By George Ford Smith, Mises Wire | February 11, 2025

The Fed is in the business of generating inflation. It might attempt to stop the effects of inflation, namely rising prices. But under the old definition of inflation — an artificial increase in the supply of money and credit — the entire reason for the Fed’s existence is to generate more, not less of it. — Ron Paul, End the Fed (emphasis mine)

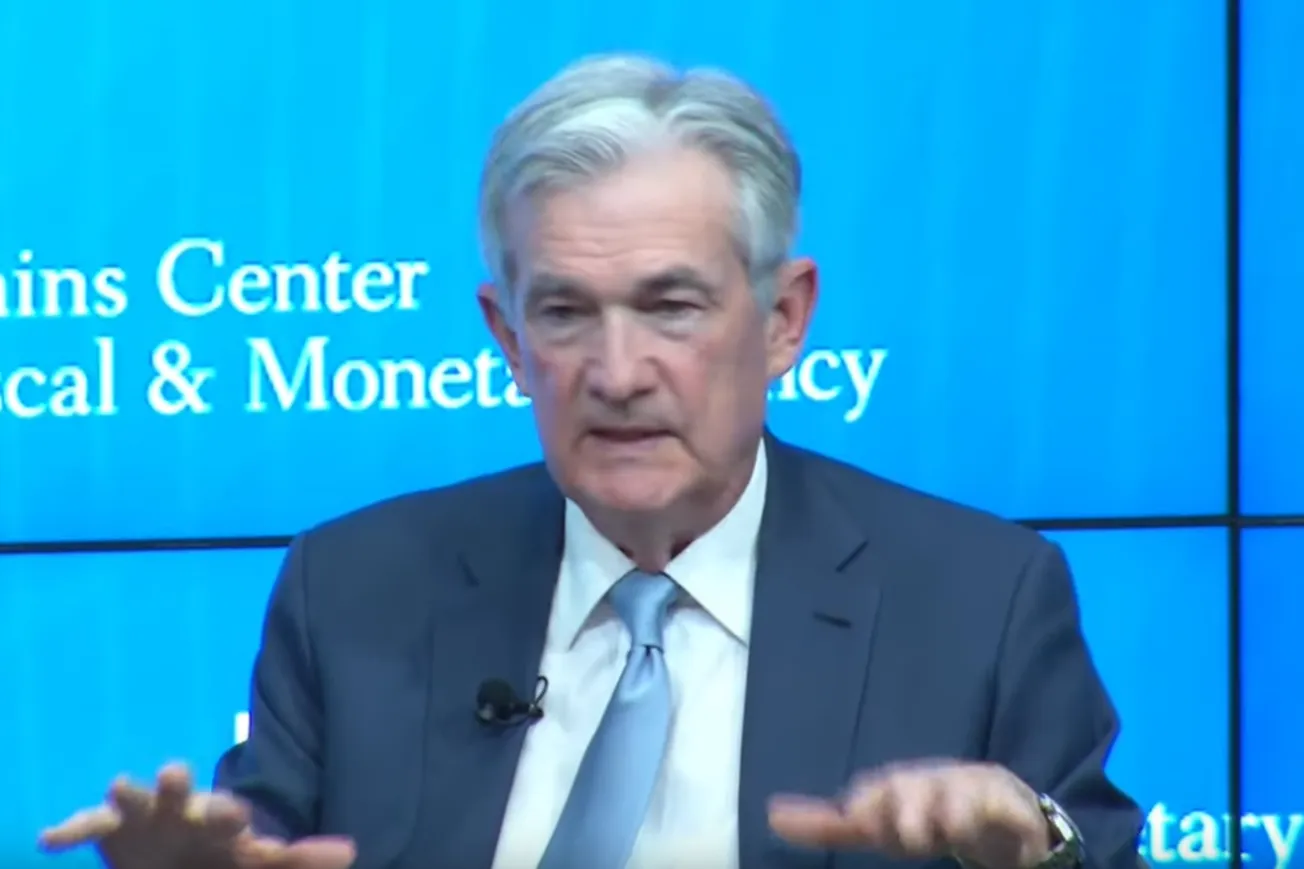

It’s probably unfair to liken the 1998 Peter Berg dark comedy Very Bad Things to the activities of the US Federal Reserve, but the central bank does share the traits of incompetence and disastrous results with the bumbling wedding party in the film. When one considers the legacy of the Fed since its inception in 1913, it may be that nothing comes close to the damage the Fed has done to people’s lives. And there’s clearly nothing funny about it. One would think monetary economics is an arcane art beyond man’s comprehension, and the best we can do is what we’re doing: Hire smart guys to take educated guesses about what needs to be done. Yet, its mystery is purely man-made.

In its broadest sense, economics can be thought of as the study of exchanges. This is how it is defined by Robert Murphy, author of an unusual textbook called Lessons for the Young Economist. It’s unusual in that it’s methodical without being tedious. In fact, it’s downright fascinating.

The economists who were blindsided by the 2008 crisis were neck-deep in charts, aggregates, and bad theory they believe in to this day. They tell us no one saw the train coming, so if everyone was blind, no one was blind. They insist the train wreck was just an unfortunate reminder that economics is hard stuff. Better to leave it to the experts at the Fed where high IQs run rampant.

The problem is economists of the Austrian School, such as Murphy, saw the train coming as soon as it left the station. Every train that leaves the interventionist station has its fate written in economic law, as expounded in the works of Mises, Hayek, Rothbard, Paul, and others. Everything that has happened since 1913 has had all the suspense of a bad novel—for Austrians.

Did the Fed inflate prior to the 2008-2009 financial meltdown? Like mad. Perhaps at Paul Krugman’s suggestion, Alan Greenspan created a monster housing bubble to replace the dot-com bubble. Did it inflate in response to the bust? Bernanke spiked the monetary base. Were investors calling for even more monetary pumping? The ones calling for QE3 were. And there are countless nervous others hovering around the panic button ready to join them.

Murphy’s book—though geared to bright middle schoolers—provides the tools for understanding what the interventionist crowd seems unable to grasp, which is this: unhampered markets have built-in regulatory mechanisms that keep the train on the tracks. And the issue at stake could not be more critical. As we read in Lesson One of Murphy’s book:

Unlike other scientific disciplines, the basic truths of economics must be taught to enough people in order to preserve society itself. It really doesn’t matter if the man on the street thinks quantum mechanics is a hoax; the physicists can go on with their research without the approval of the average Joe. But if most people believe that minimum wage laws help the poor, or that low interest rates cure a recession, then the trained economists are helpless to avert the damage that these policies will inflict on society.

The world’s policymakers as well as the people who suffer under them could benefit enormously from committing that passage to memory. We have, in essence, exchanged sound economic principles for very bad ones—ancient fallacies framed in modern jargon—and are now wondering why the economic outlook is so threatening.

The idea of “exchange,” though, is not limited to the trading activities of individuals in which goods and services are traded for money or for other goods and services. In every aspect of our lives we’re confronted with the possibility of exchanging the status quo for something else. The exchange can be performed by an individual in isolation, such as the shipwrecked fictional character Robinson Crusoe who must build a one-man economy, or the change can be brought about by people acting together. . . as American voters did recently.

Exchanging Education for State Indoctrination

In the early 19th century, educational reformers began “exchanging” the Jeffersonian system of voluntary parental education for a more collectivist approach inspired by the despotic Prussian system. Jefferson was a strong advocate of public schools for the poor, but an equally staunch opponent of compulsion in education. Yet, by the end of the 19th century almost every state had compulsory public schools, in which the “virtues” of obedience, equality, and uniformity were inculcated, sometimes violently, while independent thinking was discouraged or punished.

Given the educational system, should we be surprised that government inroads into the economy and our private lives take place without much resistance?

In 1913, we exchanged a high tariff for the income tax, then we got a high tariff again in 1921.

In 1917, we exchanged peace for war, then peace for war again a generation later. After that, peace for perpetual war.

In 1933, we exchanged economic liberty for a form of economic fascism. It still bears the name of “free market capitalism,” though, which is useful for confusing people when the fascists in power screw things up.

After 2001, we exchanged freedom for security and are getting less of both.

But the biggest disaster has been the exchange of market money for political money, initiated in 1933 and completed in 1971. Every American and dollar holder is now at the mercy of bureaucrats instead of the market.

In economics, all voluntary exchanges are win-win agreements at the time of the transaction. Both sides to the trade believe they’re improving their lot, otherwise they wouldn’t agree to make it. When politicians take to making exchanges for our benefit, however, we’re almost always on the losing side. Someone must be winning, but in the end it’s not clear who.

George Ford Smith is a former mainframe and PC programmer and technology instructor, the author of eight books including a novel about a renegade Fed chairman (Flight of the Barbarous Relic) and a nonfiction book on how money became an instrument of theft (The Jolly Roger Dollar)

Original article link