Late in 2021, a fierce Twitter clash erupted between Senator Elizabeth Warren and Tesla CEO Elon Musk. Warren taunted Musk, saying the world’s richest person was a freeloader who had paid no income taxes in recent years. Musk responded by referring to Warren as "Senator Karen" and asserting that his upcoming income tax bill would be the largest in U.S. history. Musk paid about $11 billion in taxes for 2021.

Behind the exchange is the issue of unrealized capital gains. Progressive politicians, such as Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), are big supporters of a wealth tax on unrealized capital gains. They argue that such a tax would ensure the wealthiest individuals pay their fair share and help reduce economic disparities.

Grasping the concept of unrealized capital gains is pivotal to understanding this debate. This term refers to the increase in the value of an asset you haven't sold yet. For example, if you bought stocks for $100,000 a few years ago and their current appreciated value is $150,000, your unrealized gain is $50,000. Only when you sell the stocks and receive the money can you realize this gain. As long as you hold the stocks, the gain remains unrealized, a key point in the wealth tax debate.

The Supreme Court's ruling on Thursday in the Moore tax case reaffirmed the constitutionality of the mandatory repatriation tax (MRT) introduced by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Even if they do not receive the foreign corporation's income, the MRT mandates that American shareholders pay taxes on it. Charles and Kathleen Moore owned a stake in an Indian company but did not receive dividends or income from their investment. Because of the MRT, the Moores paid about $15,000 in taxes on earnings attributed to them as shareholders. They argued that the tax was unconstitutional because it taxed unrealized income, but the court upheld it as constitutional. The ruling is considered narrow, applying specifically to taxing undistributed income from foreign corporations rather than directly addressing broader issues of unrealized capital gains.

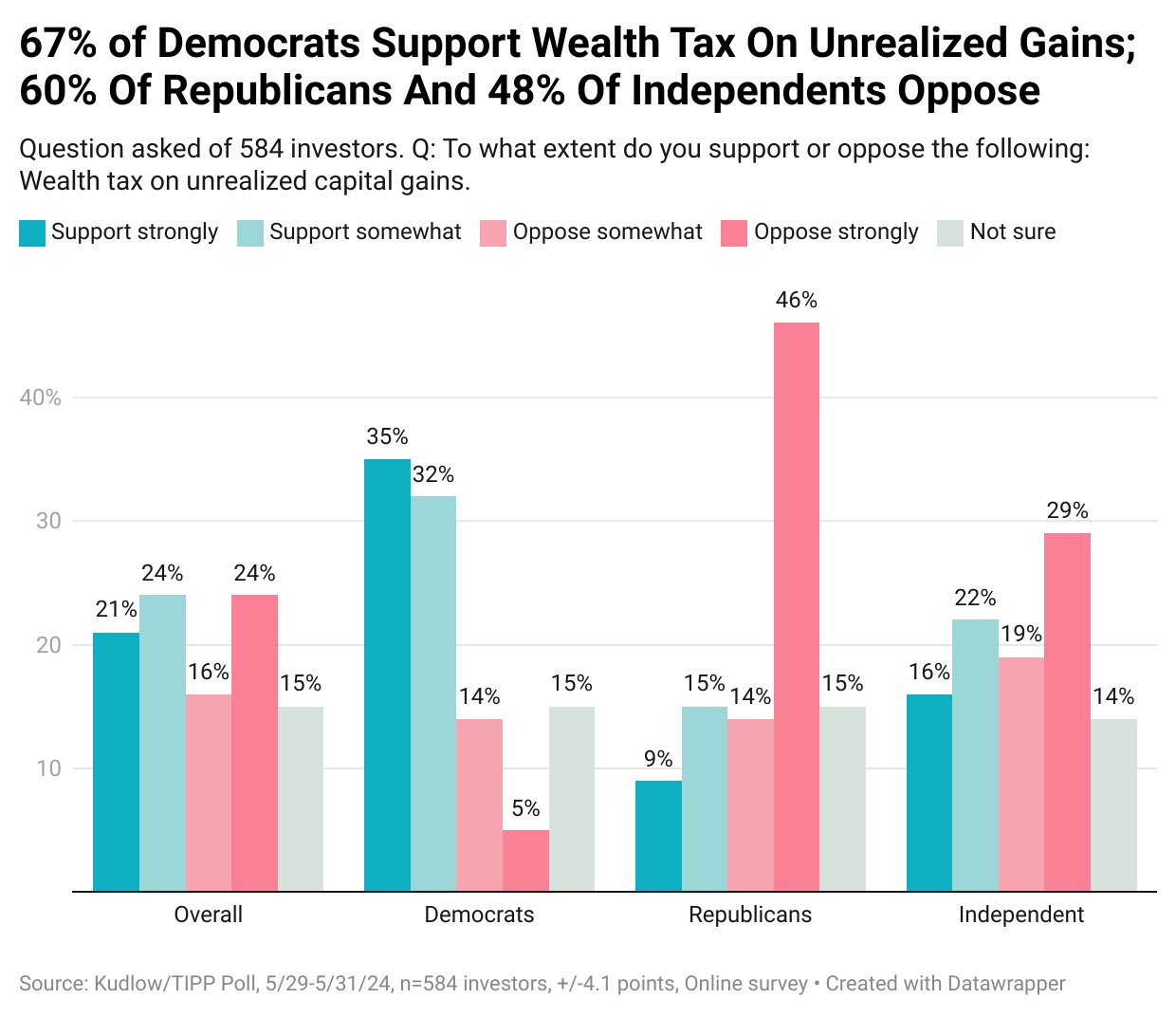

There is a divide in public opinion regarding the wealth tax on unrealized gains. A recent Kudlow/TIPP Poll in late May asked 584 investors: To what extent do you support or oppose a wealth tax on unrealized capital gains? Nearly one-half (45%) support the tax, and another 40% oppose it. The breakdown is as follows:

- 21% support strongly

- 24% support somewhat

- 16% oppose somewhat

- 24% oppose strongly

- 15% not sure

Digging deeper, 67% of Democrats support the idea, while 60% of Republicans and 48% of independents oppose it.

The government sucking money out of the economy to support its free-spending is simply a disastrous idea. Taxing unrealized capital gains has many downsides and discourages long-term investments. First, investors might face liquidity problems because they have to pay taxes on gains they haven't received in cash. This ill-conceived tax could force them to sell assets prematurely at unfavorable times, making long-term investments less attractive.

Additionally, the complexity and uncertainty of valuing assets every year can be a hassle and further discourage investment. Investors could opt for short-term gains or other tax-advantaged assets, which could hurt funding for startups and innovative projects.

Third, the economy would experience a capital flight, with high-net-worth individuals and businesses moving their money to places with more favorable tax treatments.

The tax could also negatively affect retirement accounts and long-term savings plans, which often include investments that grow over time, diminishing their value and impacting retirement security.

In summary, the unrealized capital gains tax may decrease economic investment, thereby impacting growth and job creation. Overall, the tax is a bad idea devised by progressive politicians who have no clue what it means to run a business. It threatens to stifle investment and drive capital away from our economy.