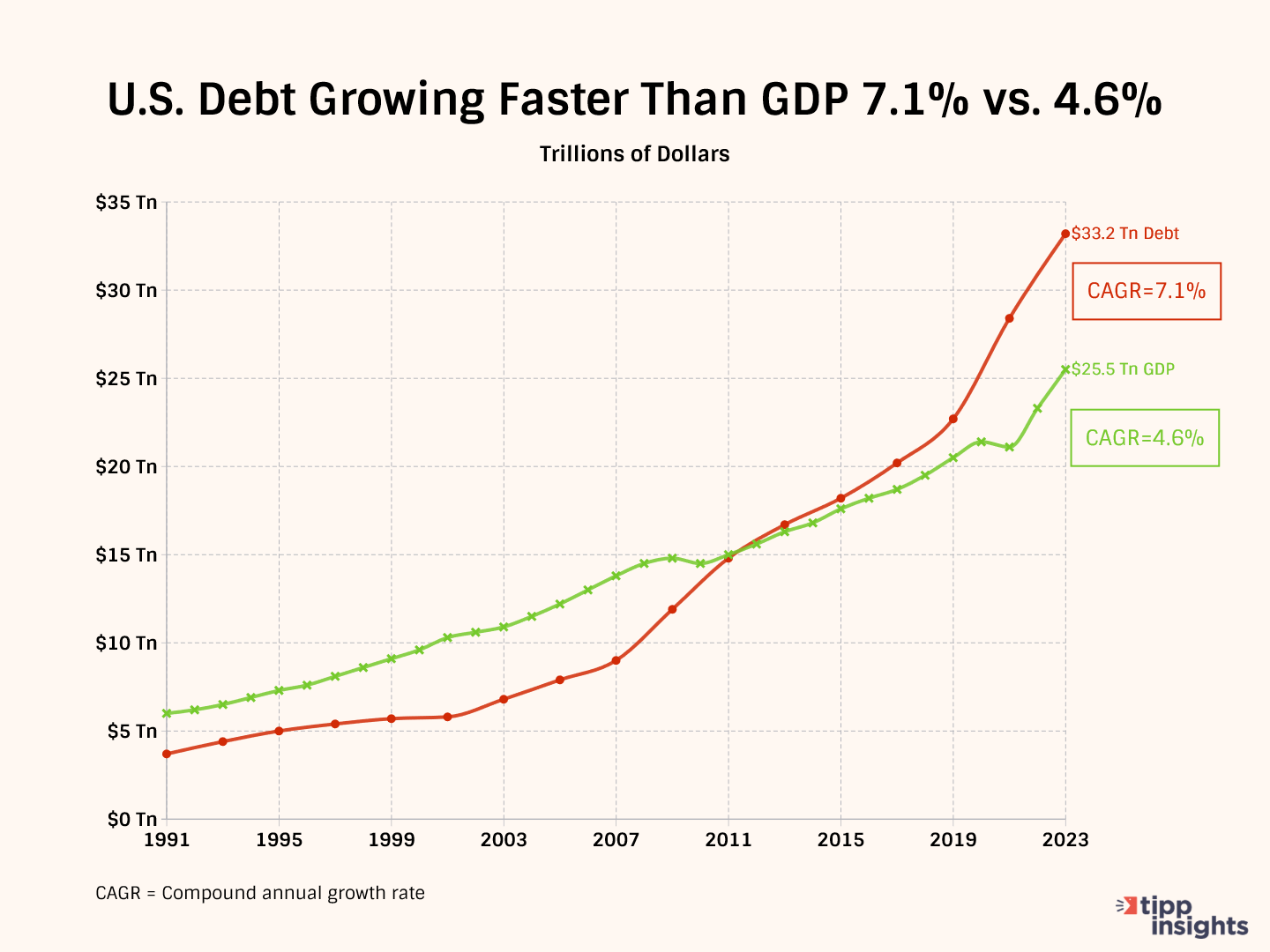

- America's total debt has reached an alarming level of over $34 trillion, exceeding 131% of annual GDP

- Unsustainable annual federal deficits, with the deficit approaching $2 trillion this fiscal year, raise concerns about fiscal responsibility

- The Federal Reserve's interest rate increases have substantially increased the cost of borrowing for the federal government

- Washington's failure to address federal deficits has led to the rise in interest rates and bond market instability

For all the Beltway politicians who continue to believe that deficit spending is acceptable if the cause is righteous, we ask them to read this.

The vitals of federal government spending - just like the vitals when a patient visits the doctor's office - can be summarized by a few metrics.

Dangerously rising debt to GDP ratio. Going back to America's founding, the total debt is about to reach $34 trillion, an unbelievably high number. America's Gross Domestic Product - the total value of goods and services - is expected to be about $25.9 trillion. So, America's total debt is more than 131% of annual GDP, a level not seen since World War II - and at current rates of federal borrowing, the debt to GDP ratio will only increase and worsen.

Unsustainable annual federal deficits. Last year, the Biden administration forecast an annual deficit of $1.15 trillion for fiscal 2023. It meant that the administration knew that revenues from taxes would be $1.15 trillion short compared to planned spending - and the difference would be all made up by borrowing. But thanks to the Federal Reserve, which has been increasing interest rates, the government has had to pay a lot more to service its debt. Also, allocating nearly $120 billion for the Ukraine war hurt. And to make matters worse, actual tax collections came in lower than forecast.

The government was estimated to take in $4.64 trillion in taxes but spent nearly $6.64 trillion. As a result, the annual deficit approached $2 trillion this fiscal year, a distressing increase. How is this sustainable?

While the above two are fiscal challenges (by fiscal, we mean tax, borrow, and spend policies), American monetary policy (governing the money supply and the value of the dollar), managed by the Federal Reserve Bank independent of the administration's priorities, has also played a crucial role.

The Fed's interest rate increases have caught everyone off guard. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve had spoiled consumers and the federal government through creative policies such as quantitative easing (by flooding markets with excess cash) and a concerted effort to keep interest rates near zero. As inflation spiked in 2021-22, the Fed finally acted.

On May 5, 2022, the Fed announced a 50 basis points increase in its Funds Rate to bring it into a target range of 0.75% to 1.00%. The Fed also began tightening its balance sheet, stopping its quantitative easing policy altogether, and asking borrowers to return cash to the Fed when their securities matured. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) met four times in the next six months - in June, July, September, and November. Each time, the Fed announced a 75 basis point increase, unprecedented in modern times. On November 3, the Fed Funds target rate reached 4%. This meant that the Fed had substantially increased the cost of borrowing for the federal government to service its ever-increasing debt. In December and February, the Fed again increased rates. Today, the Funds Rate stands at 5.33%. And Chairman Powell has not ruled out additional hikes.

Fed actions directly impact the federal government because the government has to pay the same interest rates to service its debt as everyone else. Besides, as the Fed has steadily shrunk its balance sheet, selling off whatever Treasury securities it had bought up during quantitative easing, there's a glut of Treasury bonds in the market. Such an oversupply means that the United States Treasury has to bribe investors by promising more returns as the government attempts to fund its priorities.

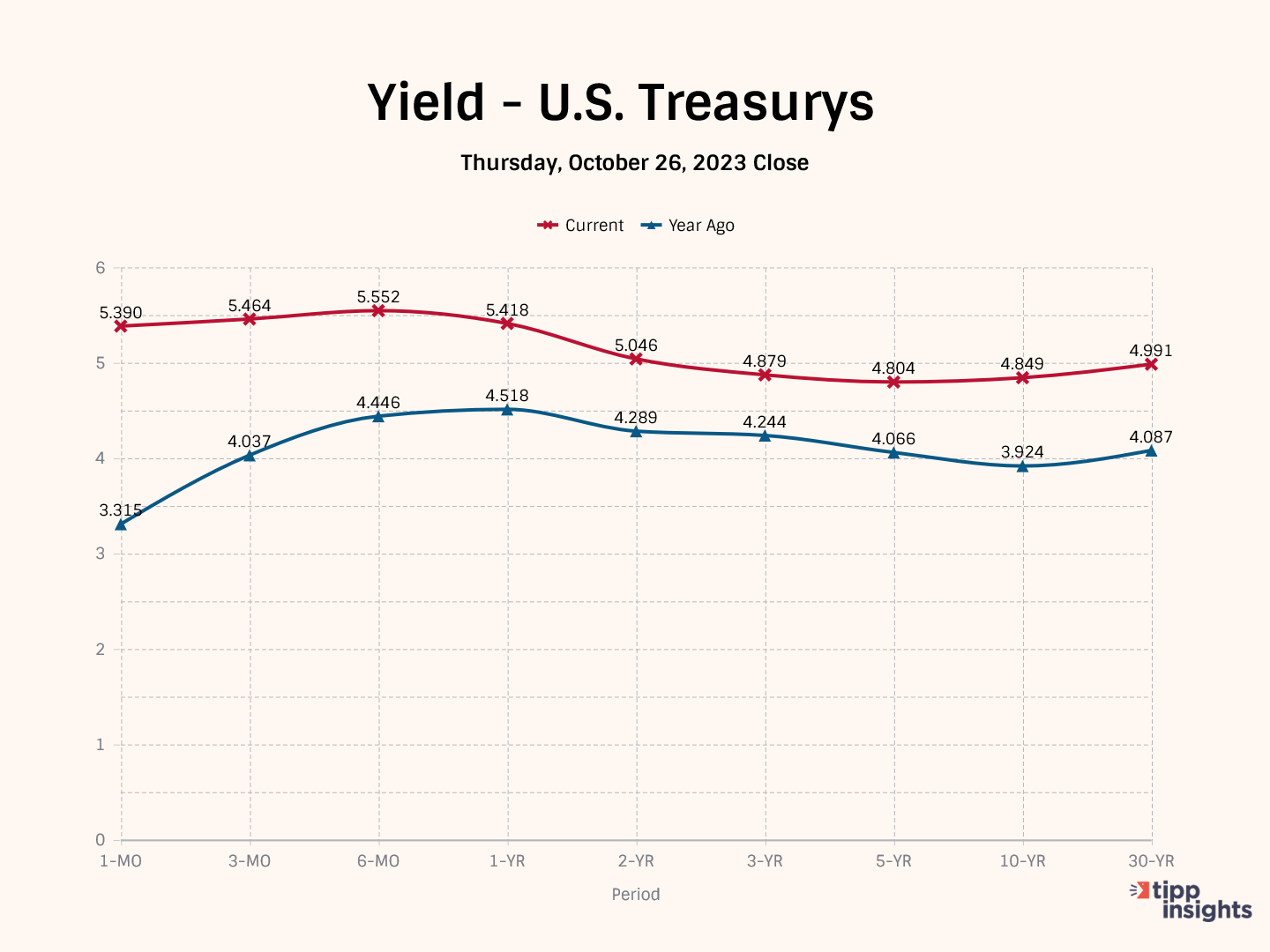

Chaos in bond markets. All of these factors bring us to the bond market, which, in dollar terms, is actually larger than the stock market. It is in the bond market where investors buy and sell U.S. Treasury bonds, corporate bonds, and other money instruments. Like any bank Certificate of Deposit, the two main things that matter are the bond's term (when the bond matures) and the interest rate.

The most common short-term bond is the 2-year Treasury note, which closely tracks the Fed Funds rate like any other short-term borrowing activity, such as credit card rates. Last week, Barrons reported that the U.S. Treasury Department auctioned $51 billion of two-year notes. But the demand was so soft that the department had to agree to higher interest rates of up to 5.05% to complete the sale..

Even more ominously, the yield on the 10-year Treasury bill, a longer-term instrument that does not track the Fed Funds rate, breached 5% last week, the first time since 2007.

A rule of bond markets is that when interest rates rise, bond prices fall - and vice versa. Someone who bought a 10-year Treasury bill in August at a certain price will have to see the same bond selling for less two months later, which is hardly a shout-out for a venerable cash instrument that holds value over time. The New York Times calculated that this indeed happened: "The most recently issued 10-year Treasury note from mid-August has already slumped nearly 10 percent in value since it was bought by investors." So disappointed is China, one of the world's largest holders of U.S. Treasurys, that the country has recently sold more than $45 billion in Treasury bills, slowly unwinding its positions rather than continuing to buy more Treasurys.

These changes in bond market behavior are unprecedented and can all be traced to one big culprit: Washington's reluctance to reign in federal deficits. But if you were to listen to our political leaders today, they are ready to spend an extra $106 billion, all freshly borrowed, to handle ‘national emergencies’ far away from American shores.

We could use your help. Support our independent journalism with your paid subscription to keep our mission going.