The president of one of the most prestigious academic institutions in the world has resigned following an investigation into his research. Marc Tessier-Lavigne will resign as President of Stanford University at the end of August.

The move follows an external review of the prominent neuroscientist’s research work conducted by a panel of outside biologists and neuroscientists. According to the panel's report, "At various times when concerns with Dr. Tessier-Lavigne's papers emerged—in 2001, the early 2010s, 2015-2016, and March 2021—Dr. Tessier-Lavigne failed to decisively and forthrightly correct mistakes in the scientific record."

Though the panel did not find that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne had personally manipulated data, the report pointed out that he failed to correct the scientific record (published papers) even when presented with multiple opportunities.

Dr. Tessier-Lavigne's resignation letter stated, "I am gratified that the Panel concluded I did not engage in any fraud or falsification of scientific data." He will now likely retract or issue 'robust corrections' to at least five papers, one on Alzheimer's disease. Better late than never.

The 18-year-old Stanford Student Daily editor Theo Baker deserves credit for unraveling the scandal.

It is worth noting that billions are poured into labs and research facilities as funding and grants. The works of these scientists and researchers form the basis for other studies and innovations. Falsified data jeopardize further studies based on such research.

Data manipulation and falsification practices involve altering, omitting, or fabricating data (including images and other materials) to support desired conclusions, seriously eroding the reliability of research findings. While such incidents are atypical, there have been instances wherein well-known scientists were found to have engaged in unethical practices and been forced to retract their published works.

A couple of famous scandals come to mind. In 2014, a Japanese stem cell scientist, Dr. Haruko Obokata, groundbreaking paper on the creation of "Stap" cells (stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency) was retracted by Nature after repeated attempts failed to reproduce her results.

Decades earlier, in 1998, British physician, Andrew Wakefield, published a (now-debunked) study claiming a link between the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine and autism. The paper gained popularity before being retracted due to data manipulation and ethical violations. Though the physician lost his medical license, the damage had already been done.

Ironically, Francesca Gino, a prominent Harvard Business School professor who studies honesty, was alleged to have falsified data in a study on honesty!

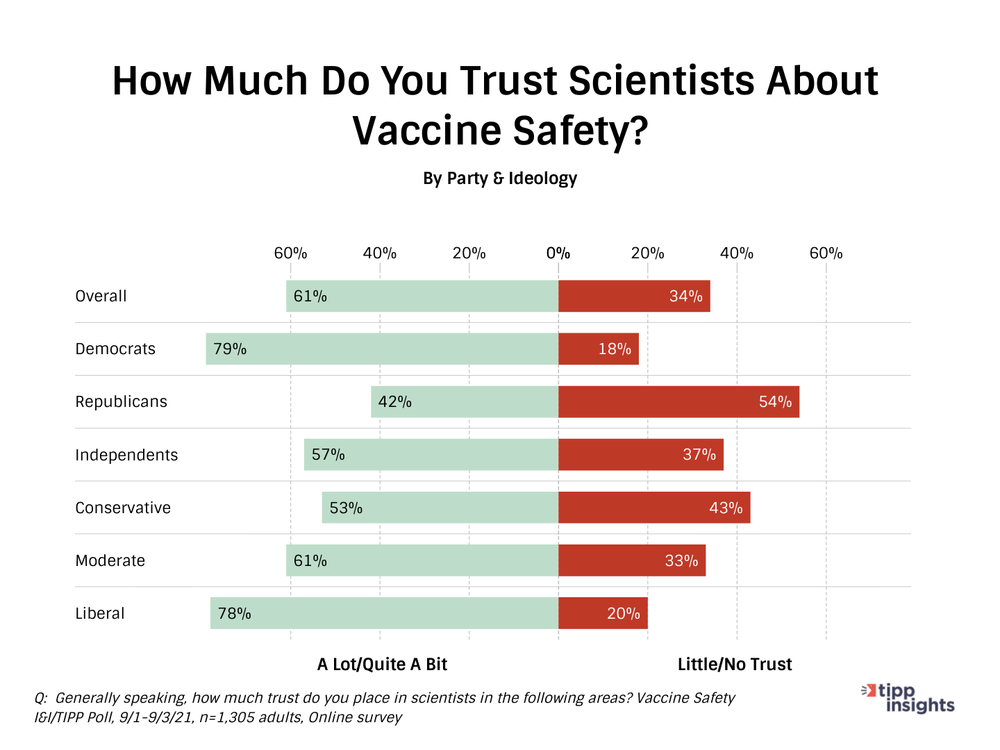

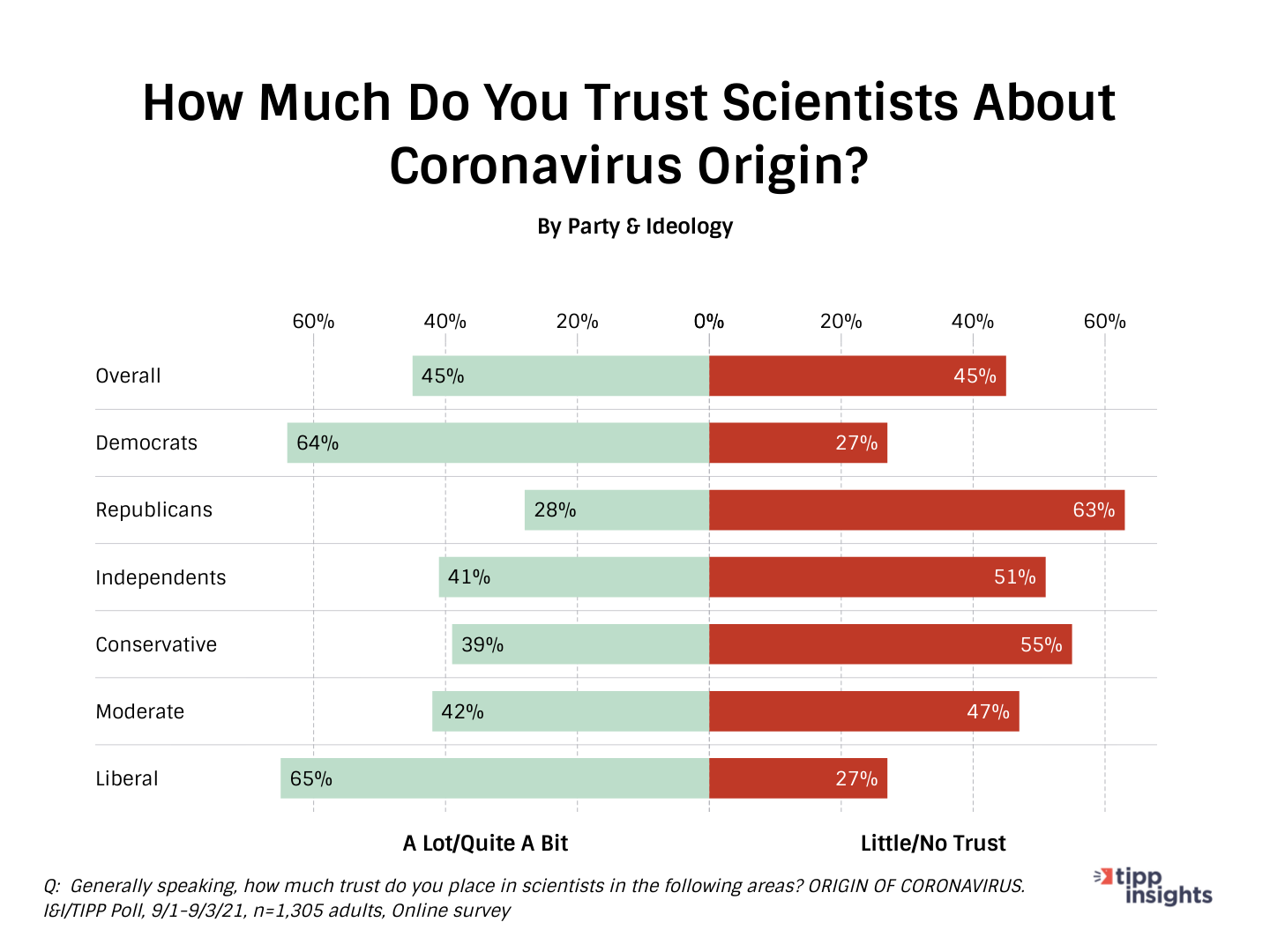

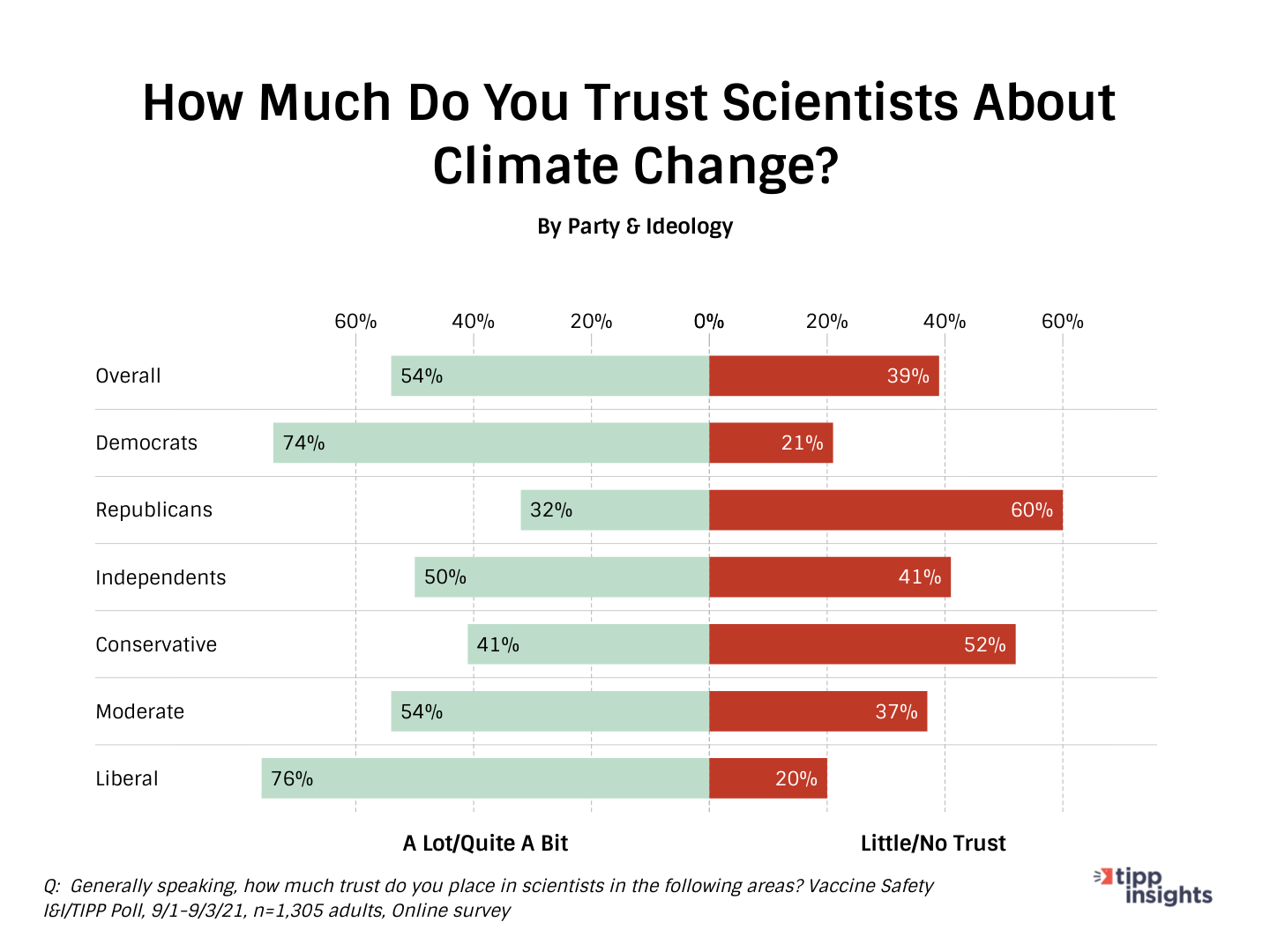

Such incidents, though rare, have eroded the public's trust in the research community. Big Pharma interference in medical research has gained much attention and is well documented. The skepticism about vaccines, pandemic protocols, and climate change continues to divide the country.

While the allegations of "manipulation of research data" and less than honest conduct may shock many outside the academia, it is unlikely to cause a seismic shock in the research world. The hallowed halls of these prestigious institutions offer a measure of insulation. Many renowned scientists and researchers have enjoyed successful careers despite similar scandals.

The Stanford neuroscientist is unlikely to face any other consequences. He was not let go following the report; he resigned. He will continue to be a tenured faculty member in the Department of Biology at the Ivy League University. It is unlikely that his grants will be revoked.

There are even those willing to share the blame. Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of the Science, which published two of the professor's papers in 2001, stated that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne had sent corrections to the publication, but they failed to run it. "It's certain to me that we're the ones that dropped the ball," Thorp said.

Beyond some short-lived embarrassment and notoriety, the incident is unlikely to significantly impact the scientific community or the research world. But, when such incidents come to light, the public is forced to wonder - whom to trust? What to believe?

Related Data

Like our insights? Show your support by becoming a paid subscriber!