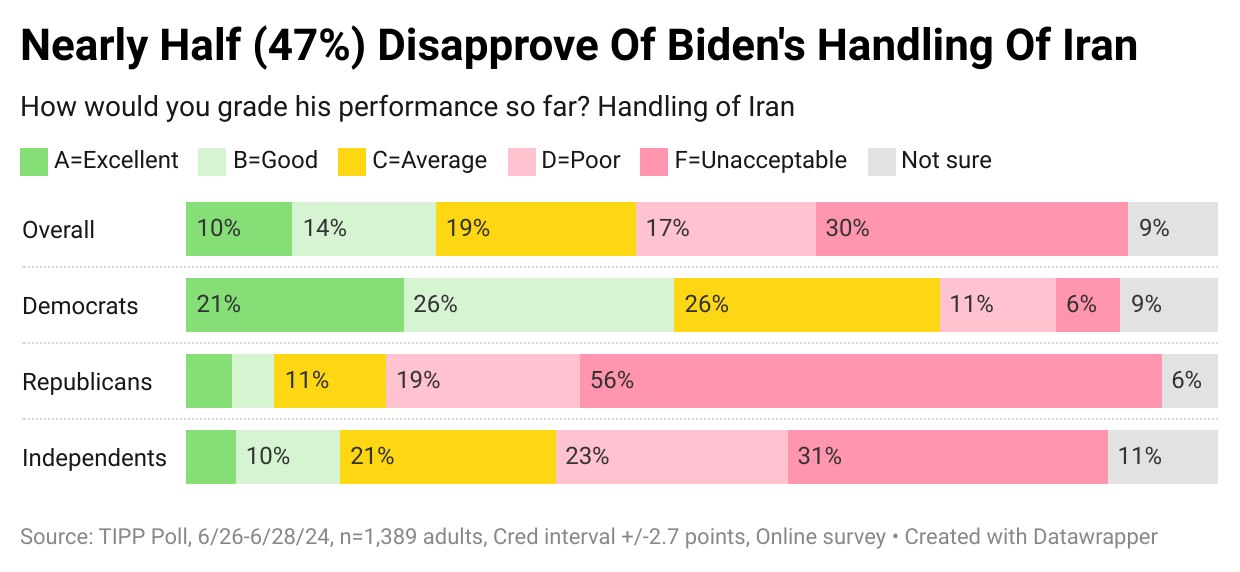

Since then-President Trump pulled America out of the Iran nuclear deal, also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), in 2018, Tehran has made great strides in advancing its nuclear capabilities. The Biden administration spent more than a year after it came to power in efforts to revive the deal, engaging in indirect talks with the Iranian government. However, the talks failed, and most believe the JCPOA is beyond revival as the circumstances have changed incomparably. While Blinken mentioned that diplomatic efforts are on to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon, the success of such overtures is far from guaranteed.

The dire prediction from Blinken comes at a time when power in the capitals is changing hands. After desperately trying and failing to revive the nuclear pact or contain Khamenei's regime, the Biden administration is on its way out. Should Trump return to the White House, he is unlikely to adopt a softer approach with the orthodox regime than he did in the past.

And, it's not only Washington that is poised for a change of guard. Iran was forced to go to the polls after President Ebrahim Raisi died in a helicopter crash. Sixty-nine-year-old cardiologist turned politician Masoud Pezeshkian emerged the winner in an election that many boycotted in protest against the regime.

But those who did vote chose the moderate, reformist Pezeshkian over his opponent, Saeed Jalili, a super-revolutionary close to the clerical establishment. Jalili advocated tougher policies towards the West and stricter enforcement of the Islamic moral code.

The low-profile politician Pezeshkian is no novice. He served as Iran's Deputy Health Minister and Health Minister at the turn of the millennium and has been an elected member of the country's parliament since then. A moderate voice in Tehran's politics, Pezeshkian had bid for the office twice before but gave way to other candidates before the polls. Now, he has to walk the tightrope between his reformist agenda, on which he was elected, and the conservative clerical establishment that balks at the notion.

As Mahsa Amini's death at the hand of Iran's moral police rocked the nation, the moderate Pezeshkian took to X (formerly Twitter), writing, "We oppose any violent and inhumane behavior towards anyone, notably our sister and daughters, and we will not allow these actions to happen."

The President-elect, set to take charge in early August, has expressed his willingness to engage with the West, though he can hardly be termed an ally. He said, "If we manage to lift the sanctions, people will have an easier life, while the continuation of sanctions means making people's lives miserable."

The two instances indicate a marked deviation from his predecessor. His open advocacy for human rights, especially women's rights, is commendable, as is his willingness to work with the West to better the lot of his people.

Pezeshkian's approach or intentions may differ, but other than a change of face, nothing much is likely to change in the Islamic Republic. Because in Iran, the ultimate power resides with the Supreme Leader, not the elected president. He is the head of state, commander-in-chief, and highest-ranking religious authority in the country. And from Iran's Supreme Leader, Seyyed Ali Hosseini Khamenei, who directs international policy, Washington's expectations are "limited."