Hughes was an incredible human being. He was a fearless and famous aviator, a true entrepreneur, and a world-class eccentric. His father, a gifted engineer, started Hughes Tool Company, which became hugely profitable thanks to a patented rotary drill bit Hughes Sr. had developed for drilling oil wells. His dad passed when Howard was quite young, and he took over the running of the tool company and was already quite a wealthy man.

Always eager to try new things and armed with his money and drive, he entered the movie industry as a producer and director. He made waves in the film industry and was an innovator. He even developed a special bra for movie star Jane Russell to support some of her best assets. During his Hollywood years, he even dated Lauren Bacall, one of America’s sweethearts.

He loved aviation, and in 1938, he set a record for flying around the globe in just 91 hours and 14 minutes. A year later, he purchased a controlling interest in Trans World Airlines. He also developed the largest and most powerful wooden amphibious plane ever to fly (if only at 75 feet above the water for one mile) for the U.S. government. This lead to Hughes being charged by the government with war profiteering, as they had given the development contract in 1939, and he was being paid until the plane flew in 1947! He was visible, audacious, interesting, and talented.

Strangely, by the end of the 1950s, Hughes had become something of a germophobe and a recluse. People rarely saw him, but he continued to run his industrial and commercial empire from the privacy of his suite in The Desert Inn Casino and Resort, which he owned in Las Vegas. While the decisions he made still found their way into the news, no one actually saw him. But his companies still operated and were respected for their technical expertise.

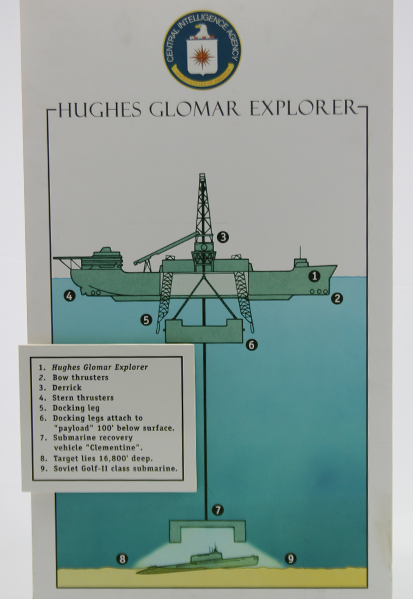

Hughes’s reputation for audacity and technical expertise made it seem perfectly natural that he would announce he was about to do something no one else had done before in early 1970. TV, radio, and newspapers worldwide carried stories about Howard Hughes building an incredibly advanced ship to harvest valuable rock known as manganese nodules or polymetallic nodules, which lay on the deep ocean floor. These nodules were composed of rare-earth metals, and while they were simply lying on the ocean floor, they were only found at depths below 4000 feet. While it seemed like an incredible mission, no one was particularly surprised when they saw Hughes was behind it.

A ship that would do this kind of work in the open ocean, far from land, attempting to do precision work at depths in excess of 4000 feet would need very advanced and precise navigation equipment, huge amounts of power to run maneuvering propellers, an incredible stability control systems, and giant winches to lower miles of cables and literally tons of tools to scour the ocean floor. The stories made great reading. Construction of the 350 million dollar ship began in August 1972. Two years later, while working in the Pacific Ocean, the Glomar Explorer’s real mission became clear when a front-page article appeared in the New York Times.

“CIA Salvage Ship Brought Up Part Of Soviet Sub Lost in 1968, Failed to Raise Atom Missiles”

That headline and the accompanying article by Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist Seymour Hersh blew the cover of the Glomar Explorer as a deep-sea mining vessel and made it pretty useless as a spy ship, as it was now the most famous ship on any ocean. The world was now aware that the engaging story of harvesting manganese nodules from the ocean floor was just a carefully concocted cover story. The Glomar Explorer was never designed to harvest rare earth elements, but rather a Russian submarine armed with nuclear missiles that had gone missing in 1968. The Glomar Explorer had managed to raise part of that submarine, but it had failed to recover any of its nuclear missiles. Howard Hughes offered no comments, but without his name, the cover story could never have existed.

In 1976 the Hughes Glomar Explorer was put into mothballs, its career suspended, but not over. Just over 20 years, and one major retrofit later, the famous ship went to sea again, this time as an actual deepwater drilling ship for major oil companies. In its first year of commercial operation, the former spy vessel successfully “spudded” a well almost 8,000 below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico. Over the next 17 years, the ship traveled to deep water sites around the world, drilling wells; off the shores of Angola, Malaysia, Malta, Singapore, and the Black Sea.

After a record-setting career as a technically advanced deepwater drilling ship, Glomar Explorer was acquired by the world’s largest offshore drilling contractor, who renamed her GSF Explorer.

By the end of 2014, now almost 40 years old, the most famous, most storied, largest, and most advanced deepwater drilling vessel was sold for scrap. And, where was she sent to be taken apart piece by piece? Funny, you should ask. Why China, of course!

You might be asking yourself one more question. If Howard Hughes and the CIA were kind enough to give us the blueprints for recovering manganese nodules composed of rare earth elements from the deep ocean floor back in the early 1970s, why has no one bothered to go collect them until now?

The answer is economics. Until there was a robust and growing market for the rare earth metals extracted from these nodules, it simply did not make economic sense to harvest them. The problems inherent with deep-sea recovery in the open ocean still exist, so it will never be an inexpensive process. But, thanks to the dramatic increase in demand for metals like cobalt, copper, manganese, nickel, and lithium for use in batteries for electronic devices, cordless power tools, and the approaching exponential growth for batteries in electric vehicles, the economic picture is now much more attractive than ever before. Howard Hughes would be proud.

Will harvesting manganese nodules from the ocean floor ever be a practical reality? Economically it looks to be way more practical than it would have been decades ago. Also, since the time of the Glomar Explorer, there have been more laws passed governing activities on the ocean floor. And there are new governing bodies that need to evaluate the environmental impact on sea life, the ocean floor, and the ocean itself. The Metals Company, the British-based organization aiming to make the cover story of the Glomar Explorer a reality, still has its work cut out for them. To learn more about their objectives and challenges, visit Metals Company.