At its core, the concept of the H-1B visa, first enacted by President George HW Bush in 1990, is simple. US employers occasionally face situations in which they can’t find competent Americans to fill open positions at their facilities.

Rather than let American commerce suffer and cause hardships to customers, current employees, and shareholders, the law allows companies to bring in qualified individuals from abroad to work in the United States temporarily. Those brought in must be paid prevailing wages, as “paid to other workers with similar qualifications and experience”.

In my 2013 book, The New H-1B/STEM Provisions: How the US Senate Continues to Undermine American Competitiveness, I critically examined the H-1B visa program and the proposed Immigration Innovation Act of 2013 (the I² bill). I argued that, despite good intentions, both the existing program and the proposed 2013 reforms fundamentally undermined American competitiveness in STEM fields.

First, foreign outsourcing companies—particularly Indian IT firms like Cognizant (American only in name), Infosys, and TCS—dominated H-1B visa applications, often displacing qualified American workers rather than supplementing the workforce with genuinely scarce talent. These companies had perfected strategies to game the system, treating H-1B visas as inventory to staff client projects rather than as a means to bring exceptional individuals into permanent positions.

Second, critical program terminology had been systematically misinterpreted or deliberately abused. Terms like “U.S. employers,” “qualified individuals,” “temporary work,” and “prevailing wages” had lost their intended meanings. What was designed as temporary employment for specialized talent had become a permanent staffing solution. “Prevailing wage” calculations routinely undervalued American workers’ market rates, creating artificial cost advantages for H-1B labor.

Third, the cumulative impact had been devastating for American STEM professionals. Rather than complementing the domestic workforce, the program had facilitated the outsourcing of millions of STEM jobs, eroding both the quality and competitiveness of the American workforce. Young Americans increasingly questioned the wisdom of pursuing STEM careers after seeing experienced professionals displaced by cheaper H-1B workers, who themselves felt trapped by their employers.

Today, the wait for H-1B workers from India to obtain a Green Card can take upwards of 80 years. More than 200,000 children of H-1B workers who age out of their parents’ application when they turn 21 must rejoin the H-1B line at the back of the queue.

It has been thirteen years since my book came out. I am pained to note that nearly every one of my predictions has come true.

Now, a working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, “The H‑1B Wage Gap, Visa Fees, and Employer Demand” by George J. Borjas (Working Paper 34793, February 2026), confirms many of the points I had anecdotally made in my book. [Professor Borjas is a Cuban-American economist and the Robert W. Scrivner Professor of Economics and Social Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School.] More on this paper later.

As I noted in my book, the 2013 Senate bill, which passed with a convincing 68-32 majority, contained extraordinary concessions, such as increasing the H-1B cap from 65,000 visas (which it is today, plus the 20,000 visas for those with advanced degrees) to 115,000, with escalators potentially reaching 300,000—nearly quintupling the current limit. The bill would have eliminated caps on advanced degree exemptions, allowed dual intent for international students, authorized employment for H-1B spouses, and exempted STEM advanced degree holders from Green Card caps.

I had worried that the massive increase in H-1B visas would risk oversaturating the STEM labor market, suppressing wages, and discouraging Americans from pursuing STEM careers. Why would a talented American student invest years in a difficult engineering degree when the resulting career offers diminished prospects due to systematic wage suppression?

Thanks to a sloppy executive order signed by President Obama, employment authorization for H-1B spouses, the H-4 EAD, became a reality in May 2015. Making the H-4 EAD open-ended without imposing tests on the local labor market or beneficiaries’ skills did not make sense.

While the primary visa holder must prove specialized skills through extensive documentation, their spouse can work in an identical role in the same company with zero skills verification. An employer who claims no qualified Americans exist for a specialized position can then hire the H-1B spouse for that same role without proving anything. This is a loophole that makes a mockery of the ‘specialized talent’ requirement.

Worse, international students could enroll in American graduate programs primarily to obtain immigration status rather than to pursue educational opportunities. Such a move would transform universities into immigration processing centers by offering diploma mills and dilute the vaunted quality of American graduate programs. This phenomenon is already common. Numerous inferior graduate programs exist around the country, turning out graduate students desperate to gain employment at any wage. Many students routinely violate the terms of their student visas by working in ethnic stores and restaurants to earn cash.

In the book, I had hoped that the Senate provisions of the I² bill would somehow die because a 400% increase in H-1B visas was not sustainable. This is exactly what happened. The Republican-led House of Representatives ruled out voting on the Senate bill, and the bill died.

It is shocking that, despite the bill dying and most of its provisions dying with it (except the H-4 EAD), America’s employment market has suffered serious consequences. In my consulting practice, I have families who complain that their American-born children are unable to find internships or jobs and cannot compete with H-1B and STEM OPT workers, who are willing to work for far less in indentured employment simply because they want to settle down in the United States.

Now, Professor Borjas’s paper provides strong evidence that H‑1B workers indeed earn substantially less than comparable US workers. After controlling for full skill and location characteristics, the preferred estimate shows H‑1B workers earn 16% less than comparable natives. In dollar terms, the adjusted gap is roughly $25,000–$31,000 annually.

The findings have major implications for immigration policy, labor markets, and the design of high‑skill visa programs.

The paper also documents large firm‑level differences. For example, average H‑1B salaries exceed $150,000 at firms like Meta and Apple but are closer to $80,000 at outsourcing firms such as Infosys and Wipro.

Several factors may explain the wage gap:

- Reduced mobility: H‑1B workers face frictions when switching employers, giving firms enormous power. Annual separation rates for H‑1Bs are around 9.4%, far below the 20–25% typical for comparable US workers.

- Occupational clustering: H‑1Bs are heavily concentrated in high‑tech occupations and high‑cost metro areas, which distorts raw wage comparisons.

- Skill differences: H‑1Bs are younger and more likely to hold master’s degrees, but these characteristics do not eliminate the wage disadvantage once properly controlled.

Prof. Borjas’s wage gap model merges three major datasets: Labor Condition Applications (LCAs), I‑129 petitions filed by employers after winning the H‑1B lottery, and the American Community Survey (ACS). The analysis focuses on H‑1B workers hired by for‑profit firms under the 85,000‑visa annual cap.

As I did in my book, Prof. Borjas maintains that high‑skilled immigration programs, when implemented correctly, generate economic benefits for receiving countries, both through higher tax contributions and productivity spillovers. Demand for H‑1B visas far exceeds supply: between 2021 and 2026, roughly 450,000 workers competed annually for 85,000 slots, leading to a lottery system.

Because H‑1B workers earn substantially less than comparable natives, firms enjoy large payroll savings—nearly $100,000 over a six‑year term. This suggests that firms might be willing to pay a significant fee to secure a visa.

Using a labor‑demand model, the paper simulates how different fee levels would affect employer hiring decisions. The key finding is that such fees would have little or no impact on the number of H‑1B workers hired, because demand is highly inelastic. The higher fees would shift the composition of H‑1B workers toward more skilled applicants, as only higher‑productivity matches justify the cost. The new lottery rules, which favor higher-wage earners, also move the visas toward the “best and brightest” model of the original H-1B legislation.

As an immigrant from India, I have been in the United States for nearly 40 years. When I first began working in New Jersey on an optional training program after earning a Master’s degree in Computer-Aided Manufacturing with a published thesis on robotics assembly, the H-1B program did not even exist.

For critics who say I am conveniently finding fault with the H-1B program after I obtained my Green Card, my response is that I was lucky to be a beneficiary of a new government program (for which I am forever grateful) that invited people with specialized skills to immigrate to America. My regret in writing my 2013 book and today is that that promise is no longer assured. Fraud and abuse have wrecked the H-1B program.

My employer had interviewed over 100 local candidates before he hired me to develop Computer Numerical Controlled programs for four Yamazaki Mazak machining centers that were to be delivered two months after my hire date. A few weeks after I was hired, I flew to Cincinnati to train at Mazak’s training center. Six years later, as an MBA student at Carnegie Mellon University, I traveled to Japan on a Japan-USA scholarship and visited the main Mazak plant in Nagoya and the nearby Toyota factory.

The new machines would replace 20+ machines, some dating back to World War II. When the company hired me, it was concerned that the machines would ship soon, but it had not yet hired an engineer to program them. My employer was so eager to have me commit to his company for the duration of the program conversion that he retained (and paid for) his personal immigration attorney, who was doing paperwork for his immigrant wife, to push through my Green Card application.

In a way, I was an agent of change, helping the company secure a major contract with the Department of Defense to supply precision bearings to the military during the buildup to the first Gulf War in 1991. The key selling point was the company’s plans to switch production to four state-of-the-art machining centers, enabling extremely precise tolerances. These tolerances were out of reach of the old machines.

On the flip side, the switch led to some reclassification among the shop-floor workers who had operated those old machines for decades. Luckily, the defense contract was so large that I displaced no one, as those workers were absorbed into other roles within the company.

The H-1B visa should be reformed to ensure a net addition to America. This was the intent of the original program signed into law by President Bush 41.

Rajkamal Rao has been a TIPP Insights columnist and member of the Editorial Board for over four years. He also publishes on Substack, with all of his work available for free. Readers may subscribe to get new articles sent straight to their inbox.

👉 Show & Tell 🔥 The Signals

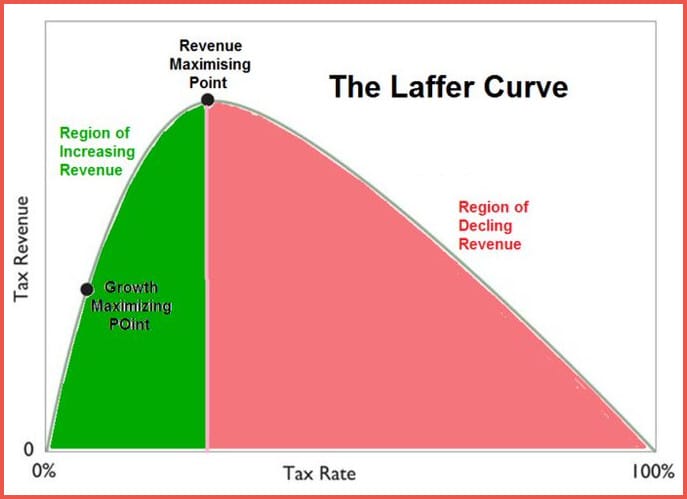

I. The Laffer Curve Explained

The Laffer Curve is a simple idea about how tax rates affect how much money governments actually collect.

Think of it this way:

- If the tax rate were 0%, the government would collect no taxes.

- But if the tax rate were 100%, people would have little reason to work, invest, or report income — because everything they earn would go to taxes. Revenue would again fall very low.

So somewhere between 0% and 100%, there must be a tax rate that brings in the most revenue. That relationship forms the curved shape shown above.

Why higher taxes don’t always mean higher revenue

At moderate tax rates, people continue working and investing, so raising taxes can increase government revenue.

But if taxes get too high, people may:

- Work less,

- Delay investments,

- Move money or businesses elsewhere,

- Or legally shift income to reduce taxes.

When that happens, the tax base shrinks, and total revenue can actually fall even though tax rates are higher.

Why economists still argue about it

Most economists agree the curve exists in theory.

The big disagreement is:

Where is the peak?

Are current tax rates below it, near it, or above it? The answer varies by country, time period, and type of tax.

Bottom line

The Laffer Curve doesn’t say all tax cuts raise revenue or all tax hikes hurt revenue. It simply says:

There is a point where taxes become high enough to discourage economic activity and reduce total collections.

And debates over tax policy usually center on where that point lies today.

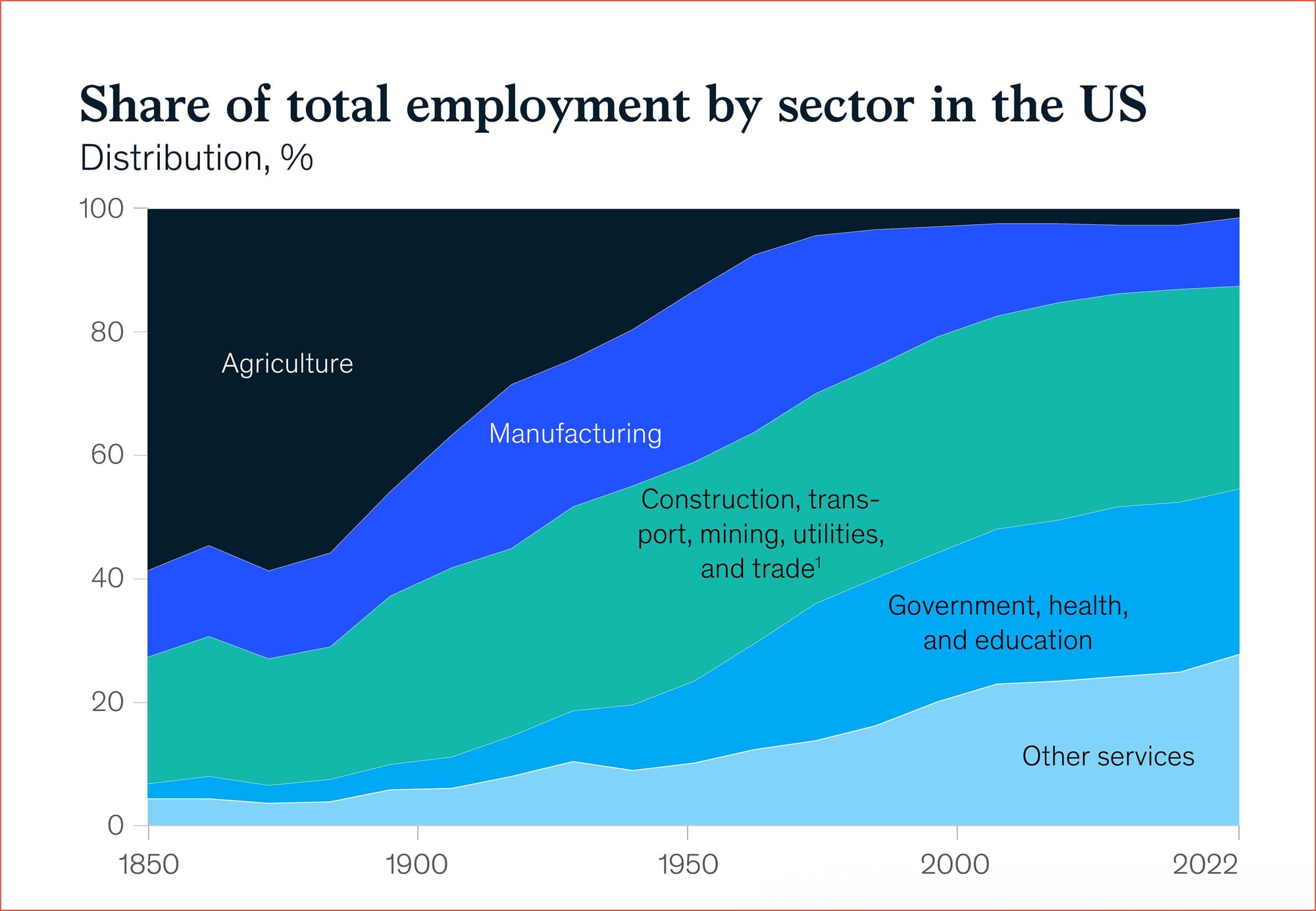

II. From Farms to Services: A Century Shift

McKinsey data show one of history’s biggest economic shifts: in 1925 most workers farmed; today only a small fraction do. Productivity gains moved labor into manufacturing and now overwhelmingly into services — reshaping cities, incomes, and politics.

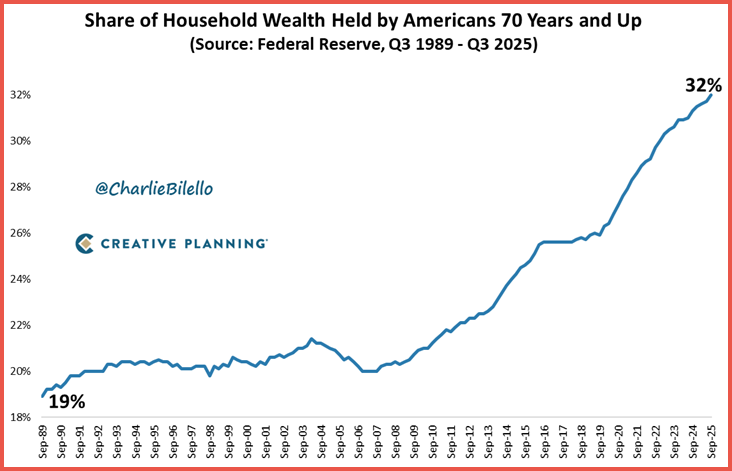

III. Americans 70+ Hold Record Share of Wealth

Federal Reserve data shows Americans aged 70 and older now hold 32% of total household wealth — a record share. Longer lifespans, asset appreciation, and demographic aging are concentrating wealth among retirees even as younger households struggle with housing and debt burdens.

editor-tippinsights@technometrica.com