For more than 33 years since the end of the Cold War, two identities on the European continent have been essentially in sync. There has always been NATO, going back to 1949, a predominantly defensive alliance that acted as a bulwark against Soviet aggression and the spread of Communism- both risks that were prevalent throughout the Cold War. In the last 25 years or so since the launch of the Euro, the European Union, as a bold experiment in integrating countries into a common bloc, Soviet-style, has more or less succeeded.

Since the Biden-Harris administration was sworn in, the NATO alliance has thrived, thanks to unfettered support from the United States- something that may not continue when the new Trump administration takes over. However, thanks to the Biden foreign policy team's lack of foresight, the move has come at a severe cost to the EU's economic and geopolitical stability.

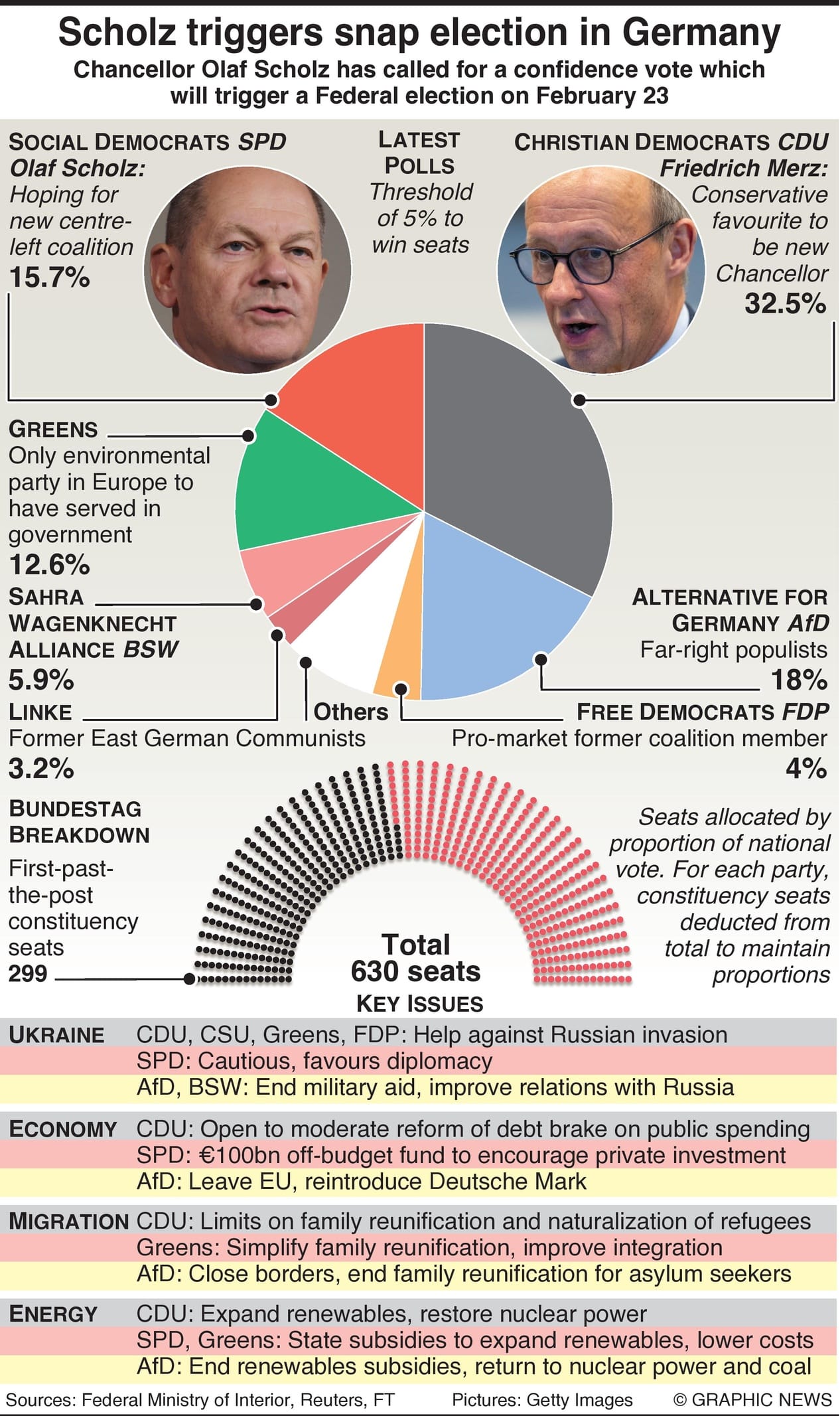

The latest victim is Germany, whose leader, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, lost a vote of confidence in the German parliament, where 394 members voted no, 207 voted yes, and 116 abstained. Scholz needed 367 yes votes to survive.

In neighboring France, lawmakers passed a no-confidence measure against Prime Minister Michel Barnier and his cabinet just two weeks ago. President Macron's hand-picked leader needed 288 votes, but the margin of defeat was 43 votes, as 331 parliamentarians voted against the Prime Minister.

The votes expressed profound dissatisfaction with the political leadership in the two countries, and if the trend holds, the ruling parties are likely to suffer significant defeats in upcoming elections.

Initially, the concept of European Union integration made sense. If countries were contributing to the NATO alliance, it would make sense to have an economic partnership as well. Despite numerous cultural differences – and the fact that many of the EU countries were colonial powers with proud histories and legacies to defend- the European Union actually came into being. It was the ultimate formulation of the so-called rules-based international order, because only rules could govern such a diversity of traditions.

Then came the launch of the Euro as a competitor currency to the United States dollar. This milestone was especially problematic as proud countries had to give up their Deutschmarks, French francs, and Dutch Gilders to support a common currency. When the final piece of EU architecture was in place, it was unlike anything the world had ever seen.

The European Union Central Bank would dictate that the Bloc's monetary policy (interest rates, value of the Euro) be standard across all member countries. However, the fiscal policy was left to the individual states, meaning that taxes collected, expenditures, deficits, and debt were independently managed at each state capital, albeit under broad EU guidelines.

During the 2008 financial crisis, the PIIGS countries (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) almost ended the nascent EU experiment. Each country had amassed unsustainable public and private debt and could only survive after massive cash injections from the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Economic reforms imposed by creditors led to public dissatisfaction, political instability, and social unrest. Because wealthy economies like Germany and France were relatively healthy, the PIIGS countries survived- with a bailout.

Today, Germany and France are in deep trouble. Voters are upset at the high cost of living and the lack of economic growth. People are also beginning to question the wisdom of their countries sending billions of dollars to Ukraine when their citizens are suffering. Voters are also protesting the shipment of lethal weapons to Ukraine that allows Kyiv to attack Russia. War fatigue has set in, and voters want peace. [In Romania, when voters chose a presidential candidate who advocated for peace talks in the Russia-Ukraine war, a Constitutional Court annulled the election, saying that Russian interference tainted the election].

Germany's and France's economic growth problems are a direct result of the Biden administration's policy. Since 1991, Russia, with its abundant natural resources- including oil, natural gas, chemicals, and coal- had been supplying them at very low cost to industries in Germany and France. However, the Biden administration convinced EU member states to abandon the economic integration that had developed with Russia for nearly 20 years, from 1995 to 2014, and to sanction Russian energy supplies. For every request from Washington to sanction Russia, the EU members merrily went along and stopped selling to Russian customers, yielding market share to China and other countries.

The result was immediate. The EU's mega factories faced a severe energy shortage, forcing many to idle. The Bloc's infrastructure had to be retooled to accept energy from new Liquefied Natural Gas terminals.

When the factories were finally operational, relying on expensive energy from the United States and other nations (powered by LNG), EU companies' products were no longer competitive in world markets. They began to lose business to Chinese, Korean, and Japanese producers.

Germany, in particular, has seen its auto industry, a cornerstone of its economy, suffer irreversible consequences. As manufacturing costs rose, the country's automakers, slow to embrace electric vehicles, have steadily lost business to Chinese and American competitors. Volkswagen, the country's largest employer with an 87-year history, announced - for the first time - that it planned to shut at least three factories in Germany, lay off tens of thousands of staff, and shrink its remaining plants . The German economy continues to be in a recession.

Jana Puglierin of the European Council on Foreign Relations told the New York Times: "The timing is absolutely terrible for the EU — basically, these multiple crises are hitting the EU at the worst possible time because the bloc's traditional engine is busy with itself."

The Biden-Harris foreign policy team will be gone in about a month, but the EU's problems will remain.