A tippinsights EB member transited through Paris CDG airport last Friday morning. The huge terminal 2E, serving various international destinations, was practically empty. Security lines were a breeze; even the exits to baggage claim and Paris's welcoming doors appeared deserted. Many connecting flights departing were not even half-full - like the one in which our colleague traveled.

It is not a scene one expects on a late summer Friday morning in one of the world's greatest and tourist-friendly cities. Our conclusion from the airport experience alone is uncharacteristically unscientific, but it anecdotally supports media stories that the world economy is in trouble.

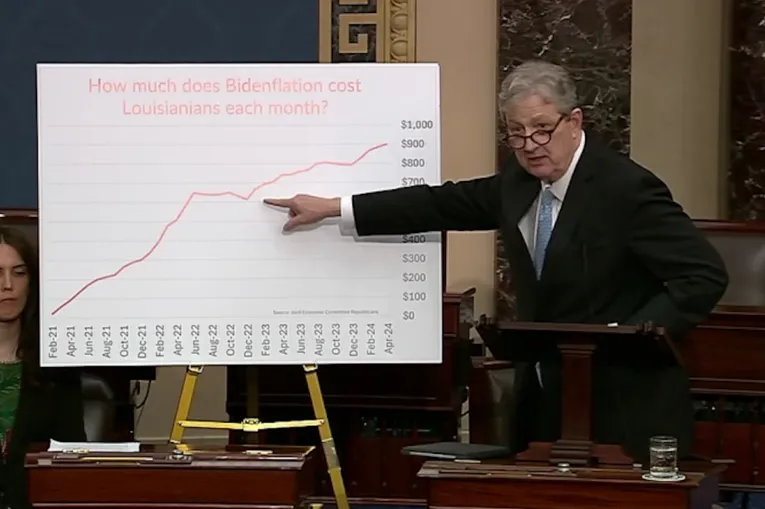

Eight time zones away, Reuters reported on Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell's speech at the annual economic symposium hosted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. In America, the problem is the opposite of what is confronting Europe. U.S. inflation continues to be high because of tight labor markets and persistently above-trend growth.

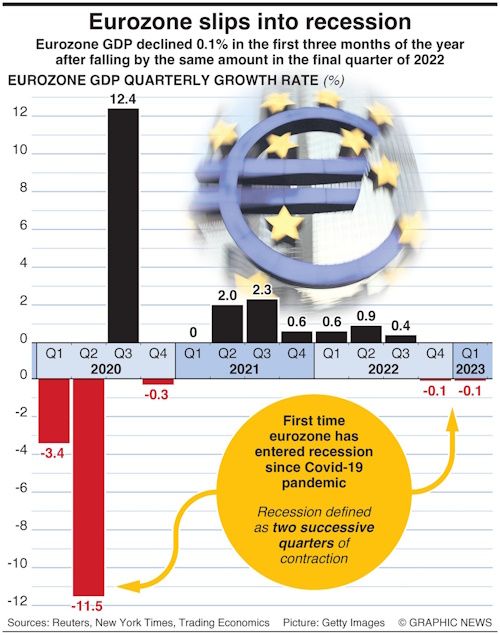

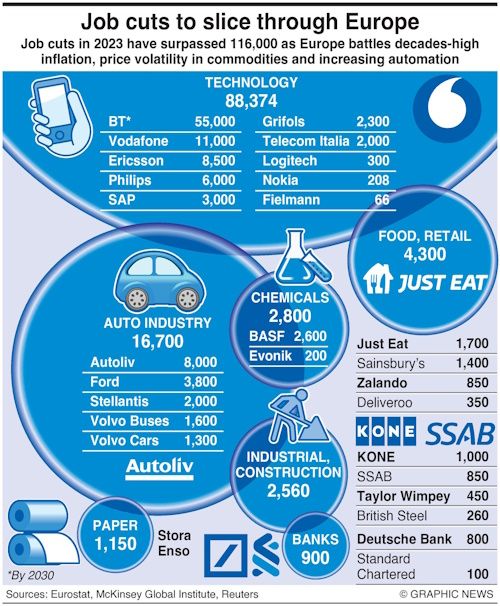

Meanwhile, Germany is already in a recession in Europe, and the U.K. is skirting one - yet prices are so high that millions of middle-class citizens feel impoverished. Europe's problems are far worse than America's, and America's foreign policy in Ukraine, which Europe has obediently adopted as its own, has much to do with it.

Powell's concerns were all about inflation and increasing interest rates.

Although inflation has moved down from its peak - a welcome development - it remains too high. We are prepared to raise rates further if appropriate and intend to hold policy at a restrictive level until we are confident that inflation is moving sustainably toward our objective. Two percent is and will remain our inflation target. We are committed to achieving and sustaining a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to bring inflation down to that level over time.

On the labor market front, he said:

Evidence that the tightness in the labor market is no longer easing could also call for a monetary policy response.

Central banks must manage three crucial macroeconomic factors: inflation, unemployment, and economic growth, keeping all three in a Goldilocks range. It is like a game of Whack-a-Mole. No matter how skilled one is, one of the three always shows its ugly head. They regulate the money supply by setting commercial and retail banks' interest rates and reserve limits. They lower interest rates to spur economic growth and increase them when the economy becomes too hot.

This simple trick would work, but after the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed engaged in an untested practice called quantitative easing that the European Central Bank dutifully followed. They created money from thin air and flooded markets, something they could do because all modern currencies are fiat instruments, meaning they are not backed by gold or some other commodity. This went on for nearly ten years when the world's central banks injected over $10 trillion in free cash.

When governments splurged populations with additional free cash during the pandemic, the problem became worse. Many households had too much money in their savings accounts. Because the service industry was locked down (restaurants, salons, bars), families began to buy physical products like washing machines from the extra cash they had. But lockdowns affected factories too, so production levels were much lower than usual. The world fell into a classic case of demand-pull inflation: Too much money chasing too few goods.

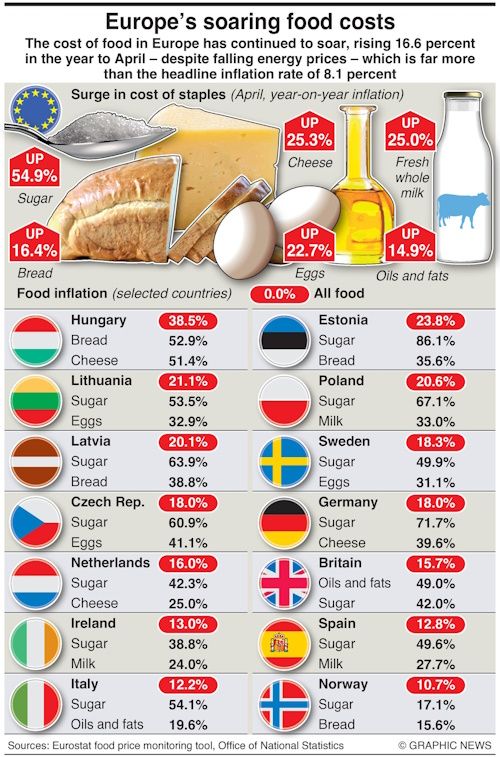

It took the globe more than two years to ease out shortages due to supply chain difficulties as factories slowly came back to life (labor strife at ports exacerbated the situation). But when Russia invaded Ukraine, Washington foolishly sought to aggressively punish Russia by imposing severe sanctions on a country that is a significant producer of numerous items that the world needs - soybean, wheat, fertilizer, chemicals, oil, and natural gas. The sanctions theoretically exempted these items, but they became collateral damage. Historically dependent upon Russia as a trading partner and a buyer of Russian energy, Europe, mainly Germany, chose to cut itself off from Moscow altogether. Supply chain shortages returned with a bang, hurting Europe much more than America.

As prices soared again (in August 2022, energy prices in the UK went up 80% from six months prior), central banks struggled to contain the fallout with the only tool they know: shrink the money supply. The Fed Funds rate is now at 5.25%. Consumers are not used to such high levels, having been fed on a near zero-interest rate diet throughout the years when quantitative easing was rampant. Many big-ticket items, such as homes and cars, are generally financed with borrowed money. Last week, the rate on 30-year residential mortgages in the United States reached 7%, the highest in 15 years. We calculated that an average family with a $500,00 loan would have to allocate nearly $3,300 monthly, not including taxes, insurance, and maintenance. That is an extraordinarily high burden on even double-income middle-class families.

The Bank of England raised its interest rate for the 14th time in August, bringing the country's lending rate to 5.25%. Lines at food banks have increased as Britons are struggling to eat. The ECB has been a laggard, increasing rates only nine times to 4.25%.

Even at this relatively lower level, Marcel Fratzscher, the President of the German Institute For Economic Research and one of the country's most eminent economists, told NPR in July:

People are worried about their jobs. People are worried about what they have achieved in the past. And the first sign of that is high inflation currently. Most people, particularly those with low incomes, are experiencing a massive cut in the purchasing power of their income and living standards. So people are scared.

Given the dire situation, to limit demand, the ECB will have to raise rates even higher. But increasing rates in Germany, which is in a recession, is the exact opposite thing to do. One lowers rates to stimulate the economy, not make money tighter.

It is a terrible time to be a Central bank official, especially in the West. And the sad truth is that no Central Banker knows how all of this will play out.

We could use your help. Support our independent journalism with your paid subscription to keep our mission going.