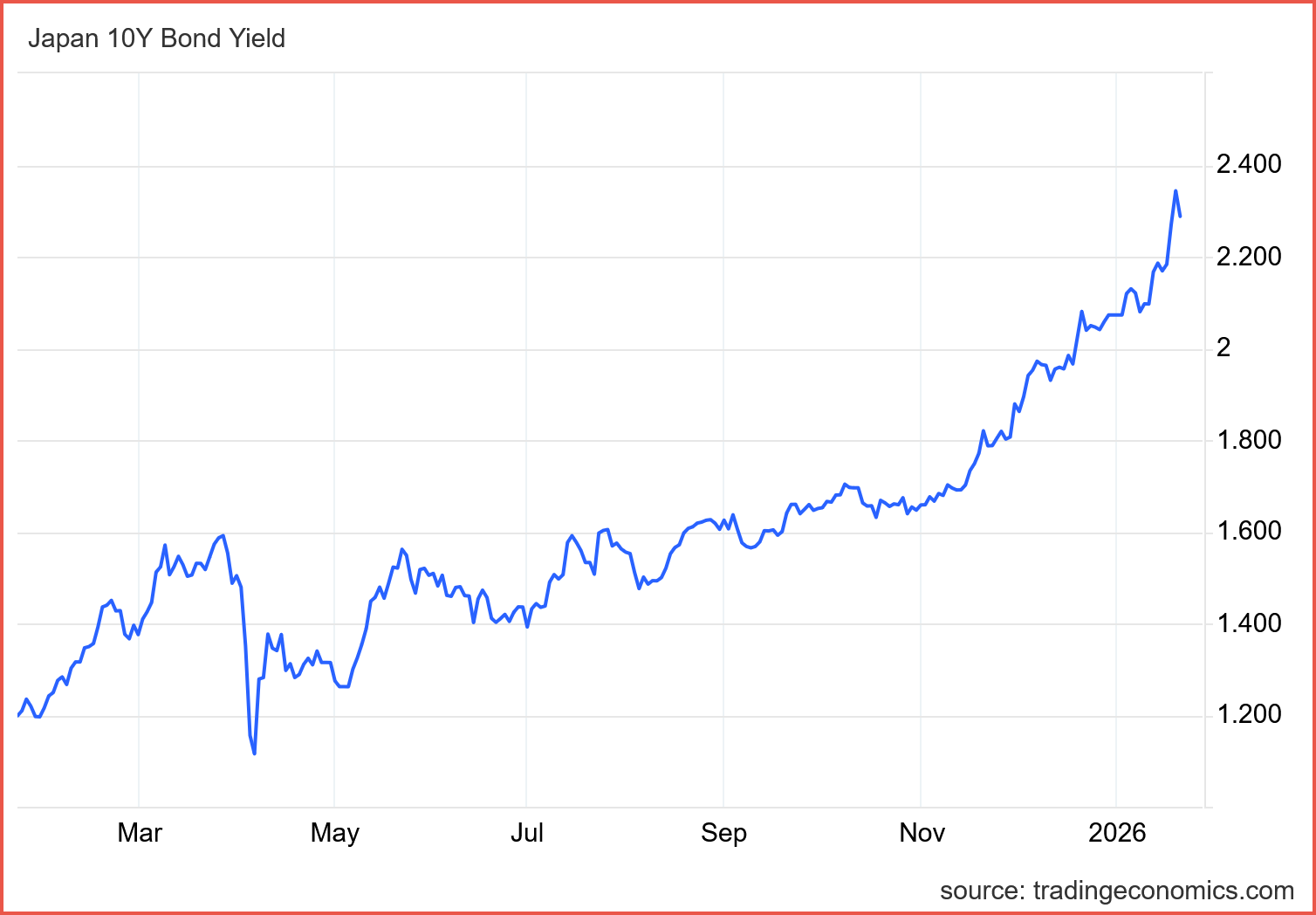

On Tuesday, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, speaking from Davos on War Room, said that the recent stock market volatility came from large moves in the Japanese bond market and not from tariff talk about Greenland. He even described the Japanese swings as a “six standard deviations” event, the kind of rare jolt that can ripple through global markets.

That surprised many people. Japan’s bond market is usually dull. It is enormous, tightly managed, and famously calm. For decades, it barely moved. Investors treated it as background scenery rather than a source of risk.

The reason was simple. Japan has very high government debt, more than twice the size of its entire economy, but interest rates stayed close to zero for years. As long as borrowing remained cheap, the debt did not seem threatening. Most people assumed the system was stable.

That assumption is now being questioned.

What has changed is the price of that debt.

To put the recent move in perspective, let’s look at what has been happening in the bond market. Japan’s 10-year government bond yield spent much of the past decade near zero. Even last year, it was around 1 percent. This week, it rose above 2 percent. The change has been even sharper for longer bonds. Yields on 30-year bonds have climbed toward 4 percent, while 40-year bonds have moved above 4 percent, levels rarely seen in Japan’s modern bond market. For a system built on stability, those are significant moves in a short period.

When interest rates rise, bond prices fall. Here is a simple example to illustrate how it works. Imagine you own a house worth $120,000 and you rent it out for $6,000 a year. Your yield is 5 percent. Now suppose the housing market dips and your house's value falls to $100,000, while the rent stays at $6,000. Your yield has risen to 6 percent. If the house price climbs to $150,000, the same rent now yields just 4 percent. The rent did not change, but your return did.

That is exactly how bonds work. The interest payment stays the same, but the yield changes because the bond’s price changes. If the price falls, the yield rises. If the price rises, the yield falls.

Investors now demand higher returns before they are willing to lend to Japan for very long periods, reflecting growing caution.

For many years, the Bank of Japan played a central role in keeping the bond market quiet. It bought large amounts of government debt to hold down interest rates and reduce volatility. That approach worked when inflation was barely visible and creating money carried few obvious costs. However, those conditions have changed.

Inflation has returned, even if it remains modest. The central bank has raised rates and no longer signals a willingness to buy unlimited government debt indefinitely. Consequently, investors have adjusted their expectations.

Politics has added another layer. A snap election and promises of tax relief and higher spending indicate heavier government borrowing ahead. That raises a basic question every bond market eventually asks: Who will buy all this new debt, and at what interest rate?

That question hits hardest at the long end of the market. Lending for 30 or 40 years requires confidence not only in today’s policies, but in decades of future decisions. When that confidence weakens, lenders demand higher returns.

Another reason Japan matters is the carry trade. For years, investors borrowed cheaply in Japan and invested elsewhere for higher returns. The strategy worked as long as Japanese interest rates stayed very low and the yen remained weak. Tokyo became the world’s cheapest source of funding.

Rising rates make that trade less attractive. Borrowing in Japan is no longer almost free. As yields climb, some investors unwind those positions by selling assets abroad and bringing money back home. When that happens at scale, it can push interest rates higher in other countries and increase market volatility.

This helps explain why developments in Japan can affect markets far beyond its borders. For years, Tokyo’s low rates helped keep borrowing cheap around the world. A shift in that dynamic forces investors to rethink assumptions that once felt safe.

This does not mean Japan is facing a financial breakdown. The country still has deep domestic savings and strong institutions. Its central bank retains powerful tools. What is happening instead is a reassessment after a long period of calm.

The lesson from Japan also matters closer to home. The United States carries a national debt of roughly $38.5 trillion. In the years ahead, a large share of that debt will need to be refinanced. Bonds issued when interest rates were very low will be replaced with new borrowing at much higher rates.

That process does not cause a crisis overnight. But it does make debt more expensive, budgets tighter, and tradeoffs harder to ignore.

The lesson from Japan is straightforward. Borrowing can feel painless for a long time, especially when central banks help keep costs down. But debt is never truly free. Eventually, lenders want to be compensated for the risk they undertake.

Japan’s bond market is sending a quiet signal. When even the calmest markets do that, it is worth paying attention.

👉 Quick Reads

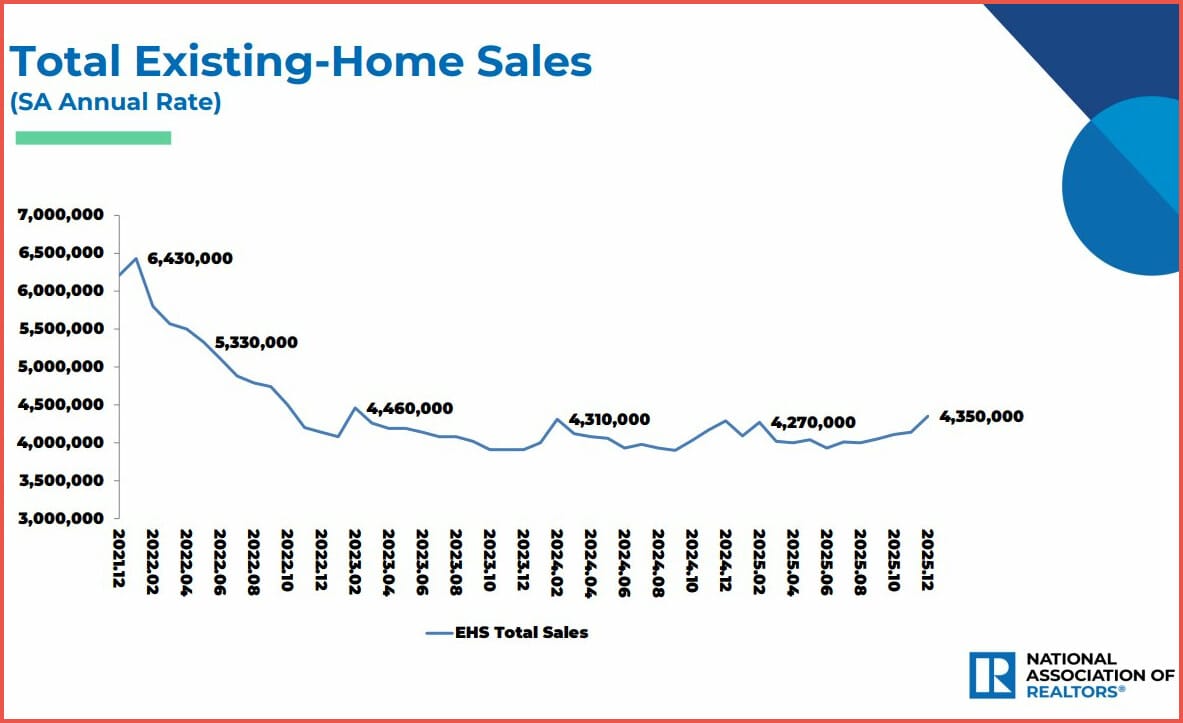

I. Home Sales Are Off the Bottom—But Still Far From Normal

Existing-home sales in December were the strongest in nearly three years, helped by slightly lower mortgage rates. Even so, sales remain well below pre-2022 levels, suggesting the housing market is stabilizing—not rebounding.

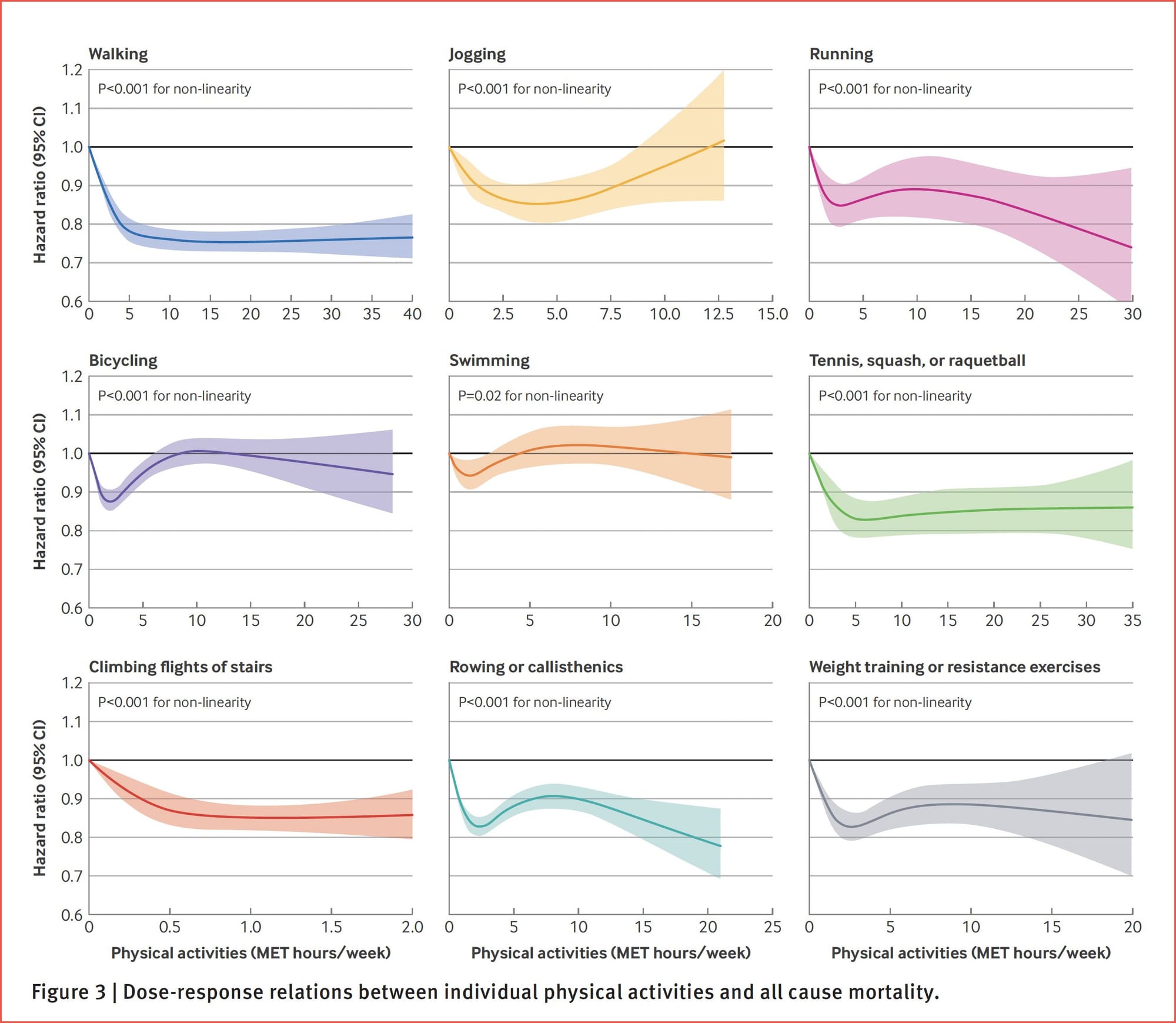

II. A Little Exercise Goes A Long Way

The biggest health payoff comes from going from no exercise to some exercise. Walking, light jogging, cycling, swimming, or lifting weights just a few hours a week sharply lowers the risk of early death. Doing more still helps, but the gains are much smaller. You don’t need extreme workouts—regular, moderate activity delivers most of the benefit.

How to read this chart

The x-axis shows how much exercise people do, from none on the left to more on the right. The y-axis shows the risk of early death, with lower lines meaning lower risk.

The lines show how the risk of early death changes as exercise increases. The steep drop at the start means going from no exercise to a little exercise brings the biggest benefit. After that, the lines flatten, showing that doing more and more adds only small extra gains. In short: most of the benefit comes early.

Example (walking)

Someone who goes from not walking at all to walking a few hours a week sees a large drop in risk. If that same person doubles or triples their walking time, the risk still falls—but only a little more. Most of the benefit comes from starting to walk, not from walking a lot.

📊 Market Mood — Wednesday, January 21, 2026

🟩 Futures Rebound After Tariff Shock

U.S. futures edge higher after Tuesday’s sharp selloff, as investors cautiously step back in while weighing unresolved trade and geopolitical risks.

🟧 All Eyes on Trump at Davos

Markets await President Trump’s Davos address for clues on Greenland, tariffs, and his broader second-term economic agenda, with Europe bracing for escalation.

🟦 Netflix Earnings: Growth, But at a Cost

Netflix delivers strong Q4 results but offers conservative guidance as acquisition costs rise amid its aggressive bid for Warner Bros. Discovery.

🟨 Berkshire Signals Portfolio Shift

A filing shows Berkshire Hathaway may exit its Kraft Heinz stake, marking a potential first major move under incoming CEO Greg Abel.

🟥 Gold Soars Past $4,800

Gold surges to fresh record highs as trade tensions and geopolitical uncertainty fuel a rush into safe havens, while oil slips on growth concerns.

🗓️ Key Economic Events — Wednesday, January 21, 2026

🟨 08:30 ET (USD): Donald Trump speaks — Markets may react to comments on the economy, trade, taxes, or foreign policy. Volatility often picks up during and shortly after remarks.

editor-tippinsights@technometrica.com