By Anas Alhajji, Project Syndicate | January 16, 2026

Some analysts have suggested that Donald Trump seized control of Venezuela’s oil reserves to boost profits for US refineries or to lower energy prices for American consumers by flooding the global market with crude. But this resource grab is most likely motivated by greed, as well as the desire to curb China’s access to energy.

DALLAS – Nearly two weeks after US special forces invaded Venezuela to capture and extract Nicolás Maduro, many people believe that President Donald Trump was motivated to act by a desire to control the country’s vast oil reserves. But to what end? Does Trump want to boost profits for the US Gulf Coast refineries equipped to process Venezuela’s heavy crude? Or is the aim to flood the global market, lower oil prices for American consumers, and, as a bonus, break up OPEC?

Whatever the goal of commandeering Venezuela’s oil, achieving it depends on whether the country can significantly increase output.

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves, at an estimated 300 billion barrels, and has long been at the center of global energy geopolitics. Its heavy crude, especially from the Orinoco Belt, has historically played a critical role in supplying refineries optimized for such feedstock, including those along the US Gulf Coast. As a result, many US administrations have regarded Venezuela as a strategic interest.

But after Hugo Chávez, Maduro’s predecessor, began a second wave of nationalization in 2007, seizing hundreds of private businesses and foreign-owned assets in Venezuela, the US came to rely more on crude from Canada – a politically stable ally. These long-life, low-decline reserves arrive through an intricate web of pipelines and are sold at a discount. Last year, the US imported an average of 6.2 million barrels per day of crude (mostly medium and heavy sour), of which more than 60% came from Canada.

By contrast, US refineries did not import any Venezuelan crude in the first few months of 2025, and started buying small amounts only after the Trump administration allowed Chevron to re-enter Venezuela for oil production and export under relatively strict conditions. Before Maduro’s arrest, US refiners imported only about 150,000 barrels per day from Venezuela.

Moreover, Trump has announced that the 30-50 million barrels of sanctioned oil that Venezuela will “turn over” to the US will be sold on Venezuela’s behalf, with the administration controlling how the proceeds are spent. Two trading houses are already in talks about selling this oil to Chinese and Indian refiners. Taken together, these realities demonstrate that Trump is not looking to satisfy Gulf Coast refineries’ thirst.

Some have speculated that Trump may use Venezuelan crude to fill the US strategic petroleum reserves. But it has become an unwritten rule since the 1990s that only domestic oil will be used for this purpose – a policy from which Trump is unlikely to deviate, not least because Venezuelan crude is too sour to meet the specifications required for SPR purchases.

Instead, based on Trump’s comments and actions, he seems to be after money. Venezuela agreed to compensate US oil companies for their nationalized assets, but did not pay, even after these firms went to arbitration and won their cases. Trump wants to collect that money, but Venezuela is bankrupt, and oil is its most valuable resource.

These moves belie the claims that Trump is pursuing lower oil prices and taking aim at OPEC. Why would energy companies spend tens of billions of dollars reviving Venezuela’s dilapidated oil industry, which is what Trump is asking of them, only to slash their own profits by flooding the market with crude and driving down prices?

In any case, Venezuela will not be able to increase production meaningfully any time soon. To increase production by one million barrels per day requires roughly $20 billion in investment and will take about three years. By that point, some forecasters project that global oil demand will have grown between 2-3 million barrels per day, while depletion will have reduced production by 12-15 million barrels per day, meaning that the world will need around 15 million barrels per day of new oil. Thus, any increase in Venezuelan production will not flood the market, nor will it lower prices. In fact, it would be a welcome addition to global supplies.

As for where this $20 billion will come from, history suggests that most of it will be redirected from future projects in other countries, rather than additional spending above these firms’ annual investment budget. The effects of increasing production in Venezuela will therefore be limited because it comes at the expense of increased production elsewhere in the world. The idea that such a shift would cause problems within OPEC is absurd.

The oil, and the money it brings in, are clearly driving Trump’s interest in Venezuela. But broader political issues are also at play. In recent years, Venezuela has developed deep economic ties with China, which purchased most of its sanctioned oil. As the economic rivalry between China and the US intensifies, particularly in the race for AI dominance, reliable access to abundant energy while controlling energy flow to competitors will be indispensable.

Anas Alhajji is an energy economist and the former chief economist at NGP Energy Capital Management.

Copyright Project Syndicate

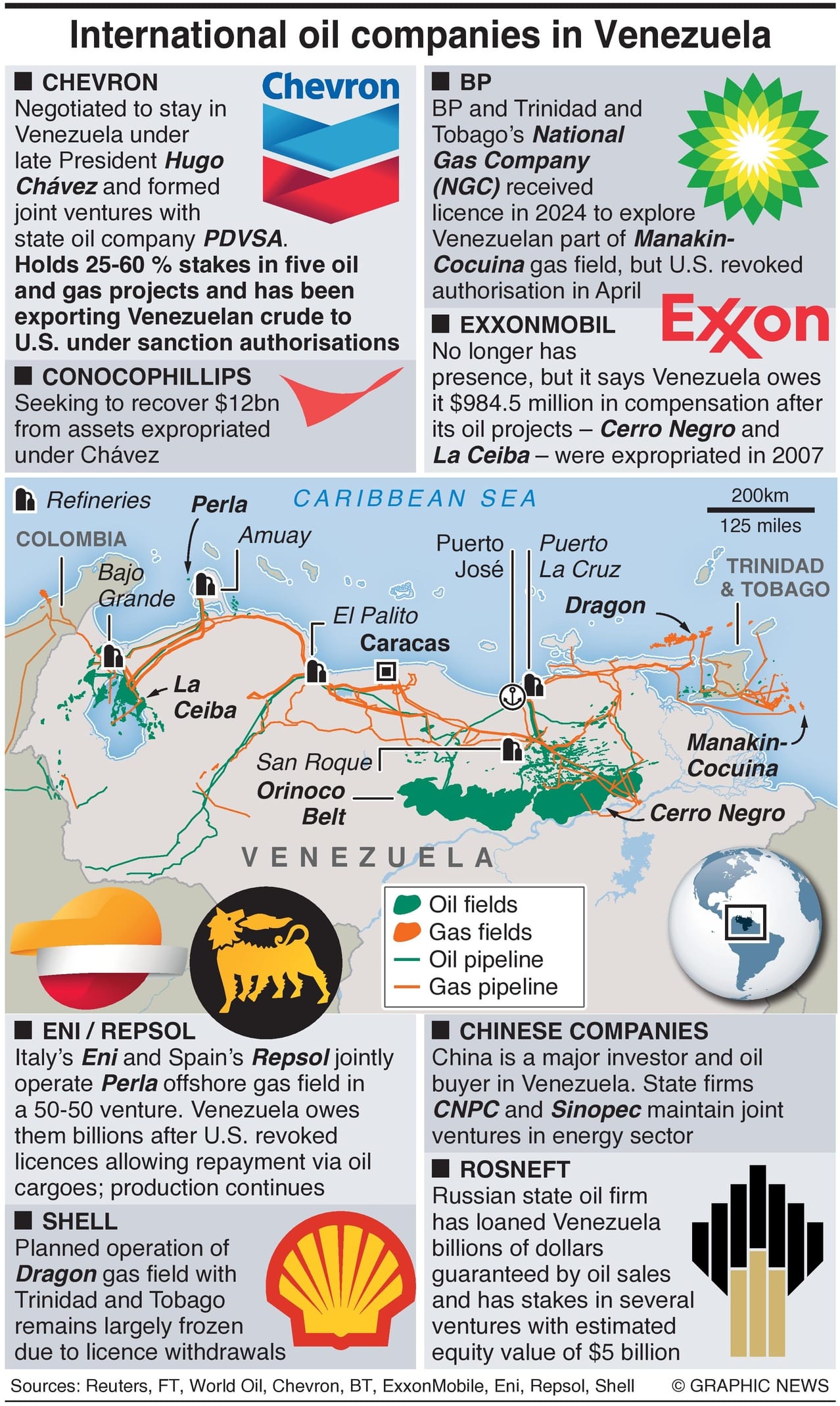

International Oil Companies In Venezuela In Focus

International oil companies in Venezuela are in the spotlight amid Washington’s push to exert influence over the country’s vast oil sector following the U.S. capture of President Nicolás Maduro.

U.S. President Donald Trump announced that Venezuela’s interim authorities will transfer between 30 million and 50 million barrels of sanctioned crude to the U.S., to be sold at market prices with the proceeds managed by the U.S. government.

The deal, potentially worth up to $3 billion, marks a significant escalation in U.S. involvement in Venezuela’s oil industry. It comes as part of a broader strategy to “free up” blocked Venezuelan oil flows after Washington imposed a blockade that had left millions of barrels of crude stranded in storage.

Analysts warn that Venezuela’s oil production could face further disruption if storage shortages continue, underscoring the fragile state of the country’s energy sector. Critics of the U.S. approach say the policy risks deepening geopolitical tensions and amounts to exerting undue pressure on Caracas to grant access to its oil reserves.

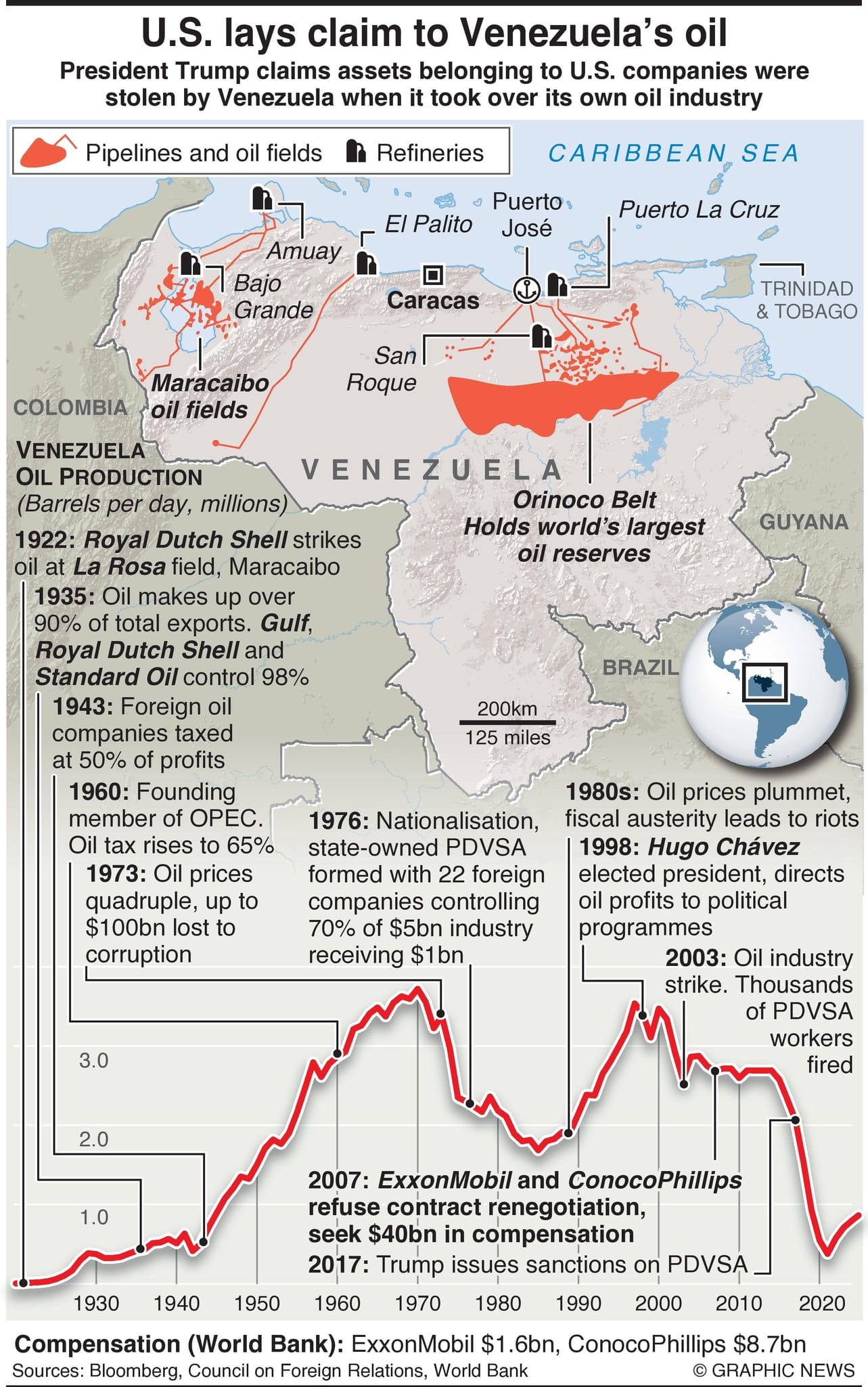

U.S. Lays Claim To Venezuelan Oil Assets

President Trump claims assets belonging to U.S. companies were stolen by Venezuela when it nationalized its oil industry in 1976, and a renegotiation of contracts in 2007.

The 22 foreign oil companies, which controlled about 70% of the $5 billion Venezuelan oil industry at the time, received $1 billion in 1977. When Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez wanted to renegotiate contracts with foreign oil companies, Chevron agreed to the new terms, but ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips refused, seeking $40 billion in compensation. The World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes awarded ExxonMobil $1.6bn, and $8.7 billion to ConocoPhillips.

Oil revenues have been central to Venezuela’s collapsing economy for almost a century, now accounting for about 88 percent of the nation’s roughly $24 billion in exports. But years of mismanagement, corruption, and the impact of U.S. sanctions have driven production sharply downward, deepening the country’s economic crisis and diminishing its ability to pay the compensation that is due.

editor-tippinsights@technometrica.com