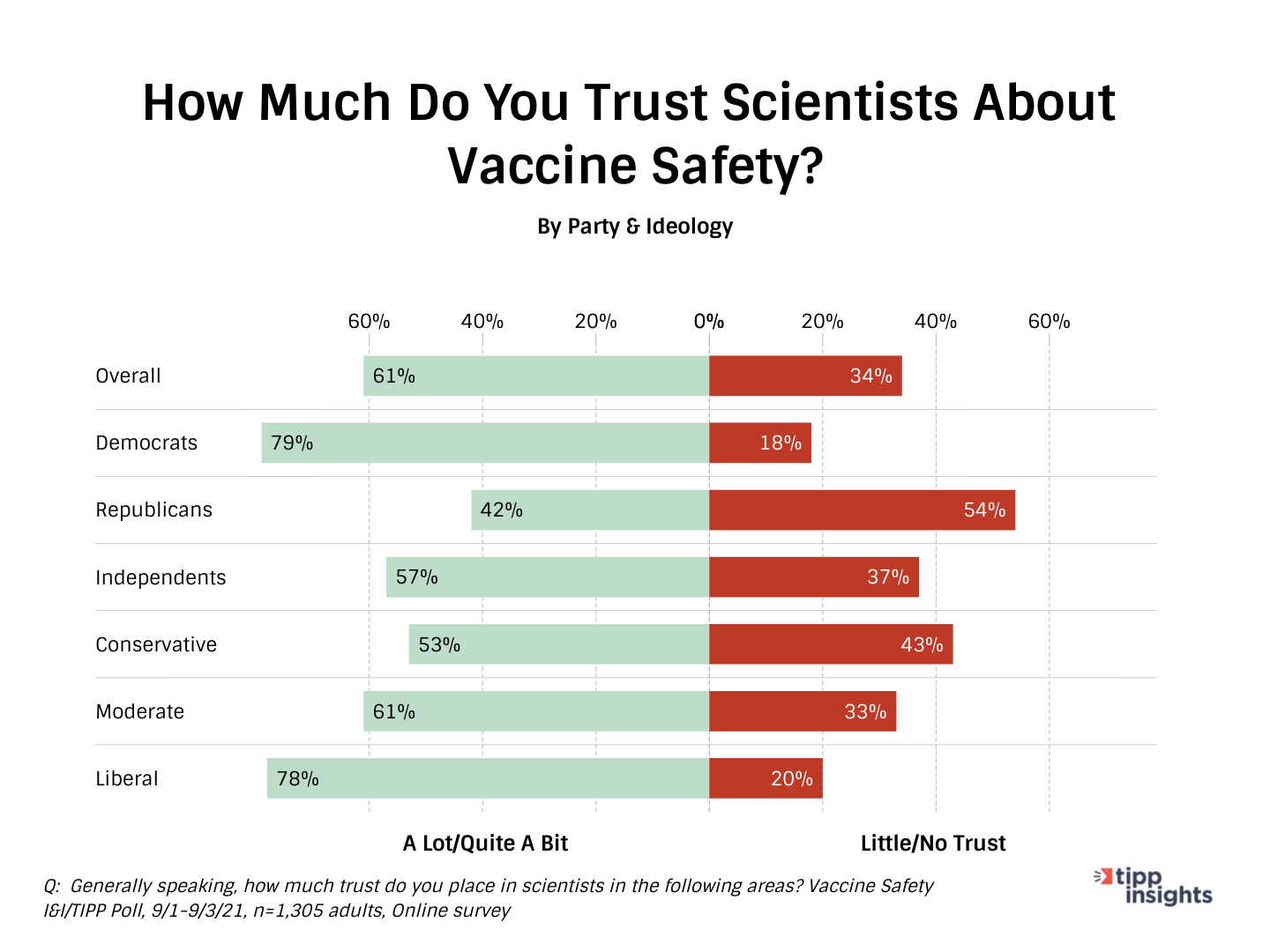

From coronavirus vaccines and the virus’ origin to climate change, a substantial portion of the country distrusts scientists to do their jobs honestly and capably. The latest data from the September Issues & Insights/TIPP Poll also found significant differences among Americans of different political views, reflecting a growing politicization of science in America.

The I&I/TIPP poll asked Americans, “how much trust do you place in scientists” in three areas of science prominent in today’s headlines: “vaccine safety,” “climate change,” and “coronavirus origin.”

Overall, among the three, vaccine safety was tops in scientist trust, at 61%. Perhaps not surprisingly, that almost perfectly matches the share of the U.S. population currently vaccinated: 63%.

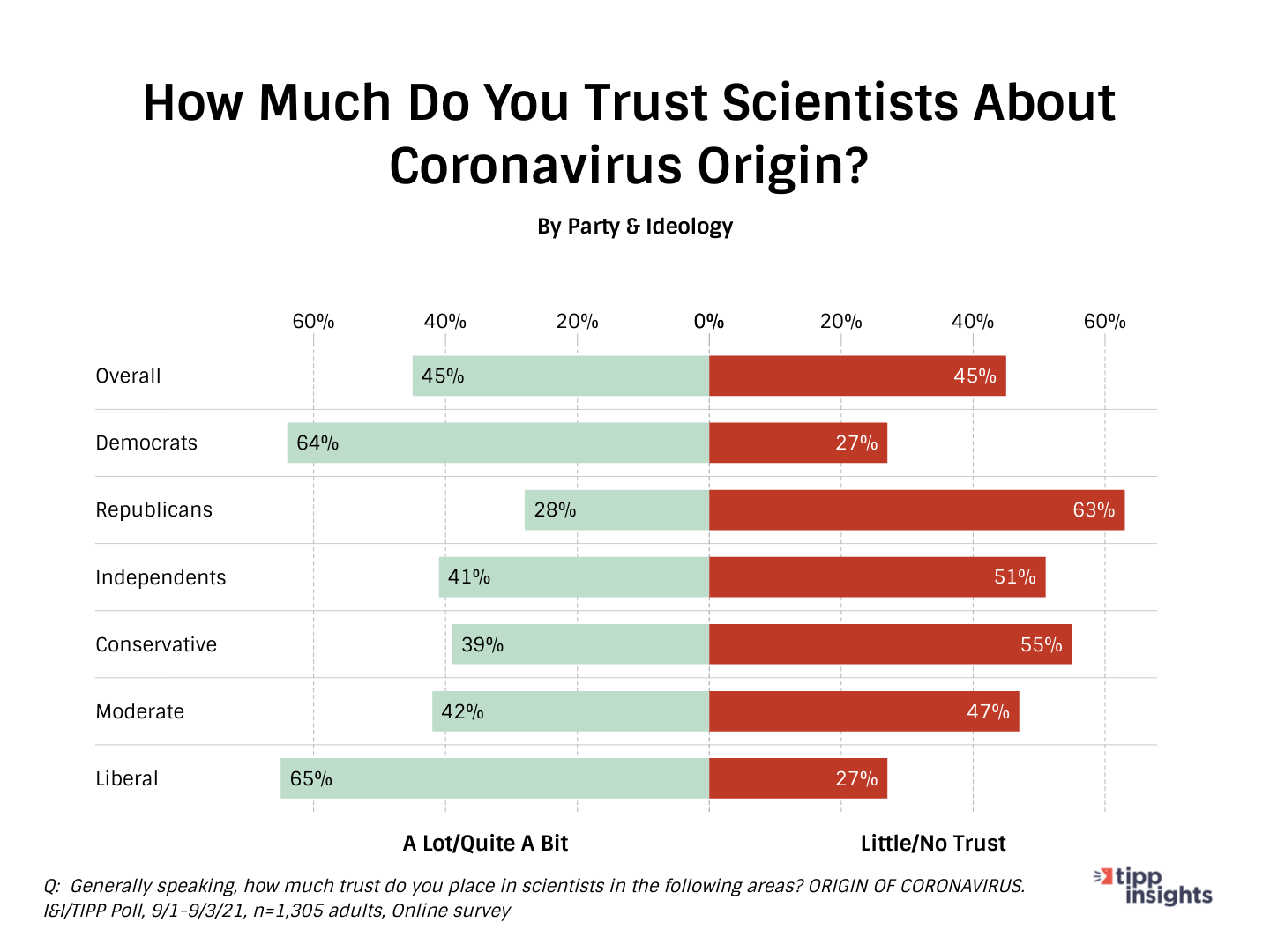

But just 45% said they trusted scientists when it comes to the actual origins of the coronavirus. A scientific debate has raged over whether the virus originated in a Wuhan “wet market” or in the Chinese-government-run Wuhan Institute of Virology.

The debate revived this month after revelations that the U.S.’ top COVID-19 scientist, Dr. Anthony Fauci, helped fund dangerous gain-of-function virus research at the Wuhan lab. That laboratory has been implicated as the likely site for the creation and subsequent release of the deadly COVID-19 virus.

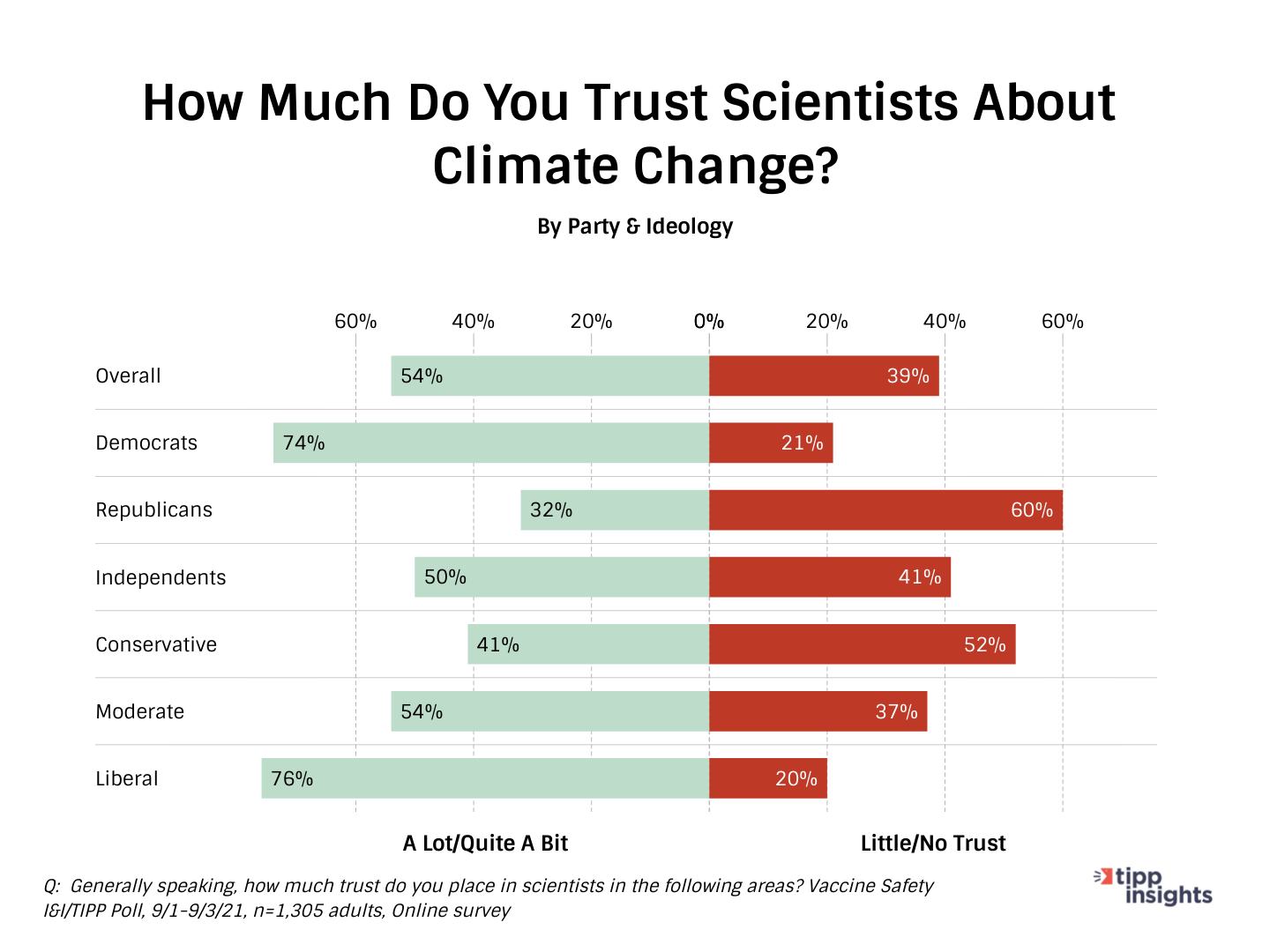

As for climate change, just 54% of those queried said they trusted scientists, a sign of significant mistrust despite overwhelming media sensationalism and extreme political bias on the global warming issue.

September’s data come from the monthly I&I/TIPP poll, conducted by TechnoMetrica Market Intelligence, I&I’s polling partner. The online poll of 1,305 adults was taken from Sept. 1 through Sept. 3. The poll, part of a broad new public opinion collaboration between Issues & Insights and TIPP, has a margin of error of +/- 2.8 points.

By far, the greatest differences of opinion on these questions seem to come from political party affiliation.

For instance, on the question of trusting scientists on vaccine safety, Democrats (79%) were far more likely to trust them than either Republicans (42%) or independents/other (57%). On the origins of COVID-19, a similar split could be seen: Dems (64%), GOP (28%), and independents (41%).

Climate change showed the widest political divisions of all when it came to trusting the scientific community: Dems (74%), GOP (32%), and independents (50%).

Climate change, which has been a polarizing political issue for three decades, suffers from public perceptions of exaggerated threats, questionable data, and bad predictions from climate models.

Most Republicans and a significant share of independents see climate change policy, over the years largely driven by the Democratic Party, as a cynical attempt to impose greater government control over the economy and Americans’ lives. Meanwhile, for many if not most Democrats, ending the use of fossil fuels and slashing carbon dioxide emissions amount to nothing less than a civilizational survival imperative.

When President Joe Biden recently called climate change the “greatest threat” to U.S. national security, it was a message that surely confused and angered many voters, who in polls routinely rank climate change at or near the bottom of their list of key concerns. Politicians and others who claim “the debate is over” only infuriate those who remain skeptical of the science, helping to further exacerbate political differences.

In such a hyper-politicized environment, even the most apolitical of scientists can get hit by the partisan crossfire.

Moreover, the massive volume of research on these scientific topics is overwhelming and often contradictory, leading to public confusion and mixed messages from policymakers. In recent years, more than half of peer-reviewed studies in some scientific disciplines can’t be reproduced by other scientists, a sign of something deeply wrong in science.

The problem has grown worse during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has been further amplified by both social media and phony so-called experts, explains John Ioannidis, a professor of medicine, epidemiology and population health at Stanford University:

Anyone who was not an epidemiologist or health policy specialist could suddenly be cited as an epidemiologist or health policy specialist by reporters who often knew little about those fields but knew immediately which opinions were true. Conversely, some of the best epidemiologists and health policy specialists in America were smeared as clueless and dangerous by people who believed themselves fit to summarily arbitrate differences of scientific opinion without understanding the methodology or data at issue.

Of note, the I&I/TIPP data were collected before Biden’s recent decision to require companies with 100 employees or more to vaccinate all their employees.

The data appear to bolster recent comments even by some scientists of a growing public crisis of confidence in science in general and scientists in particular.

Terry Jones is editor of Issues & Insights. During his four decades of journalism experience, he served as both associate editor and editorial page editor for Investor’s Business Daily.

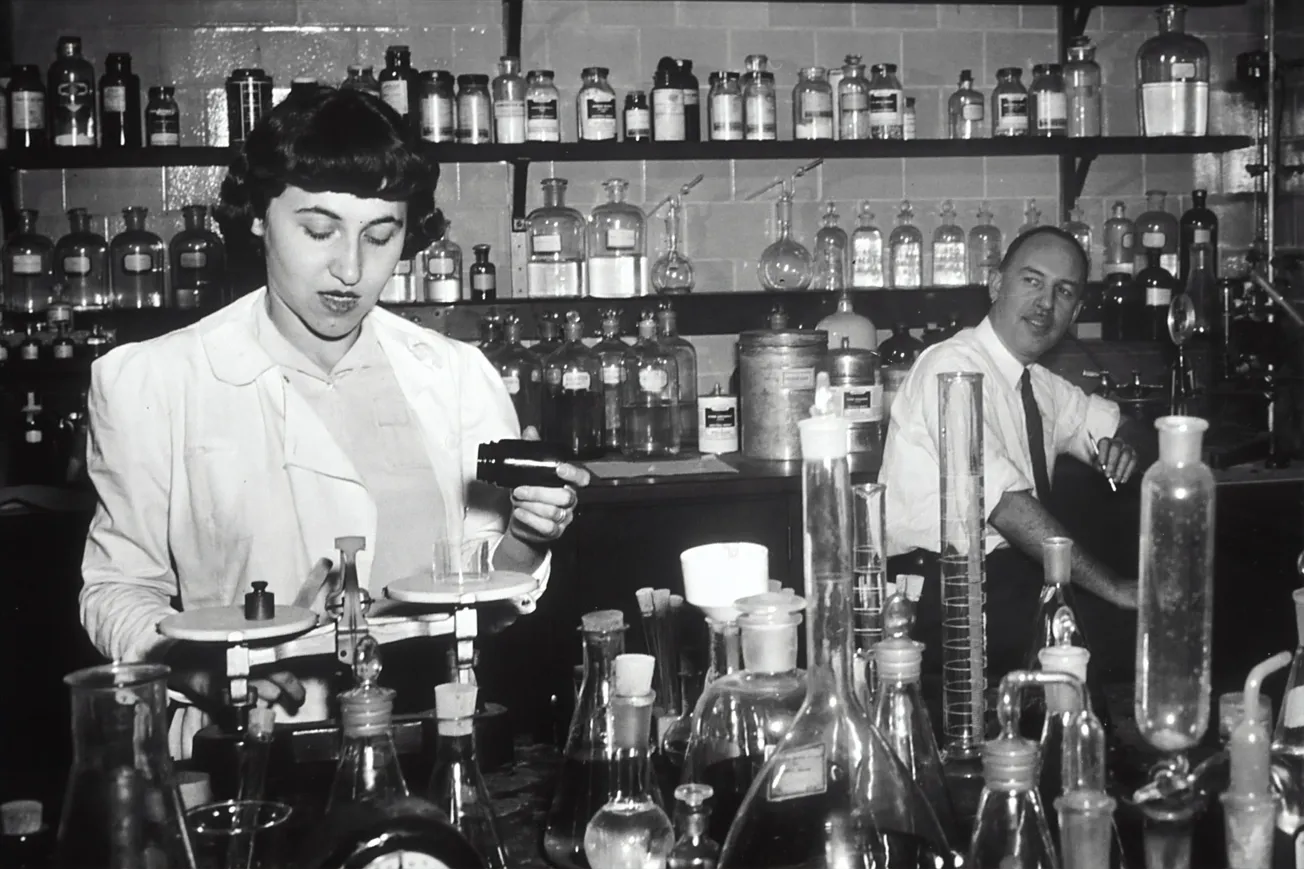

Cover photo: Dr. Jonathan Hartwell (right) and his assistant Sylvy R. Levy Kornberg conduct some of the earliest chemotherapy tests at the National Cancer Institute, about 1950. Photo credit: National Cancer Institute.