By Farrell Gregory, CFACT |December 29, 2024

America has a mineral security problem. The materials and resources that power essential and next-generation technologies increasingly come from abroad. Our supply chains – formed in the post-Cold War period of free trade expansionism – have become vulnerabilities in our modern age of multipolarity and great power competition. Now, America’s capacity to build and innovate relies on the goodwill of our competitors. Without secure supply chains for critical materials, our essential defense and commercial industries will remain vulnerable.

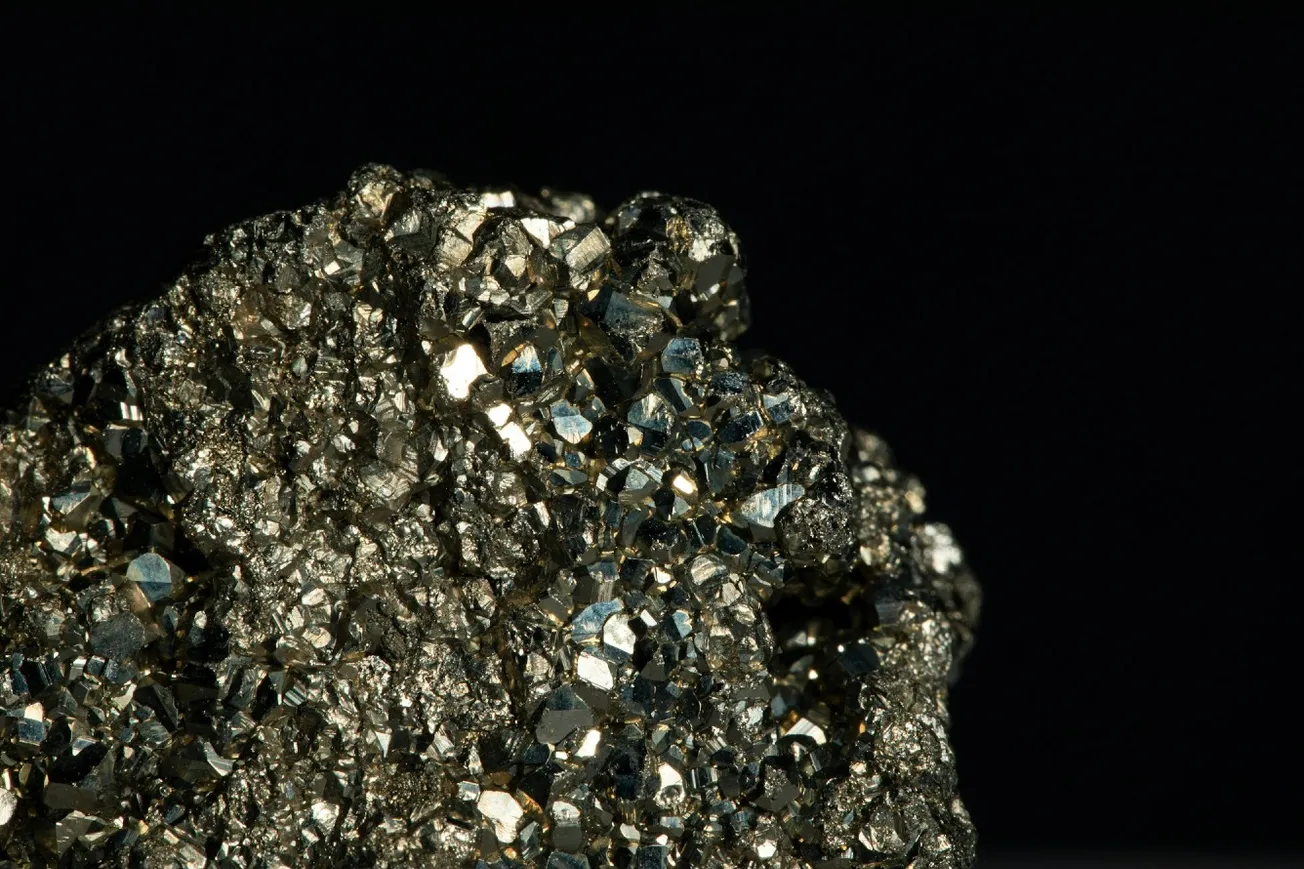

That vulnerability is already being exploited. On August 14, China announced export restrictions on a critical mineral called antimony, which has essential applications in munitions, technologies like night vision goggles and sensors, and batteries. On December 3rd, China’s Ministry of Commerce expanded that ban to include gallium and germanium while tightening controls on graphite. This is particularly concerning for the U.S. – 63% of antimony imports, 50% of gallium and germanium imports, and 30% of graphite imports, come from the People’s Republic of China. The supply cut will likely inflate the price of these minerals and leave buyers in the U.S. scrambling to meet their needs.

But America doesn’t need to be as susceptible to foreign supply shocks as we are. In the past, our defense industrial base and commercial mining industry furnished a wide array of resource needs, insulating American industry from threats abroad. The case of antimony is a particularly striking example of how much ground the U.S. has ceded in mineral security.

Although not nearly as large as other producers like China and Russia, the U.S. does have some domestic antimony deposits – particularly in mountainous Western states and Alaska. During World War II, American suppliers such as the Stibnite mine in Idaho met 90% of domestic antimony needs and made a substantial contribution to the war effort. According to the 1956 U.S. Senate Congressional Record, the output of the mine was credited with hastening the end of the war and saving the lives of America soldiers. But, according to an August 2024 CSIS report, as environmental legislation “tightened in the 1970s, domestic antimony production declined.” Today, the U.S. doesn’t mine any antimony, with our last mine shuttering in 2001. While the U.S. does fulfill some of its antimony needs through recycling, our diminished domestic mining capacity has left us reliant on imports and vulnerable to the export controls on antimony imposed by China.

It doesn’t have to be this way. America has ample domestic deposits of critical minerals – but over-burdensome and impossibly complex regulations like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 are partially responsible for our current security crisis. First, laws like NEPA raised the time and capital costs of building and maintaining a domestic mining industry – as demonstrated in the case of antimony. And now, when the U.S. needs to access its domestic reserves in the face of supply shocks abroad, NEPA slows down the pace of development to an untenable and slow pace that threatens national security.

Take, for example, Perpetua Resources’ plan to reopen the Stibnite Mine – which, despite contributing so much to industrial base needs in World War II, ceased operations in the 1990s. Beginning initial study and engineering in 2010, Perpetua has been locked in onerous NEPA proceedings since 2016. Eight years later, in September 2024, the U.S. Forest Service had only then completed its Final Environmental Impact Statement and issued a Draft Record of Decision, authorizing the mine. But even now, NEPA requires that the project undergo a 45-day objection period and subsequent 45-day resolution period before issuing a final Record of Decision.

The most concerning part of this permitting process is that the Perpetua Stibnite Mine project isn’t an aberration – it’s the norm. Permitting for mining projects can take up to ten years on average. In comparison, permits from Canada and Australia take between two and three years. The NEPA permitting process, as it stands, will continue to obstruct efforts to revitalize America’s domestic mining industry and achieve mineral security. To avoid this bleak future, NEPA and its state-level equivalents need reform. The good news is that Congress and state legislatures across the country don’t need to choose between environmental protection and development in the name of national security. Instead, common sense reforms can unburden domestic miners without compromising our natural resources.

In recent weeks, the future of NEPA’s rulemaking authority has come under judicial scrutiny. In Marin Audubon Society v. Federal Aviation Administration, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled that the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) lacked statutory authority to issue binding rules under NEPA. After the Manchin-Barrasso permitting reform bill fell apart this week, it is clear that reform at the federal level will have to wait until the 119th Congress.

But while the CEQ decision and a NEPA bill are litigated in DC, permitting reform remains necessary and possible at the state level. A State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) is typically modeled off of the federal law, adding regulatory burden to state activities and typically triggering a time-intensive process of environmental impact review. The Foundation for American Innovation’s recently published State Permitting Playbook offers state-by-state analysis and reforms for permitting regulations. Short of a full repeal, there are many options for state legislatures to loosen their SEPA regulations: raising the threshold for environmental impact studies, limiting standing for challenging SEPA decisions, and creating permitting exemptions for projects essential to national security, such as mines for critical minerals. Although Idaho, the site of the Stibnite mine, has no SEPA, neighboring Montana has one of the country’s most stringent state-level environmental policy laws. Montana’s SEPA takes an average of 15 months to complete review for mines – permitting reform in the Treasure State would unlock its abundant natural resources to lessen America’s critical mineral vulnerabilities.

While the future of CEQ’s regulatory authority is adjudicated in the courts, reforming SEPAs could ease the burden of domestic miners. Of course, state-level reform wouldn’t eliminate America’s foreign mineral dependence. When fully operational by 2028, the Stibnite mine is expected to meet about only one third of America’s domestic antimony needs. But few public policy issues have simple solutions. NEPA and state-by-state SEPA reform would lower the barriers to domestic production and refinement of a whole range of critical minerals. The U.S. will always be reliant on foreign sources of minerals to some degree – but improvement comes incrementally. The key to reducing our vulnerability abroad and unlocking our mining potential is regulatory reform. By finding solutions that protect the environment and unleash our domestic industry, the U.S. will take the first step towards greater supply chain security.

This article originally appeared at Real Clear Energy

Farrell Gregory is research assistant at the Yorktown Institute and chief editor of the Emerging Threats Journal. He is currently a visiting student at Mansfield College, Oxford, studying politics, philosophy, and economics.

Original article link