By Yi Fuxian, Project Syndicate | Jan 20, 2026

After decades of the one-child policy, the decline in China's fertility rate was inevitable, like a boulder rolling down a hill. With the problem now being compounded by numerous other factors, pushing the boulder back uphill will be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, and will not happen quickly.

MADISON – China has just announced that births in 2025 plunged to 7.92 million, from 9.54 million the previous year – and almost half of what was projected (14.33 million) when the one-child policy was repealed in 2016. In fact, China’s births have fallen to a level comparable to that of 1738, when the country’s total population was only about 150 million.

Having finally acknowledged the country’s grim demographic reality, Chinese authorities introduced new pro-natalist policies last year, expecting the number of births to rebound. But the decline in the fertility rate was inevitable, like a boulder rolling down a hill. Even if it can be pushed back uphill, it will not happen quickly.

After all, the downward trend in marriages will be difficult to reverse, since the number of women aged 20-34 – the group responsible for 85% of Chinese births – is expected to drop from 105 million in 2025 to 58 million by 2050. Compounding the problem, China’s marriage market suffers from a pronounced mismatch. Decades of sex-selective abortion have created a severe shortage of women of childbearing age, and women’s higher educational attainment has created a “leftover women” phenomenon, with female students outnumbering males. Whereas the male-to-female ratio among six-year-olds in 2010 was 119:100, by 2022, when this cohort entered college, the ratio in undergraduate admissions was only 59:100. As a result, more men are unable to find wives, and more women are likely to remain unmarried, given their preference for more highly educated husbands.

China’s current policies are a scaled-down version of Japan’s ineffective response to demographic decline. In Japan, fertility fell from 1.45 (far below the replacement rate of 2.1) in 2015 to 1.15 in 2024. With China facing even deeper structural demographic constraints, it is not surprising that its fertility rate has already fallen below Japan’s.

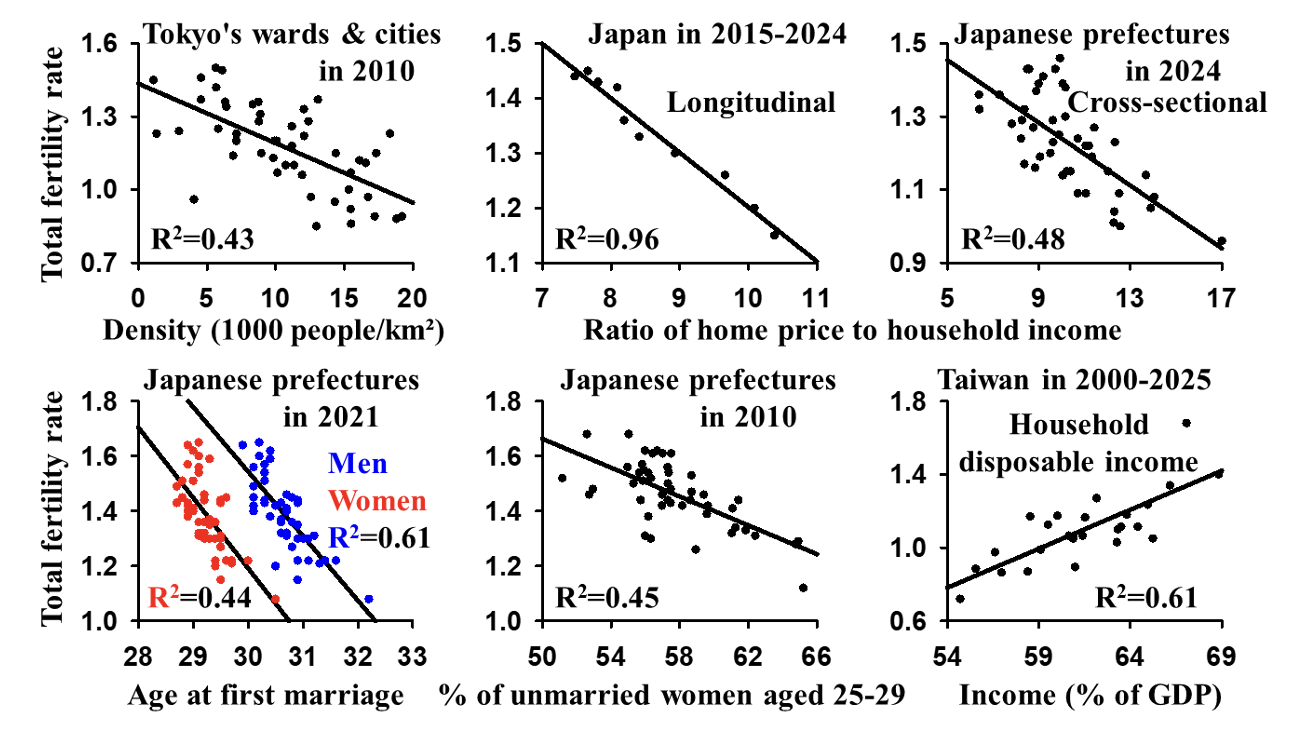

It is an ecological law that density inhibits the growth of bacteria, plants, and animal populations, and humans are no exception. Across wards and cities in Tokyo, population density is negatively correlated with fertility rates, and the same pattern can be found in London, New York, and Shanghai. Built-up urban areas in the United States typically have 800-2,000 people per square kilometer, compared to about 6,000/km² in Tokyo. In China, the average is 8,900/km², with many districts in first- and second-tier cities – where young people flock – often reaching 20,000-30,000/km².

High population density drives up housing costs, and higher price-to-income ratios negatively affect fertility. In recent years, declining fertility in Canada, the US, and European countries has been partly driven by soaring housing prices. Since China’s price-to-income ratio far exceeds Japan’s, and since its housing bubble is much larger, boosting fertility would require transforming (demolishing and rebuilding) its cities to lower their population density and housing costs. Doing that, however, could trigger a financial crisis or even an economic collapse.

Japan’s experience also shows that the average age for men and women at first marriage is negatively correlated with fertility, as is the proportion of unmarried women aged 25-29. In China, the average age at first marriage rose from 26 for men and 24 for women in 2010 to 29 and 28, respectively, in 2020. Worse, the share of unmarried women aged 25-29 surged from 9% in 2000 to 33% in 2020, and to 43% in 2023.

The Chinese government has introduced a “new quality productive forces” policy to offset the drag of aging on the economy. But such pro-growth measures will inevitably prolong education, which will delay marriage and childbearing, increase the proportion of unmarried individuals, and lower fertility further.

Again, Japan shows that there are no easy solutions. It funded childbirth subsidies by raising the consumption tax. But as the saying goes, the wool comes from the sheep: the burden ultimately fell on households, reducing disposable income as a share of GDP, which has fallen from 62% in 1994 to 55% in 2024 – a loss that subsidies can scarcely offset. Similarly, Taiwan’s fertility rate fell from 1.68 in 2000 to 0.72 in 2025, partly reflecting the decline in household disposable income from 67% of GDP to 55%. In mainland China, household disposable income already accounts for only 43% of GDP, making child-rearing even more difficult.

China’s best option to increase fertility would be to raise its household income share, which would also boost consumption and absorb excess capacity. But the government is unlikely to pursue such a paradigm shift, because doing so could weaken its own finances and power, potentially reshaping China’s political landscape.

Moreover, even if China could afford to increase fertility by providing generous social benefits, the effects would not last, because such interventions risk weakening family structures and reducing male labor-force participation. After Nordic countries adopted similar policies, the proportion of children born out of wedlock surged to 50-70%, with taxpayers serving as “public fathers” and the “public children” supporting the elderly.

This collectivist model – itself reminiscent of China’s Great Leap Forward (1959-62), which led to tens of millions of deaths from famine – is unsustainable. In Finland, the fastest aging of the Nordic countries, the fertility rate fell from 1.87 in 2010 to 1.25 in 2024; and in Sweden, it has dropped from 1.85 in 2016 to 1.43 in 2024, reflecting the tension between elderly welfare and the survival of the unborn.

The strength of a chain is determined by its weakest link, and in China’s case, several links need strengthening. Fertility can rise only if China addresses them all. With many countries in need of viable solutions to low fertility and population aging, one hopes that it can set an example that does not violate human rights. But other countries’ experience suggests that no one has yet figured out how to make boulders roll uphill.

Yi Fuxian, a senior scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, spearheaded the movement against China’s one-child policy. His book Big Country with an Empty Nest (China Development Press, 2013), initially banned, now ranks first in China Publishing Today’s 100 Best Books of 2013 in China.

Copyright Project Syndicate

👉 Quick Reads

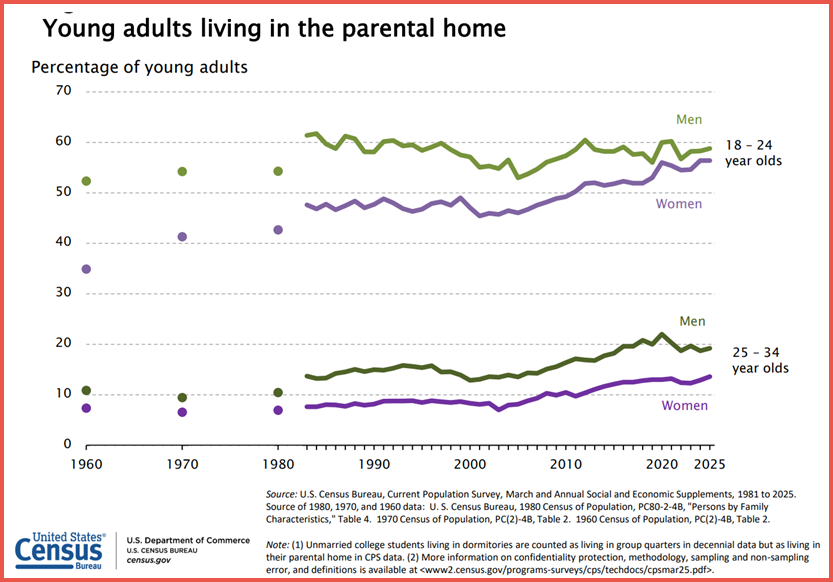

I. More Young Adults Are Staying In The Parental Home

The share of young adults living with their parents has risen sharply since the mid-2000s, especially after the 2008 financial crisis. The trend is strongest among ages 18–24 and is also rising among those 25–34, with men consistently more likely than women to live at home. Recent years mark the highest levels on record, reflecting higher housing costs, longer time in education, and tougher entry into the job market.

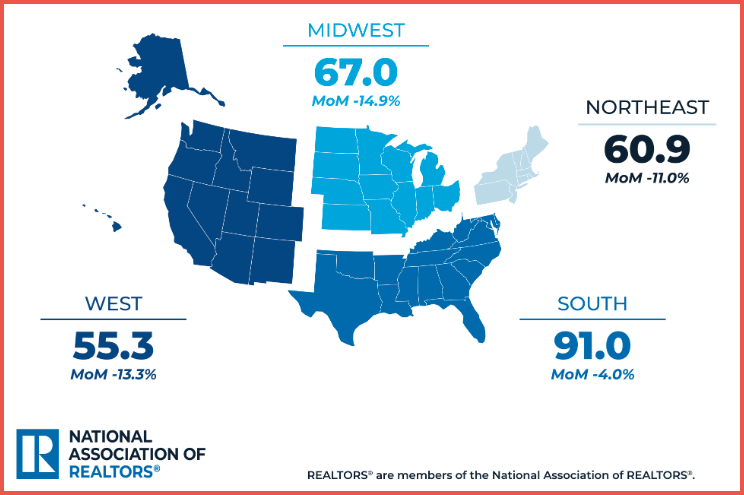

II. Pending Home Sales Slide Nationwide

Pending home sales—homes that are under contract but not yet closed—fell sharply in December, the largest monthly drop since the COVID shock. Because pending sales are a leading indicator, this suggests closed sales are likely to weaken in coming months. The slowdown was broad across the Midwest, Northeast, and West, while the South saw a smaller decline and remains the strongest region overall.

📊 Market Mood — Thursday, January 22, 2026

🟩 Risk-On Relief as Greenland Fears Ease

U.S. futures rally after President Trump outlined a framework deal on Greenland, pulling back tariff threats against Europe and calming geopolitical nerves.

🟦 Earnings Take Center Stage

With geopolitics cooling, attention shifts to heavyweights including Intel, Procter & Gamble, GE Aerospace, and Abbott, as earnings season gathers momentum.

🟨 Fed & Data in the Background

Markets await key U.S. data — jobless claims, GDP, and PCE inflation — ahead of an expected Fed pause, with policy pressure from the White House still lingering.

🟥 Safe Havens Cool Off

Gold retreats from record highs and oil slips as risk appetite improves and U.S. crude inventories rise, easing near-term supply concerns.

🗓️ Key Economic Events — Thursday, January 22, 2026

🟧 08:30 AM — U.S. GDP (QoQ, Q3)

Measures overall economic growth in the prior quarter; backward-looking but useful for confirming momentum trends.

🟨 08:30 AM — Initial Jobless Claims

Weekly snapshot of layoffs and labor-market tightness, closely watched for signs of cooling employment.

🟦 10:00 AM — Core PCE Price Index (MoM & YoY, Nov)

The Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, stripping out food and energy; critical for rate-cut expectations.

🟩 12:00 PM — Crude Oil Inventories

Tracks changes in U.S. oil stockpiles, influencing energy prices and inflation expectations.

editor-tippinsights@technometrica.com