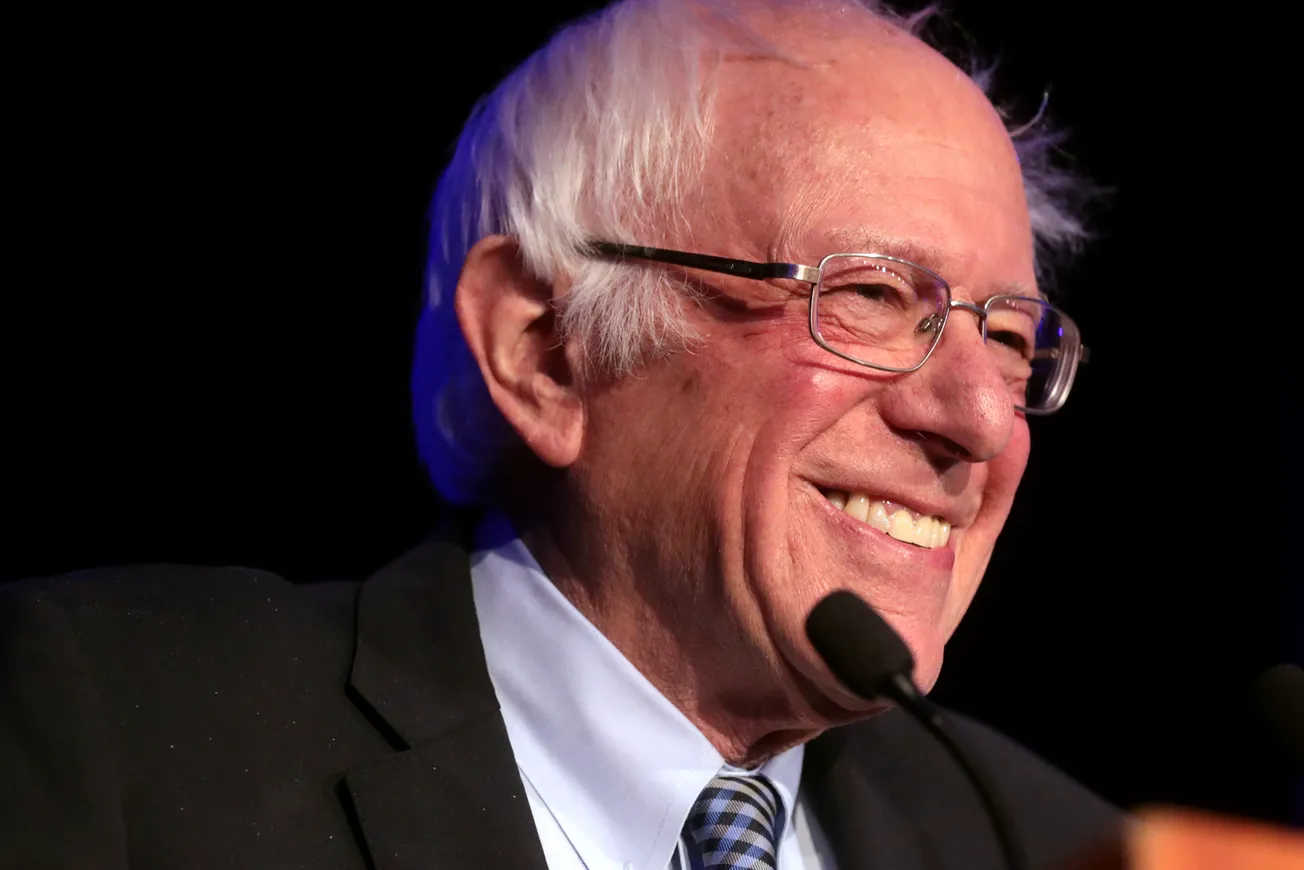

Vermont’s self-described socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders is a nonstop cheerleader for a minimum-wage hike. Recently, in Britain’s Guardian newspaper, he once again called for a huge increase in the minimum wage. Sounds generous, until you realize it would in fact hurt most the working poor, those who supposedly would reap the greatest benefits of a boosted minimum wage.

“Whether they are greeting us at Walmart, serving us hamburgers at McDonald’s, providing childcare for our kids or waiting on our table at a diner in rural America, there are too many Americans trying to survive and raise families on $9, $10 or $12 an hour,” Sanders wrote. “It cannot be done. This injustice must end. Low-income workers need a pay raise and the American people want them to get that raise.”

The idea that there are “too many” people “trying to survive and raise families on $9, $10 or $12 an hour” isn’t exactly true, at least not for the vast majority of workers.

Among the 76.1 million hourly wage workers, the average earner took home $33.18 an hour in March, or roughly $1,141.39 a week. That’s $59,352 a year. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ own data (for 2021, the latest full year for data) show that just 1.4% of all hourly workers made at or below the current minimum wage.

There’s a reason for this. Businesses pay people what they’re worth to them. If they can’t afford to pay you the going rate, they don’t hire you and you can try elsewhere. But, as the data show, businesses for the most part pay their workers well.

OK, but, as Sanders would have it, why not just have the government force businesses to pay the higher minimum wage for those at the bottom? Such as $17 an hour, his current proposal?

With ever-greater advances in labor-saving technology, machinery and, most notably, artificial intelligence, America will soon see large numbers of formerly employed people become unemployed.

Their jobs will become, in the British term, “redundant.” Sanders mentions McDonald’s in his remarks. Well, guess what? McDonald’s and other fast-food and retail outlets are already finding ways to cut employee costs through robots, self-checkout lines, and reductions in workers’ hours. Many small businesses are doing the same.

Unlike people, robots don’t call in sick. They work as long as they’re asked, get no benefits, can’t join a union. A self-checkout machine doesn’t take breaks or ask to go to the restroom (but, yes, they do malfunction now and then). And AI will soon be able to do many tasks that humans now do, including many highly paid ones.

At the same time, the lousy post-COVID economy is also a threat to all jobs, even those that pay well, thanks to inflation, rising interest rates and competition.

Just this week, Meta Platforms Inc. announced a second round of layoffs affecting nearly 10,000 workers, including “engineers and adjacent tech teams,” Reuters reported. That follows an earlier round of 11,000 layoffs.

Meanwhile, Disney revealed it will slash thousands of jobs at its entertainment division as soon as next week. When that happens, it won’t be the happiest place on Earth.

True, these people are not minimum wage-earners. But if even those privileged workers are losing their jobs, just how secure will the jobs be at the bottom end of the pay scale after a government-imposed 134% hike in the minimum wage?

Those most likely to hire low-paid workers are struggling right now. Small businesses employ roughly half of all workers, but make up nearly two-thirds of all job growth.

In a recent poll of small business owners, 63% said “they’re worried that the shaky economic environment could force their business to close — a six-point jump compared to February,” according to a press release from the Job Creators Network Foundation.

Whatever the minimum wage would be raised to — the last effort in 2021 boosted it to $15 an hour, but now Sanders wants $17 an hour — those under that new wage would be in serious jeopardy of losing their jobs entirely. No business pays workers more than the value of their overall productivity.

As Cato Institute senior fellow and economist Alan Reynolds noted during the union-backed “Fight for $15” debate three years ago, “every increase in the federal minimum wage in the past 40 years resulted in an average of a million more people being pushed into jobs paying below the federal minimum wage. Millions of tiny businesses are inescapably exempt from the law, as are many low-wage occupations.”

By the way, Reynolds adds that minimum wage hikes have a funny way of going into effect just before recessions — as they did “in 1969-70, 1974-75, 1980-81, 1990-91 and even 2007-2008.” Timing for a minimum wage hike, for the struggling poor, couldn’t be worse.

Sure, a big hike in minimum wage might not hurt low-wage workers as much in economically vibrant cities where labor demand is strong and prevailing local wages are already above $17 an hour. If so, why stop at $17 an hour? How about $50 an hour? $100 an hour?

The answer is obvious: It comes out of someone else’s pockets, not the government’s. And that someone is you.

So Sanders’ “minimum-wage hike” is really a “consumer tax hike.” That’s right. You’ll pay at the window of the drive-thru with much higher prices for all you buy. That’s another job killer.

Let’s be clear. We’re not against pay raises. However, the government forcing employers to pay workers more is the worst possible way to do the job. It ignores how strong or profitable a business is. It ignores current market conditions for individual firms. And it ignores basic supply and demand, both for labor and for goods and services. But worst of all, it ignores the inevitable tragedy of more working poor people losing their jobs.

— Written by the I&I Editorial Board

Original article link