Last week, WeWork filed for bankruptcy and shook the Commercial Real Estate (CRE) sector at its seams. The company revolutionized the industry in 2010 with a simple business model: Lease office spaces from landlords at discounted rents, then beautify the areas up with ergonomically designed workstations and re-rent them to customers on a permanent or temporary basis at a markup.

We warned our readers eight months ago in our editorial about the impending crisis in the industry: Commercial Real Estate Struggles As Work-From-Home And High-Interest Rates Take A Toll

The commercial real estate industry - offices, industrial, retail (malls), and multifamily housing (apartments) - is facing two unprecedented structural challenges, both of which show no signs of easing. WeWork is a symptom of these challenges.

Covid. First, when Covid attacked with a vengeance, the CRE sector took a direct hit. Lockdowns meant that staff worked from home. The allure of downtowns fell as workers stopped visiting restaurants and eateries they had often flocked to during lunch and after work.

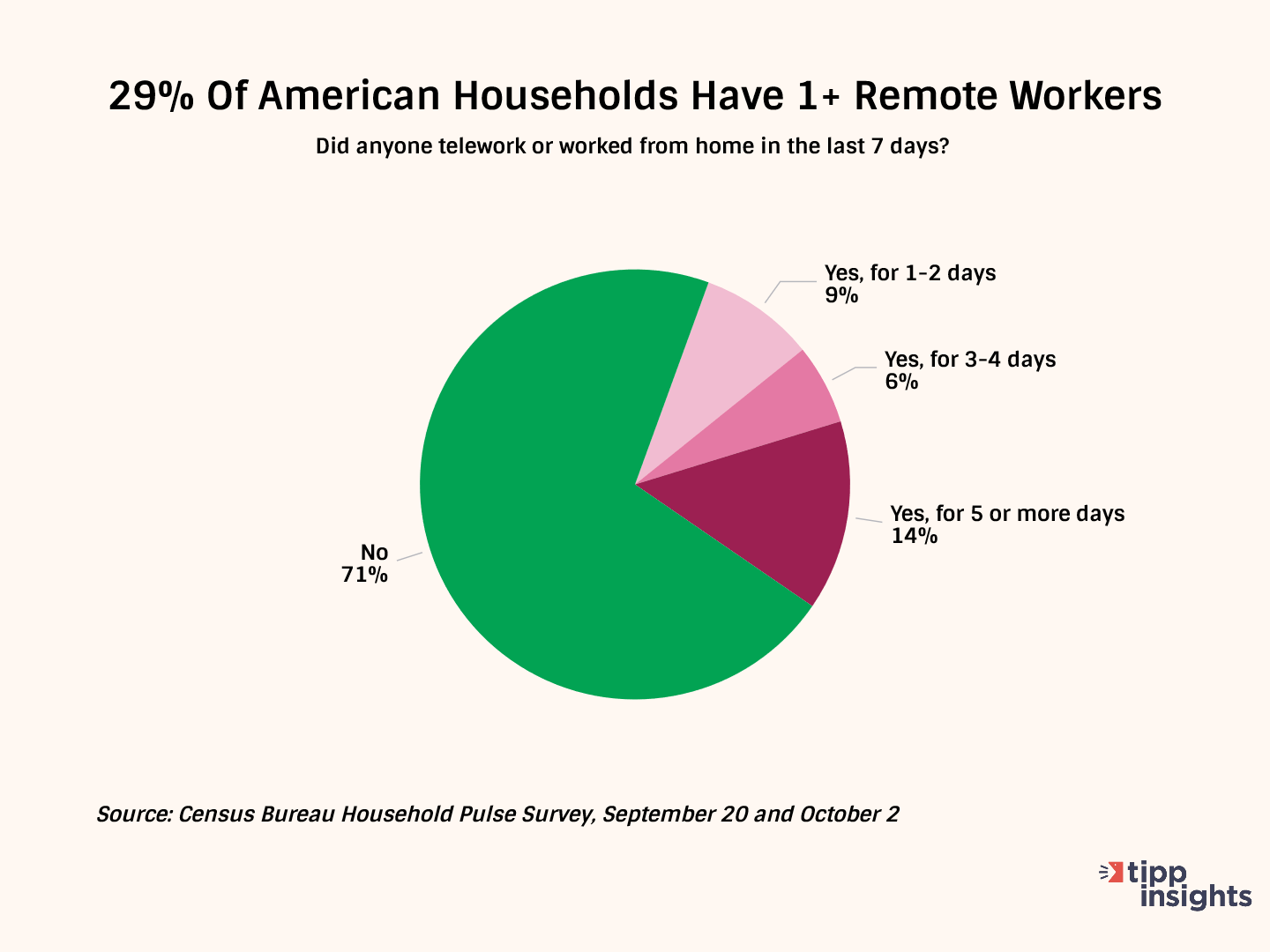

As Covid eased, companies perfected the hybrid model, with most employees working from home a few days a week. Companies began resorting to the so-called "hoteling" system. If employees wanted to work in the office, they had to "reserve" a working space that would expire at the end of the day. According to the Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey, 29% of Americans reported at least one person in the household working remotely for at least one day a week between September 20 and October 2.

By rotating workers through the week, companies could slash real estate needs by 40% to 50% and return those spaces to landlords. Landlords, in turn, have been struggling to lease out empty spaces as there aren't as many takers. Empty offices mean no rental revenue, but landlords still have to make loan payments to banks.

Interest rate increases. Second, the Fed has been raising interest rates steadily, from near zero in April 2022 to more than 5.25%, and holding it steady at the latest FOMC meeting. When a landlord approaches his bank to refinance his loan, he must pay a significantly higher interest rate, upwards of 6%, compared to the 1% he did during the golden years. With the asset's underlying value having fallen, the bank also warns him that the collateral value of the building no longer covers the loan's value, so could the borrower cover the margin? That is, pay up the difference? From where does the landlord get the funds to do this?

WeWork's troubles significantly magnify the CRE sector's troubles because of WeWork's size. In the US and Canada alone, WeWork had leased 18 million square feet of office space at the end of 2022. In an August 8 SEC filing, WeWork said, "Our losses and negative cash flows from operating activities raise substantial doubt about our ability to continue as a going concern." With the bankruptcy, WeWork's unused leased spaces will be released to a market when no one wants to lease. Excess supply and low demand create highly unfavorable conditions, as every high school economics student knows.

These unfavorable conditions are already crippling several other real estate players. Yesterday's Wall Street Journal reported a shocking story about increasing foreclosures on mezzanine loans. Many real estate companies do not want to put down a large downpayment when they finance a building's acquisition and borrow that from a different lender (generally a rural bank or a hedge fund) - meaning they have two lenders servicing their debt.

When a building's asset value falls, borrowers stop making payments as their properties are "underwater," a hopeless situation millions of homeowners found themselves in during the 2008 financial crisis. That is when banks foreclose on properties and attempt to recover whatever equity in the building still remains.

A New York Times story two weeks ago illustrates the above situation with a real-world situation. A New York landlord took out a $77 million loan on a building worth $127 million, posting the value of the building as collateral. But confronted with no rental income as vacancies shot up to 90%, the landlord stopped making loan payments to his bank's servicer, which revalued the building at just $42 million. That servicer is now moving to foreclose the property. (The story did not indicate that a mezzanine loan was involved.)

Foreclosures are terrible for the real estate industry. Everyone loses, including the banks. According to Moody's Analytics, the total outstanding CRE debt market is $4.5 trillion. Banks account for 38.6% of this lending, nearly $1.7 trillion. If you're a rural or community bank, and you are forced to foreclose because your borrower defaulted, the bank could be at risk and may need a bailout.

It's a double whammy situation for the banks, which must also contend with "duration risk." As we noted in March, Silicon Valley Bank largely failed because it had large deposits of Treasury Securities that lost value when the Fed raised rates. Bond prices move in an opposite direction compared to interest rates.

You may ask, "Why are interest rates so high?" Well, elections have consequences, and you can trace many of the nation's problems back to President Biden's policies. Biden's spending fueled inflation, which peaked at 9.1% in June 2022. In an effort to control inflation, the Federal Reserve had to raise interest rates. However, while the Fed is increasing rates to combat inflation, Biden continues to boost spending, further stoking inflation. It's like Biden's policies are the wind fanning the flames while the Fed, acting as the firefighter, struggles to extinguish the fire. The end result is prolonged stagflation.

Due to these high interest rates, Americans are now paying 11.4% for used car loans and 7.8% for mortgages. Under Biden, for most Americans, buying a new car has become unaffordable, and owning a new home is an unattainable dream. Tell that to Janet Yellen, the modern-day Nero, who will tell you how well we are prospering because of Bidenomics.

It's not a good time to be in the CRE sector. As is often the case, troubles in this sector tend to trickle down to residential real estate and the overall banking sector. In April, Elon Musk warned of another Great Depression. We wonder if the country is ready for this.

We could use your help. Support our independent journalism with your paid subscription to keep our mission going.